By Agnieszka Rakoczy

Singer, song writer, radio presenter, actor and editor, John Vickers has been here 50 years and worn many hats, but he still doesn’t like olives

July 18, 1972, a 22-year-old recent graduate from the French department of Leicester University is flying to Cyprus to marry his Cypriot girlfriend. On the plane, seated next to him, is a man with orange hair, his fingernails painted in “a nice shade of brown”.

“He was the first man I had ever seen with painted fingernails,” John Vickers, the well-known Cypriot journalist, recalls 50 years later.

Asked if he knew straight away who his fellow passenger was, Vickers laughs.

He admits sheepishly that he didn’t so much as even say “Hello Mr Bowie”, such was his upbringing and style. “I have always felt one should respect people’s privacy so I didn’t talk to him at all.”

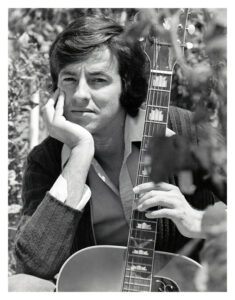

We are in the Vickers’ house in Larnaca, sitting in John’s study. Its walls are covered, floor to ceiling, with shelves full of CDs. Three guitars (John says he actually has more, in addition to a mandolin and a ukulele), a huge collection of books on music, as well as paintings by his second wife Soulla fill the rest of the space. This is where the senior executive editor of Gold, the monthly English-language business magazine, that covers the local business scene, the economy and the market, happily now works from.

“I consider myself one of the lucky people who gained something from the pandemic,” 73-year-old Vickers laughs again. “I became editor-in-chief of Gold in 2011, when it was founded. On turning 70 I started thinking that at some point we would need to give more duties to younger journalists who deserved to move up. During the the pandemic when we were all sent home, it became clear to me that the time was right, so when everybody went back I said I was staying home. And it has worked out! I still have oversight of everything that is going on in the magazine. Everything that is written is edited, corrected, and proofread by me, but I don’t have to be there any more. A young woman is editor-in-chief now, and, believe me, I don’t miss it.”

Being Gold’s senior editor is just the latest reincarnation of Vickers, possibly the best-known Englishman in Cyprus. This year, he celebrates the 50th anniversary of his island-based career.

Retford-born John readily admits that he didn’t have the slightest idea of what to do with himself on graduation from university — other, that is, than realising “that I didn’t want to be a teacher”. Yet, within a few months of landing in Cyprus, he was working at CyBC radio, thanks to British journalist Jim Morgan, who happened to be leaving the broadcast service and serendipitously suggested the young Vickers replace him minutes after they first met.

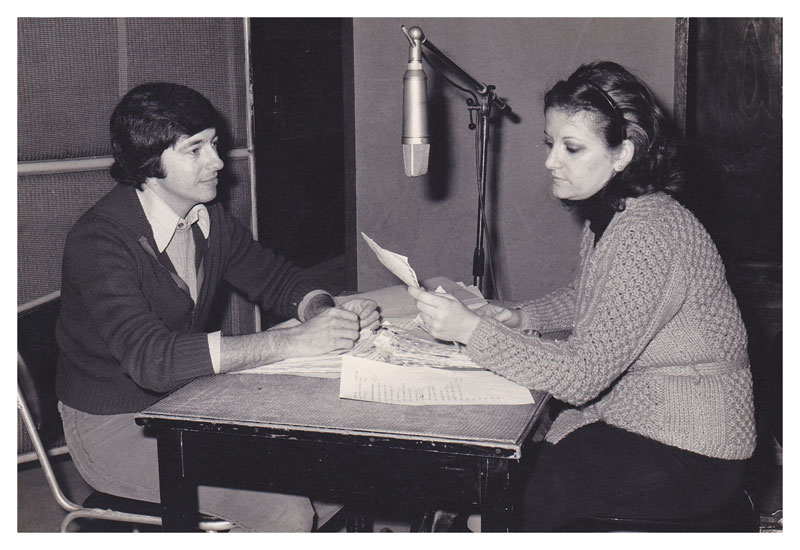

Request time with Vicky Bishara

Clearly, Morgan had a keen eye when it came to spotting new journalistic talent. In her book Samovar on the Table: A Family Memoir, Lana der Parthogh, then head of English and foreign languages radio programming, describes the advent of Vickers as follows: “We had a new member on the team who brought a completely different attitude and atmosphere to the bilingual Request Time. This was John Vickers, newly married to Lia, a teacher from Limassol, and on the island to stay, unlike the other male English announcers, who came and went. John had the required university degree, a good microphone voice and was a musician. He not only loved music, he knew it. His presentation was light and breezy, and within months Request Time became one of the top shows on the radio with a large following of Cypriot teens over generations to come.”

Vickers remembers his 17 years at Request Time very fondly. The bilingual (English and Arabic) programme he presented with Lebanese journalist Vicky Bishara was initially aimed primarily at listeners in the Middle East. The requests poured in in the form of letters, he recalls. Just sorting through them took hours every day.

When the war in Lebanon started “the letters stopped coming”, and it was decided to include requests from Cypriots. “We never looked back,” he says.

“I was getting paid for doing something I liked and I was good at it. I always loved music, I was brought up on the Beatles and in England I always listened to music programmes on the radio and read the music weeklies. But when I came here, there was nothing like this. So I took it upon myself to be for Cypriot listeners what other DJs had been to me when I was growing up…”

Vickers remembers a letter requesting he play a record that came from Turkey some time after the invasion. It was written by an American serving a sentence in a prison there.

“Because the letter came from Turkey we had to wait for a decision from the director general as to what to do about it. He decided we should read the letter on the air and play the record. And we did. Some years later I saw the film Midnight Express, and I realised that most likely the letter we got was from the same guy. His name was Billy Hayes and I do remember calling this guy Billy on the air.”

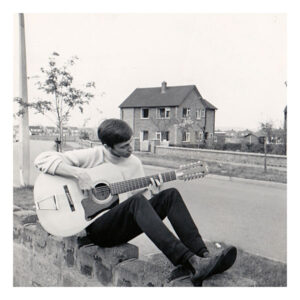

1966 in the UK playing guitar

Such is the affection in which Request Time is held even to this day, that Vickers cannot recall a week when he hasn’t accidentally bumped into somebody who recognises his voice (“..and remember, I stopped doing this programme in 1989”).

But the programme wasn’t the only source for his growing popularity. In 1975, a year after the invasion, two people approached John separately, each suggesting he compose music for one of their creations. TV director Andreas Constantinides asked if he would write the score for a documentary he was making about the return of prisoners of war from Turkey. Meanwhile, his CyBC boss Lana der Parthogh, having written a long poem about Cyprus, wanted it to become a song.

Vickers, who from his early teens has had been playing guitar and singing, agreed to both requests.

“I did some work on Lana’s poem but wasn’t really sure about it,” he remembers. “She asked me to play it for her and liked it. Then, Costas Tserezis, a journalist who owned the Argo art gallery in Nicosia, asked me to sing it… Constantinides, who happened to be in the gallery, came up to me and said: ‘You don’t have to write anything else for me any more. That is it. I can use it’. And he did. Both the song and the film ‘It was an island’, which took its name from the song, had an enormous effect on people. The docummentary was obviously very moving. The story was still very raw and people cried. My phone never stopped ringing… People wanted to know where they could get the song. In the end, I had to go to Athens to record it and it became an absolute bestseller.”

Was this his first time composing, I ask. John immediately sets off on a new story, taking us even further back. He was always composing songs. In 1971, when living in Nice, where he’d been sent as a student of French to improve his language skills, he once entered a song contest.

“The competition was actually for a French song but they took pity on me and let me sing as well,” he confesses.

The event was sponsored by the famous French singer Charles Trenet, whose great worldwide hit was the romantic song “La mer”. So taken was Trenet by John’s songs that he even arranged a record contract for him with CBS in Paris. However, feeling strongly that he had to go back to university in the UK to finish his degree, the 20-year-old Vickers opted not to stay in France.

“You know, people say one should follow their dreams, and maybe I did have a dream to be a professional singer but I guess it wasn’t strong enough to give up my university degree,” he says. “But I did accompany Trenet on guitar during his tours in Belgium and France, and we even did French versions of a couple of my songs together which was a great honour…”

Reverting to the 1974 invasion and the island’s subsequent division, I ask Vickers how, as a young Englishman, he had reacted to the events of July and August, 1974.

Since he and his family were living in Limassol at the time, the first news he received about the coup on July 15 came from his father-in-law.

“We just stayed at home. We didn’t know what to do. Then, on July 18, which was Thursday, Lana called and asked me to go to the radio station in Nicosia, to read the news bulletin and play some incidental music. On the Friday I drove to Nicosia, passed a tank at the the traffic lights at the entry to the capital, and got to the radio station. I read the news. An armed soldier in the studio was with me, listening all the time. My only feeble attempt to comment on the events was to inject a certain amount of irony into my voice whenever I had to say ‘according to president Sampson’.”

Because of the curfew, John slept on the studio floor overnight. Next morning, at 5.45am he drove to the der Parthoghs in Ayios Andreas. Nicosia was quiet. Then, as he parked his car in front of his friends’ house, the BBC announced the Turkish troops had landed in Cyprus.

“I went in. Both Lana and her husband George were awake. I said I was going to Limassol and at that moment we heard the gunfire.”

John spent the rest of the war in Limassol. He remembers how the town’s Turkish Cypriots were rounded up into the local stadium; also, the Greek Cypriot refugees from the north coming into the town. His family lived not far from their camp so they used to go there to help.

Along with his work on radio, John was gradually building an equally successful career in local English language newspapers, first penning music columns in the Cyprus Mail and the Cyprus Weekly, then as editor-in-chief of Hermes International, the Cyprus Review and Time Out Cyprus, and finally becoming editor-in-chief and senior editor of Gold magazine. Other projects include running an EU-funded EuroMed Info Centre in Brussels, editing a Greek-English dictionary for the Greece-based Patakis Publishers, translating numerous books from Greek into English and recording albums of his and other composers’ songs. He has attended 10 Eurovision song contests, eight of them as a journalist, once as a member of the backing group and once as composer of the song representing the island.

He even turned to acting, playing the title role of a young and innocent Cockney British Army soldier taken hostage at the Northern Ireland border and held prisoner in a brothel, in CyBC TV’s 1976 Greek-language adaptation of Brendan Behan’s play The Hostage. Learning to speak Greek was key to his life on the island but while he had a “good ear”, to ensure that he had the right intonation for his role, he went through the whole play with the assistant director every day after rehearsal.

Looking back, he says:” The fact that I wanted to learn the language and wanted to become part of the community, and also that I was an innocent, young kid who didn’t have any preconceived ideas about Cyprus, helped me a lot.”

As for now, he is making new recordings of songs he wrote between 1969 and 1972, inspired by the urging of an old friend from university days who recently died, and who had been the first person John played those songs to when he first wrote them. “Maybe after the summer, they will be ready.”

Fifty years in Cyprus, more than twice as many years as he spent in the UK. Does he think of himself as being more Cypriot than English?

“I think the things that made me what I am today, most of them happened in the last 50 years and not in the first 20. So I do think I have a lot of more of Cyprus in me than of Britain. “When people say I am so Cypriot because I can speak the language and I know so much about Cyprus I take it as a compliment, but in reality I would say only 90 per cent of this is true. I will never be 100 per cent Cypriot whatever that means … for example I will never go hunting and I am never going to love olives and I am never going to drink another cup of Cypriot coffee.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences