It’s a political statement says hair historian STEFAN HANS

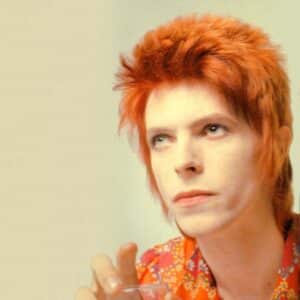

From Paul Mescal at the Baftas to Emma Corrin’s Governors Awards “mixie” haircut, the 1970s-inspired shaggy mullet is everywhere. But the now-popular “business up front and party in the back” style has a political history stretching far beyond the red carpet and the influence of pop icons such as David Bowie.

In fact, descriptions of mullet-like hairstyles feature prominently in the very first Anglo-Indigenous encounters of the 17th century.

In 1622, Plymouth colonist Edward Winslow described the Abenaki Native American leader named Samoset as having: “the haire of his head blacke, long behind, onely short before, none on his face at all.”

Winslow connected this early mullet to contemporary understandings of medicine and race. He wrote that “the Savage” wore clothing “like the Irish-trouses” and that Indigenous Abenaki were: “of complexion like our English Gipseys, no hair or very little on their faces, on their heads long haire to their shoulders, onely cut before.”

At a time when hair was key to community cultures, the mullet was written about with imperial and racist overtones. The style was associated with people considered rebellious by nature, part of the rhetoric used to legitimise the later use of violence against them.

David Bowie went through a series of mullet cuts

For Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), the combination of short and long hair was a rather puzzling, exotic sight.

His 1521 drawing of Irish soldiers and peasants shows the artist’s interest in hair customs beyond England. Just like changes in clothing, the foreign popularity of mullet-like hairstyles chronicled a world of new global connections.

Dürer himself spent immense time hairstyling. Contemporaries mocked him, speculating that he had a servant just for hairstyling. But he was adored, regardless, for his Christ-like appearance.

The Irish soldiers’ peculiar haircut (which might have come to his attention during a stay in Antwerp’s street of English merchant residents) inspired the Renaissance artist to reflect on cultural diversity.

In an age of global consumerism, knowledge about new hairstyles with peculiar combinations of short and long hair, like the mullet, could prompt reflections on fashion, taste and identity.

The rise of portraiture in the 16th century also sparked creative engagement with hair, as people increasingly thought about the ways they were seen by others. But short-and-long hairstyles remained counter-cultural at first.

Dürer’s contemporaries would have associated the mullet with humiliating punishments. German authorities, for example, condemned rebels to partial shavings, like having half of the beard cut every 14 days and the other half grown out.

Only in the 17th century did “provocative” long hair fashions become popular for men across early modern Europe.

Some, however, lamented the style as a sign of moral decline. Monarchs like Philip IV of Spain even forbade men to wear sumptuous fringes and hairlocks in 1639. Yet the adolescent monarch himself showcased his power, masculinity and youth through the stylish combination of lengthy, wavy curls and a full fringe.

Prohibitions failed in banning the spreading excitement around mullet-like hair and the 18th-century obsession with wigs gave rise to sumptuous hairpieces worn with short cut hair. Some wigs mirrored mullet-like shapes with short hair at the front and long hair at the back.

The style came back with a bang in the 1970s and 1980s, as the haircut became associated with the decades’ cultural revolutions and rock and punk scenes.

It was the 1994 Beastie Boys song, Mullet Head, that coined the word “mullet”, released the same decade as the Die Ärzte song, Vokuhila (Mullet) in 1999.

Largely rejected since then, the mullet is now in a renaissance. For mullet experts, such as Alan Henderson, author of Mullet Madness!, the style is so much more than a haircut: “It’s a way of life, a state of mind, an attitude … remarkable for its ability to offend, intrigue, entertain … startle, and even excite. Some find the mullet noble, handsome, even graceful. Others find it crude, low brow, or rebellious.”

The hairstyle’s significance has changed across history, but the story of the mullet is one of the power of hair to disrupt and provoke in societies across the world.

Stefan Hans is Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History, University of Manchester. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence

Click here to change your cookie preferences