The geopolitical question of the moment is: how important is it to humour Russian leader Vladimir Putin? The answer is: not very. Throw him a fish or two, because he’s running a bluff and you don’t want to humiliate him, but there’s no need to placate him with major concessions.

This question has become urgent because President Putin is demanding guarantees that Ukraine will never join NATO. He also wants the alliance to withdraw all the non-local troops and weapons it has deployed in countries that were not in NATO before 1997. And he is hinting that he might invade Ukraine if NATO does not comply.

‘Areas that were not in NATO before 1997’ is a lot of territory. It includes Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, all under Soviet rule before 1989, plus five other countries in the Balkans that were Communist-ruled but not under Soviet control: Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Albania and North Macedonia.

That’s more than one hundred million people, most of whom have unhappy memories of Russian rule and a lingering fear of Russian domination. That’s why they all joined NATO (and most of them joined the European Union too).

They will never let the Russians make them vulnerable again, and there is no reason for NATO to give in to Putin’s demands. The notion that Russia might actually invade Ukraine is frankly ridiculous.

Ukraine is a country the size of France with 43 million people. Its armed forces are less well equipped than Russia’s, but they have become considerably more professional during seven years of low-level fighting against Russian-backed separatists in the two south-eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Russia has slightly more than three times Ukraine’s population, much bigger armed forces and a lot more money (thanks to abundant oil and gas), but invading Ukraine would not be a stroll in the park. The Russians could certainly take the east, and maybe Kyiv, but conquering the west would be doubtful. And afterwards, Russian occupation troops would face a huge and long-lasting guerilla resistance.

Besides, the immediate consequence of an overt Russian invasion would be a trade embargo by all the NATO countries that would quickly bring the Russian economy to its knees. Moreover, the Russian people are definitely not up for that kind of adventure: Putin’s entire regime would be at risk of collapse.

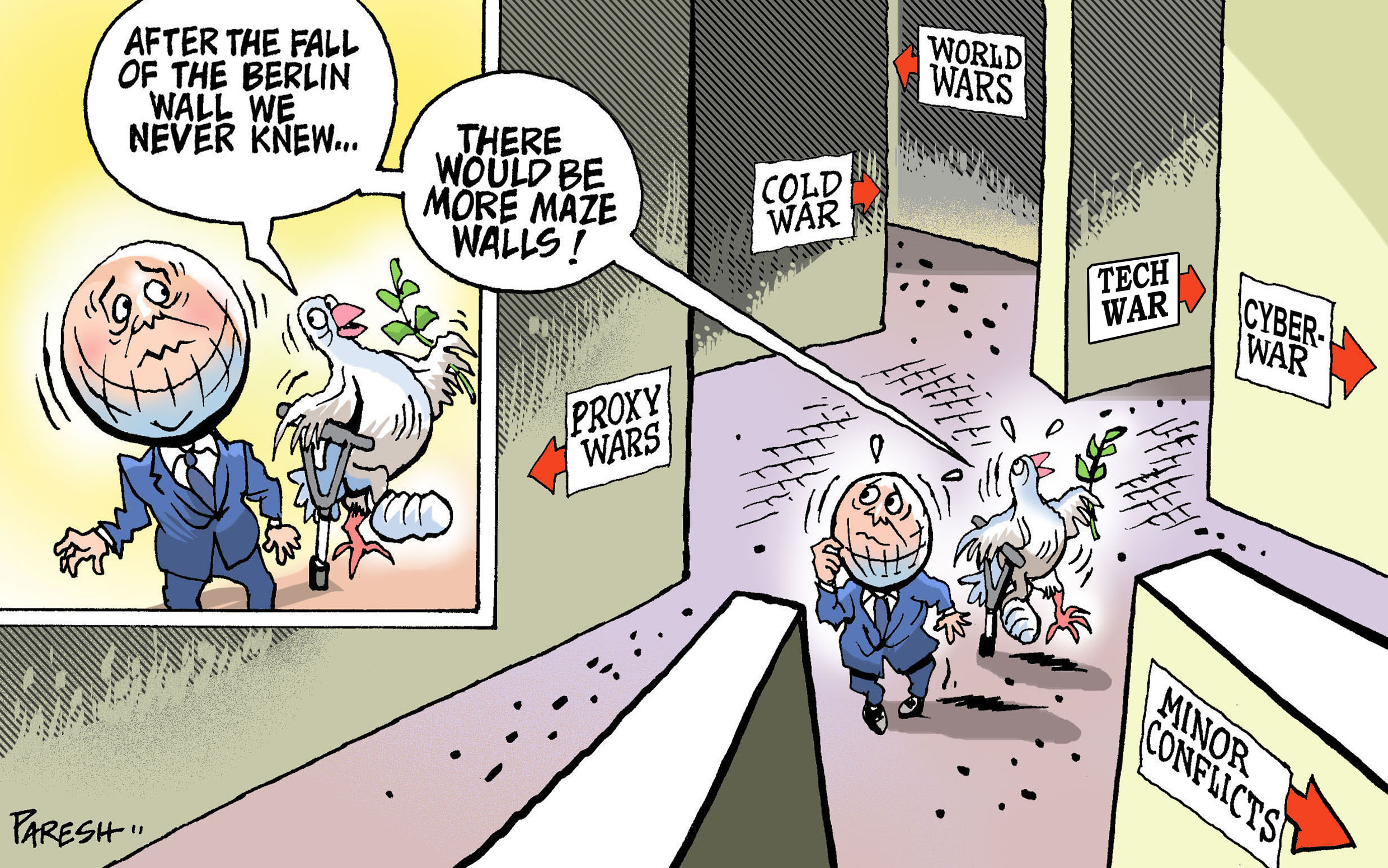

This is not like the old Cold War, when the Soviet Union and its satellites were only outnumbered two-to-one by NATO. Now it’s just a much diminished Russia against a greatly expanded NATO: three-to-one in regular military forces, seven-to-one in population, twenty-five-to-one in GDP.

Russia has lots of nuclear weapons, so nobody is going to attack it, but in any other kind of war it is hopelessly overmatched. Putin’s demands don’t really make sense in terms of Russian security.

Putin inherited the reality of an enlarged NATO when he took power at the end of 1999, and raised no objection then or for a long time afterwards. After all, he was very busy with the war in Chechnya and other post-imperial border conflicts for the next decade.

He did start obsessing over Ukraine after the 2014 revolution in Kyiv overthrew the pro-Russian president there, but he then effectively took Ukrainian NATO membership off the board by sponsoring a pro-Russian armed revolt in Donetsk and Luhansk.

There was never much support for Ukrainian membership in NATO anyway, precisely because it might oblige the alliance to defend Ukraine against Russia. By creating a permanent military confrontation in eastern Ukraine, Putin made Ukrainian membership unthinkable. The status quo was ugly but satisfactory – so why try to change it?

One possibility is that having Donald Trump in his pocket – nobody knows why, but he did – gave Putin a sense of security that has now evaporated. Another is that he just sees Joe Biden as weak, and he is trying his luck. But his motive doesn’t matter, really, because the whole project is foredoomed.

NATO doesn’t have to do anything except to make it clear to Moscow in private that any Russian aggression against Ukraine – not a full-scale invasion, which is out of the question, but even a border incursion somewhere – will be met with a full economic blockade of Russia.

Don’t say that in public, of course. Don’t back Putin into a corner, don’t make him lose face. Don’t create panic in the Western public with exaggerated reports of a Russian military build-up either (as the boys and girls at the Central Intelligence Agency in Washington have been doing simply out of habit).

Give Putin no concessions, but show him respect. Keep talking to him, and eventually he’ll come down from the ledge he’s gone out on at the moment.

Gwynne Dyer’s new book is ‘The Shortest History of War’.

Click here to change your cookie preferences