In an animal welfare activist who featured in a local film, THEO PANAYIDES meets a forensic neuropsychologist who was born fearless and now takes the same approach to abused pets and the criminally insane

Out in Gadsden county, Florida, Norma Torres is known as the “crazy dog lady”; she even has a T-shirt that reads ‘Crazy Dog Lady’, in fact she has more than one. The first one was given to her by an extremely poor woman (Gadsden is the second-poorest county in the whole state), and Norma was so moved that this destitute woman had made her a T-shirt – the point was to thank her for having helped with food for the woman’s dogs – that she never wore it, having more T-shirts made but saving the first one as a memento. It’s a cute story, but it tells only half the story; then again, ‘Crazy lady who helps stray dogs but is also a forensic neuropsychologist dealing in the treatment of the criminally insane’ is too long to fit on a T-shirt.

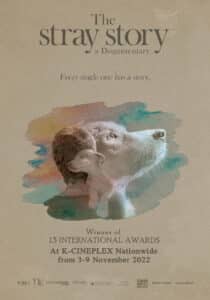

She’s a tiny woman, not even five feet tall – yet throughout her professional life, for 35 years now in Gadsden, before that in Washington DC and her native Puerto Rico, she’s dealt with violent, dangerous, often physically intimidating people, including murderers and serial killers. At the same time, she’s worked with animals – and is one of the volunteers featured in The Stray Story: A Dogumentary by local filmmaker Christina Georgiou, which is why she’s in Cyprus for a few days (we chat in Christina’s flat in Nicosia). The two strands don’t seem like the most obvious fit, but Norma doesn’t mind; she’s not offended to be called a crazy dog lady, she quips, after all “I work with crazy and I work with dogs, so it’s OK!”.

That said, there are parallels. The men and women she meets in prisons and psychiatric hospitals are a lot like the strays she rescues, damaged beings who’ve grown up believing that “interaction is based on violence”. She also works with those sentenced for extreme cruelty to animals – and it is extreme, from sexual abuse to cutting the poor beasts with razor blades – and I wonder what you can even do with a person like that; “You do exactly the same that you’d do with an animal. You have to start doing cognitive re-training”. In both cases, you can never show fear; with dogs because it confuses them, with the criminally insane because they thrive on it. “Their fuel is fear,” she explains. “They want to see you afraid.”

She’s always had “self-guidance”, as she puts it. She was difficult, but not delinquent or rebellious; “I was not in trouble ever, with anything. I was good in school, I respected the law”. She just knew her own mind, and refused to be forced into anything. “I was bored. My mother and father didn’t know what to do with me.” She taught herself how to cook, how to type on an old typewriter, how to read and write, how to add and subtract and multiply. The school ‘jumped’ her two years into third grade – then she got tested and it turned out she was performing at the level of seventh or eighth grade, so they jumped her again. She was done with high school by the age of 12, moving into so-called ‘advanced placement’ before going to college at 16.

That’s all very well, from an academic standpoint – but surely it’s not a good idea plunging a child among much older classmates?

“No, it is not a good idea!… My social life was a mess. Because I was not into boys – I was too young.” Norma shakes her head: “I was a freak. I mean, there was no other way to put it”. There was also her height, of course; she was always the tiniest in school – and “the boys, they are cruel. I mean, everybody’s cruel when you are short”. Two things helped her through this odd adolescence. The first was her love of animals, “the animals were my sanity. My strength, my direction, came directly from the animals”. The second was a natural gift for reading people, an emotional intelligence that made her the “unofficial counsellor” in school, the girl other girls came to with their problems. It’s a gift that’s been useful in professional life too. “Mental health is nothing else,” says Norma, “than being a sophisticated empath… If I can read you, I can understand where you are.”

She tells me of her first day in one facility, and an encounter with an inmate called Nathanael. “I am entering for the first time to this ward,” she explains in her slightly fractured English (Spanish, of course, is her first language, as well as the language she speaks to dogs when she first rescues them). “I see this heavy-duty, husky, more than six-foot-three African-American. I entered this ward without any protection and this person is at the entrance, walking back and forth. He looks at me and says, ‘Little lady, what are you doing here?’. I said ‘I come to work here’, and he said ‘Oh my…’” – she gestures to indicate a bad word which she prefers to pass over in silence – “‘we’re gonna eat you up!’. And I said, ‘Well, let’s see’. Then he said ‘Do you know that I was a boxer, and do you know that I killed three people?’. I said ‘Was that satisfying?’ – and he burst into laughter, because probably nobody had ever said that to him.”

This, you might say, was a case of meeting someone halfway, de-escalating the situation while keeping things on a friendly level. But of course it’s not that easy. “I mean, when you have somebody that is criminally insane, he is criminally insane… You have to be on your toes, because you never know when a psychotic break is coming.” Three days later, Nathanael “decompensated” – went nuts, basically – and the call went out for “Dr T” to make her way urgently to the “family room”. Norma hurried over to where several guards were trying to restrain the inmate, showing another side of herself. “I went over there and said, ‘What the fuck are you doing? You’re creating all this turmoil. I was in a meeting, you interrupted my meeting. Now go and walk to the restraining room, I’m going to put you in restraints, and we’re not going to do this show anymore’. And he said, ‘Yes, little lady’.” The big man allowed himself to be restrained, “like a good little soldier… And I said ‘Where is the knife?’. ‘How do you know I have a knife?’ ‘Because I know you, Nathanael, where is the knife?’ He said ‘In my underwear’. This big,” she adds, holding her hands about 10 inches apart. “It was a shank.”

How was she able to exert such authority? Partly, as she says, it helped that she wasn’t a physical threat. Partly it’s because she was fearless, and people could sense that. “I was a force of Nature,” she recalls with a laugh, “that’s a reality”. But they also sensed something else – the fact, for instance, that, having been born with immense self-belief, she didn’t have the insecure person’s need to impose her ego on others. “I never thought of myself as above anybody.” Above all, they saw that she cared: that she formed groups and programmes, that she made a point of celebrating birthdays, that she tried to arrange family visits, that she never read the inmates’ ‘official’ histories till she’d actually met them personally. In short, that she treated them with the same kindness and compassion – and discipline – that she brought to the stray dogs she rescued.

Working with animals had always been the dream – and she’s always been involved in animal welfare, alongside her work as a psychologist. (Norma was all set to study veterinary science – but it would’ve meant moving to the US, and her otherwise easy-going dad refused to let her go, as a minor.) There’s a certain congruence between her two fields, “because animal abuse at an early age is the hallmark of criminal behaviour… It’s the strongest correlation I have found, in all my years of practice”. Kids who torture puppies often grow up to be criminals – yet those same criminals melt when puppies are brought in to their place of incarceration. (It’s almost like they feel that the animals are forgiving them.) “I brought dog therapy into a ward that everybody was scared to go,” she recalls. “Everybody there had killed somebody, usually more than one person.” Incidents of violence dropped instantly, and precipitously.

“That’s the interesting thing, how the animals can heal them. There’s no clinical term for that, and there’s no way to explain it. If the word ‘magic’ exists, it’s a magic that only the animals know… I don’t know where the magic is – other than animals are capable of something we’re not capable of, which is unconditional love.”

Norma Torres has a certain belief in magic. “I connect here,” she says at one point, gesturing to indicate a gut feeling. (One reason why she agreed to be in The Stray Story was because Christina “vibrated very well to me”.) “I believe there’s something above us, whatever you want to call it, that protects me and guides me. And I feel it and I follow it. People reject it. I have never rejected it”. That guardian angel – or fate, or chance, or whatever – brought her husband David, “the wind beneath my wings” as she calls him. Her romantic life might’ve been permanently stunted by her years as a teenage ‘freak’ – but David, also a psychiatrist, asked her out (Where did you meet? “In prison!”), and Norma was initially a bit standoffish but soon discovered they had much in common. They now live on a 100-acre spread with deer, coyotes, foxes and horses in addition to a profusion of rescued dogs – 18 in the house, 40 outside – and an oak tree that’s 150 years old. “I go to my tree and I talk to Mother Nature, and Mother Nature tells me what I need to do. Crazy!… I mean, clinically I’m not crazy,” adds Norma, ever the scientist. “I’m just – different.”

What she values most in life is freedom, the “freedom to be myself”. (Not love? “Freedom is love,” she replies. “Because you choose to love… You open yourself to love.”) She’s a firebrand, an emotional whirlwind. She strikes up an instant bond, then embraces me at the end – “Are you a hugger?” – like a long-lost cousin. She makes noise, thus for instance the animal shelter in her town used to be a hellhole but “now it’s starting to change, because they’re sick and tired of me”. She’s a first responder; she’s worked all the natural disasters, from Katrina to Fiona. When it comes to her son Hermes (now a 47-year-old aerospace engineer) she was always “a Puerto Rican mum”, always present: “If he wanted to do soccer, I became a referee and I transported the team”. You can’t keep her down.

It’s a cliché that people who love animals tend to hate human beings – but Norma loves them both and tries to understand them both, straining to see the bigger picture. She recalls the time when she climbed that mountain in Puerto Rico, at four years old. “I was at the top of the mountain – because I wanted to see the horizon. I wanted to see what was there… Because I always knew there was something more, and I’ve been in search of that something all my life. And when I was able to connect with the crazy people – people who are referred to as crazy – well, that was the ‘more’.” Not just your ordinary everyday crazy dog lady.

Click here to change your cookie preferences