In a contender for the world title, THEO PANAYIDES meets a man looking for love who has found peace in poetry

Argyris Loizou sits in his small first-floor flat off the Larnaca-Dhekelia road, musing on life in general. “So in Cyprus, as you know, there’s like a timeline of what is the way to go. You get the job, you get married… and then you just perpetuate that life – which is fantastic, which is the life I wanted.

“All I wanted to do was get married, have my kids, come home, be a boring guy, and spend time with my wife and kids until they – y’know, put me in a home. That’s all I wanted. But that life wasn’t available.”

“Now 40 years old, and still no-one to love.

How can I be man enough

If all I can see is my shame and my disability?

So I fall, fall, fall.

I feel the full force of the fear of reality.

Forever trapped,

Forever alone,

Forever drowning in the cold harsh space of infinity.

I am a useless piece of shit

And the universe doesn’t give a fuck about me.”

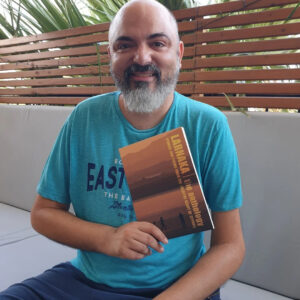

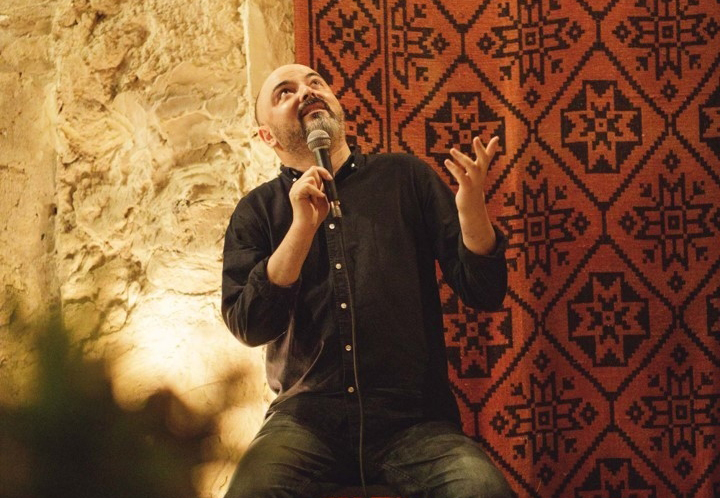

This is what Hollywood likes to call a cold open, usually followed by a freeze-frame and a cheeky narrator going ‘Yeah, that’s me. You’re probably wondering how I ended up here…’ – but who is Argyris, and how did he end up here? He’s in his 40s, as he says in the poem (he actually turned 43 on the 3rd of this month). He’s bald and bearded, sporting a ‘You’ll Never Slam Alone’ T-shirt and a deep expressive voice which comes in handy onstage. He was born in Manchester, grew up in Liverpool, and has lived in Larnaca since the age of 15. He also has muscular dystrophy, “specifically FSH which stands for facioscapulohumeral, which is face, shoulder and upper arms… It’s a degenerative condition. There’s no cure. There’s no therapy, other than physiotherapy”.

Argyris is the ‘pot-bellied penguin’ from the title of his poem – and I notice his loping, awkward walk straight away (like a penguin “trying to carry my baby chick between my legs,” as he says) but he doesn’t look especially pot-bellied, sitting opposite me as I sip a glass of water at a rather bare dining table. (He made some sourdough bread for the occasion, but it didn’t come out right.) “Well, I’m wearing black,” he points out with a rueful smile, then pats his abdomen: “There’s no muscle here, unfortunately, because of my condition, so it just comes out”. Certain muscles work, and others don’t – and of course his disease is degenerative, so muscles that worked in the past may suddenly atrophy. “It plateaus then goes down, plateaus then goes down,” he explains of his condition. “So it’s evil that way, because it doesn’t give you any warnings.” Argyris balls his hand into a fist, extends the arm, then lifts; he can do this with one arm but not the other, because only one has a working biceps. He crooks his elbow, bending the arm into an ‘L’ shape, then rocks it back and forth; he can do this with the other arm but not the first one, because only one has a working triceps. It’s mind-boggling.

That’s a typical bit, the way he’ll pause and check himself. He worries, more than once, about coming off pretentious, especially when he talks about his work. “I’m always scared of sounding like an idiot.” It’s also typical – and related – that the ‘constant battle’ he refers to was in his head, even though it was his body that had broken down. It’s no secret that mental strength and self-esteem make a difference in battling disability – and of course no-one can be totally calm and composed in the face of incurable illness – but Argyris’ temperament was especially volatile, with a kind of raw-wound sensitivity and a constant tendency to assume the worst. “My mind was always going round in circles,” he explains: “Why did you say that?’ ‘Why did you raise that eyebrow?’… Unless you tell me ‘Bravo’ I’m like ‘Oh, does he…? Or do they…?’”. He’s never wanted fame, per se. He certainly doesn’t want pity. He desperately wants connection, and approval. Above all, like the people in that Talking Heads song, he just wants someone to love.

Even before the muscular dystrophy diagnosis at 20, his life was fractious and difficult. Liverpool remains his “spiritual home”, Liverpool FC one of his passions – but he was horribly bullied at the all-boys school he attended there, both for having a foreign name and also, more generally, for being awkward and scrawny and shy. (He was the silent kid in the back, whom no other boy would sit next to.) Things got better when the family moved to Cyprus – “It was brilliant. American Academy Larnaca, everyone was great. There were girls!” – but “unfortunately later old habits came back, and I failed the sixth form twice,” he recalls. What old habits? His awkward mind going round in circles again, paralysed by the pressure of exams and the pressure of knowing that his parents worked so hard to send him to a good school – the family owned a fish-and-chip shop in the UK, then later a kiosk in Larnaca – and he couldn’t let them down. “Any pressure, anything, I would just close up, seize up. I call it my zombie brain!”

Speaking of pressure brings us to the slam poetry – an event, for the uninitiated, where poets perform three-minute slams before a live audience and a panel of judges – and the rather surprising information that everything is hard for him (even though he’s won the Cyprus National Slam twice now, most recently in 2021 with a Covid-themed piece called ‘A Meditation on the Shitshow’). Writing is hard, polishing and rewriting is hard, memorising the piece is hard – and performing is hardest of all, in fact it “terrifies me. Terrifies me! Every single time – and I host open mics, I perform regularly… All I want to do for five seconds before I perform is to throw up. That’s all I want to do”. Just the fact that he’s able to handle that pressure counts as a major feat – let alone that he’s used it to share his “emotional truth”, let alone that he’s won accolades for doing so.

Success came late, after years (it sounds harsh, but he says so himself) of failure. His condition came as a cosmic blow, a bolt from the blue; muscular dystrophy is usually hereditary but in his case it was just rotten luck, “a genetic mistake”. The diagnosis was followed by two operations in two years – his shoulders were “winged up to here,” he says, and had to be pulled back, surgically linked to his back which sparks constant pain – then came a decade of nothing in particular, working at the family kiosk and trying to pretend he was fine even while mired in loneliness and feeling “like lightning and LSD in my head,” as he puts it. “Trying to be normal so I can fake that I’m okay, and maybe you’ll like me, and maybe give me a hug – and maybe even marry me, for example.”

Strangely enough, the financial crisis of 2013 may be the best thing that ever happened to him – though at first it seemed like the opposite. His parents had to sell the kiosk and moved back to England for four years, leaving him even more alone (and unemployed) – but it also disrupted his routine, forcing him to change. He discovered meditation, which helped; he quit smoking, which also helped – then “I finally met somebody who actually tolerated me and my condition. It was a quick thing, she left – but she gave me that sense of ‘OK, aksizo’ [OK, I’m worth something],” he explains, lapsing into Greek. “Then, a month later, there was an open mic in Larnaca at the Tree of Life, and I thought okay, I’m going to write something there, and I did – and I won. And I’m like ‘Oh!’” (This was his first-ever slam, a political piece called ‘The Wonderful World of Sushi’; he wasn’t quite ready to talk about himself yet.) “And people going ‘That was good’ – what is this weird feeling?… And then it was open mics in Nicosia with WriteCy, with Max Sheridan and Marilena Zackheos; I have to mention their names, they’re so influential!” We’re now in about 2017, and the first-ever poetry slam in Cyprus – though winning was never his point, he says: “I just wanted my voice to be heard, and for people not to treat me like something in the background… I’m trying to get the audience to understand who I am as a person – and for that, I believe you have to show them your heart. You can’t bullshit them.”

It’s an interesting point about being treated like ‘something in the background’. One reason why Covid was weird for him, says Argyris, was the normalisation of the kind of life he’d endured for years, not just distancing – he talks in his latest piece about the “many steps back [people] take” when they hear about his condition – but also an acute sense of his own mortality. (Life expectancy is diminished by his illness.) I assume he’s familiar with rejection; people have been vile to him, and avoided him as if he were toxic – yet in fact his personality (and poetry) would be much less interesting if he were simply consumed by bitterness and what he calls ‘Woe is me’, a loathing of himself and others. In fact, it’s the opposite: for all his problems – and frequent intimations of melancholy – Argyris Loizou is absolutely bursting with love.

He loves his family: his parents and sister, his nephew and niece, his two godchildren. He loves Larnaca, “a special place”, and indeed he was involved in putting out an anthology last year, inviting 50 writers to share their experience of Larnaca and “elevate our little town a bit, because there’s a fantastic writing community here”. (Argyris’ own piece in the book is called Esso Mou, Cypriot for ‘At home’.) He loves everyone in that community, and is also part of an outfit called Pe’Ta which aims to encourage new writers, even if they don’t think of themselves as writers: “Standing up there, saying your truth – again, it sounds a bit pretentious – there’s healing in that”. He’s looking forward to Brussels in September, and inviting friends (and everyone else) to come along. “I’ve told people, I may or may not get married but I’m treating this like a bachelor party… If I win, we celebrate. If I lose, we celebrate.”

‘40 years old and still no-one to love’ says the pot-bellied penguin – but perhaps he’s discovered (or perhaps he’s always known) a more profound truth: the best way to find love is to put love out there yourself. His life remains quite volatile, with bouts of depression; in 2020, after the first lockdown, he shut himself in his flat for three months, refusing to answer the door or his phone. (He’s not sure what caused it; probably some sense of anti-climax after the weird solidarity of those first weeks.) Peace of mind remains elusive, but he’s getting there. “Let’s just say I’m not the best example of a – typical person. But I always try to be a better person.” The spirit is willing, even if the flesh is sometimes awkward.

Click here to change your cookie preferences