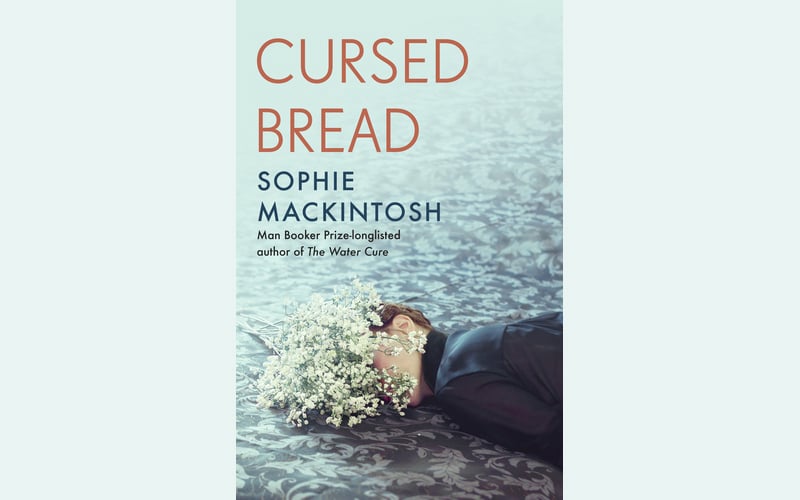

A good writer can write a bad book, but that doesn’t mean we have to forgive them for it. In Cursed Bread, Sophie Mackintosh shows off her capacity to craft beguiling sentences and evoke an atmosphere of shadowy obscurity that might generously be described as Kafkaesque. But she does so in a way that feels more like pseudo-profundity than the haunting resonance that one assumes she was going for.

The disappointment partially lies in the fact that the historical events that inspire the novel sound so ripe for a terrific story. The 1951 eruption of mass hysteria, madness and bloodshed in the little French town of Pont-Saint-Esprit which left 50 residents institutionalised and several dead has proved a fertile breeding ground for conspiracy theories from CIA experimentation to contaminated grain (hence the ‘cursed bread’). Who doesn’t love an unsolved and spectacularly gory mystery? Well, it would seem that Sophie Mackintosh doesn’t since she decided to turn her source material into a tepid exploration of horniness instead.

Elodie, the narrator and central figure, is married to a baker who is given no name or personality aside from the fact that he loves baking and has no apparent interest in his wife. Consequently, Elodie is really horny and ‘was sometimes jealous of the dough my husband put his hands into, worked so tenderly and tirelessly with, up to the elbows’. Once the mysterious and glamorous Violet and her husband, ‘the ambassador’, move into town, Elodie’s desire spreads from her husband to both Violet and the ambassador, aided partly by the fact that she thinks Violet might want to screw the baker and by the sight of the ambassador choking Violet, both of which become permanent fixtures in Elodie’s fantasy life.

Writing from a seaside town after the incident, Elodie retells and reflects on her (non) relationship with the objects of her lust, interspersing these with stories of how she acts out her desires with strangers now her husband is dead (a victim of the cursed bread). Violet and the ambassador turn out to have been a pair of astonishingly cruel sadists, but we don’t know why and given the flatness of the characters – and despite the magnitude of their ill-deeds – we struggle even to care.

And that’s it, really. When we get to the actual insanity and gore, it’s very well done; Mackintosh can horrify with ease and grace, just as it feels like she could do almost anything in words with ease and grace. Which is why it’s so hard to forgive the fact that while trying to write a novel of dark ephemerality, she seems to have rather lazily produced a novel of greyish hollowness.

Click here to change your cookie preferences