When he first heard that U.S. troops had toppled Saddam Hussein, Iraqi engineer Hazem Mohammed

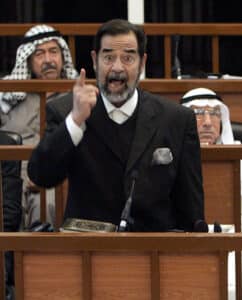

File photo: Saddam Hussein testifies during his trial at the fortified Green Zone in Baghdad, Iraq September 11, 2006

thought he would finally be able to find his brother, who had been shot dead and dumped in a mass grave after a failed uprising against Saddam’s rule in 1991.

It wasn’t just Mohammed’s hopes that were raised after the U.S.-led invasion in March 2003. Relatives of tens of thousands of people who were killed or disappeared under the dictator believed they would soon find out the fate of lost loved ones.

Twenty years later, Mohammed, who was hit by two bullets but survived the mass killing in which his brother perished, and countless other Iraqis are still waiting for answers.

Dozens of mass graves were found, testimony to atrocities committed under Saddam’s Baath Party. But work to identify victims of historic killings has been slow and partial in the chaos and conflict engulfing Iraq in the past two decades.

Iraqi engineer Hazem Mohammed at the site of an unearthed mass grave from which people where exhumed that are believed to have been executed under Saddam Hussein’s regime

“When I saw how mass graves were being opened, randomly, I decided to keep the location of the grave secret until a stronger state would be in place,” Mohammed said.

As exhumations dragged on, more atrocities were committed in sectarian conflict and amid the rise and fall of armed groups, such as Al Qaeda and Islamic State militants, as well as Shi’ite Muslim militias.

Today Iraq has one of the highest numbers of missing persons in the world, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross, which says estimates of the total range up to hundreds of thousands of people.

It was another 10 years before Mohammed led a team of experts to the site where he, his brother and others were rounded up as Saddam’s troops crushed a mainly Shi’ite uprising at the end of the 1991 Gulf War.At the time, they were forced to their knees next to trenches summarily dug in the outskirts of the southern city of Najaf, and shot. Tens of thousands of Iraqis were killed by Saddam’s forces during his rule.

The remains of 46 people were exhumed from the site, now surrounded by farms, but Mohammed’s brother was never found. He believes more bodies are still there, unaccounted for.

“A country that is not dealing with its past will not be able to deal with its present or future,” he said. “At the same time, I sometimes forgive the government. They have so many … victims to deal with.”

PAINFUL PROGRESS

According to the Martyrs Foundation – a governmental body involved in identifying victims and compensating their relatives – over 260 mass graves have been unearthed so far, with dozens still closed.But resources are limited for such a huge task. In a section of the ministry of health in Baghdad, a team of about 100 people processes remains from mass graves, one site at a time.

The department head Yasmine Siddiq said they have identified and matched DNA samples of around 2,000 individuals, out of about 4,500 exhumed bodies.

Lining the shelves of her storage room were remains of victims from the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war – skulls, cutlery, a watch, and other items that might help identify victims.

The forensic efforts are complemented by archivists studying stacks of documents from Saddam’s Baath Party, which was disbanded after his overthrow, for the names of missing persons yet to be identified.

Mehdi Ibrahim, an official at the Martyrs Foundation, said that each week his team identifies about 200 new victims. The names are published on social media.So far the foundation has processed about half of the 1 million documents in its possession, just a fraction of Iraq’s scattered archive. Most Baath Party-era documents are held by the government, while others were destroyed after the invasion.

Some atrocities are more quickly examined than others.

According to Siddiq, massacres committed by Islamic State militants, who seized much of northern Iraq in 2014 and held it for three violent years, have been prioritised.

The highest identification rate for victims was achieved for an incident known as the Camp Speicher massacre by Islamic State, a mass shooting of army recruits. “Most families declared their missing ones and most bodies had been retrieved,” Siddiq said.

The Martyrs Foundation says the killings resulted in about 2,000 martyrs, including 1,200 killed and 757 who remain missing.

In Sinjar, where Islamic State committed what U.N. investigators described as genocide against Iraq’s Yazidi minority, about 600 victims have been reburied, with some 150 identified.

Other disappearances remain unexplored. In Saqlawiya, a rural area near the Sunni town of Falluja, families are losing hope of discovering the fate of more than 600 men captured when the area was retaken from Islamic State by security forces.

Shi’ite militiamen seeking vengeance against Islamic State rounded up Sunnis from the town of Saqlawiya, according to witnesses interviewed by Reuters in 2016, U.N. workers, Iraqi officials and Human Rights Watch.

From her living room in Saqlawiya, furnished with just a carpet and a thin mattress, Ikhlas Talal wept as she scrolled through pictures of her husband and 13 other male relatives who disappeared in early June, 2016.

‘WE ARE NOT A PRIORITY’

Talal did not want to describe the men in uniform who took them away, fearing retribution. But she and other women from the neighbourhood have searched for their husbands, fathers and sons for years, travelling across Iraq and contacting prisons and hospitals – all in vain.

“The Iraqi government must take all steps to locate the disappeared and to hold the perpetrators accountable,” said Ahmed Benchemsi of Human Rights Watch.

The Martyrs Foundation and Iraq’s Interior Ministry did not respond to requests for comment on the Saqlawiya case.

Abdul Kareem Al-Yasiri, a local PMF commander whose unit is based currently near Saqlawiya, denied the PMF had any role in the disappearance of people from the area in the war with IS.

“These accusations are baseless and politicised to smear our troops and we reject them,” he said, adding that he believed IS was behind the disappearances.

Talal is seeking to have her husband officially recognised as a martyr so she could claim about a monthly pension of $850.

“We are not a priority,” she said, surrounded by half a dozen children who she barely manages to feed with the assistance of local NGOs and small-scale farming.

Questions remain even over the better-reported incidents.

Majid Mohammed last spoke to his son, a combat medic, in June 2014 before the Camp Speicher massacre. His name was not among the hundreds of victims identified by Siddiq’s team, and Mohammed remains in limbo. His wife Nadia Jasim said successive governments had failed to address the enforced disappearances.

“All Iraqi mothers’ hearts are broken because of their sons who disappeared” she said. “With all the time that passed since 2003, we should have found a solution. Why are people still disappearing?”

Click here to change your cookie preferences