With a generous state subsidy ‘a lot more women than we realise choose to freeze their eggs’

Cypriot women are increasingly “shutting their ears to outdated ideas” and moving to freeze their eggs, largely spurred by government subsidies seeking to tackle the country’s low birth rate.

Figures shared by the health ministry, reveal hundreds of women have sought out the €2,000 state funding to cover a brunt of the cost of freezing eggs.

Specifically, since the scheme began in 2021, eligible for women over 35 (or younger due to a medical condition), 1,298 applications were approved.

The cost ranges between €2,500 to €3,500. Cypriot nationals or yellow slip holders can apply.

“If one takes into account that most women have their first child after the age of 32, modern lifestyle can be the obvious explanation of why women are increasingly freezing their eggs,” Karolina Stylianou, senior officer at the public health services told the Cyprus Mail.

“Family planning is not a priority for people under the age of 30.”

Melina Menelaou, manager at Limassol-based Genesis Centre for Fertility & Human Pre-Implantation Genetics, said she has also observed an increasing interest from women in the last two to three years since the government funding came into place.

Additionally, she explains, gynecologists are now far more open in their conversations with women about fertility and what options they have.

“It is historically a very taboo topic in Cyprus and it has to do with our society that expects women to get married and have a kid right away.”

Deviations away from that are a struggle to accept or even contemplate. “It’s hard enough for people to admit to having IVF, let alone freezing their eggs.”

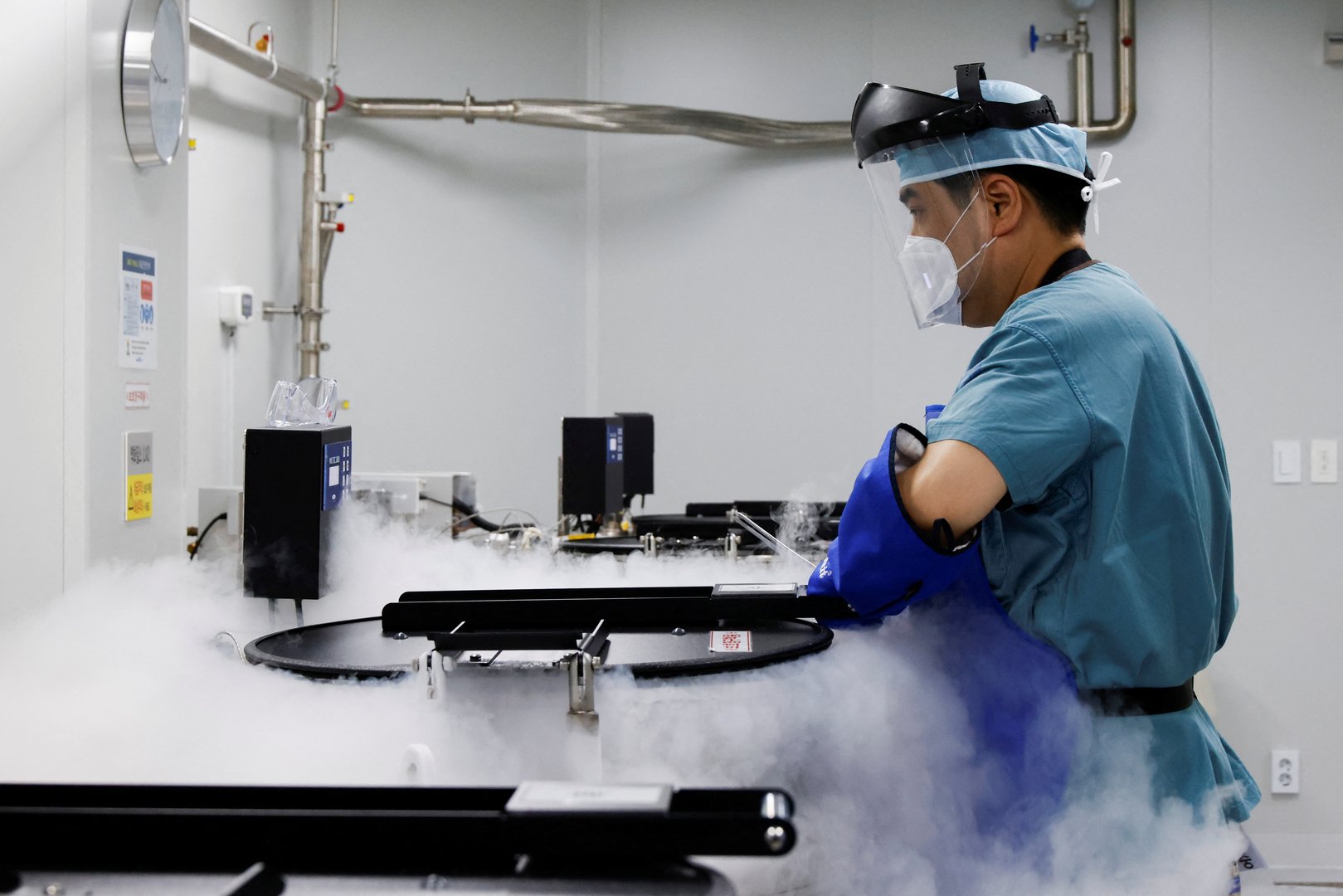

Similarly, Lasse Ribergård Rasmussen the PR and communications specialist for Cryos, described as “the world’s largest sperm and egg bank” with facilities in Nicosia, explained women are increasingly interested in freezing their eggs since they postpone motherhood for a host of reasons.

“They would like to have higher education, progress in their career, waiting to find the right partner or even religious reasons. Postponing pregnancy and parenthood can reduce the chances of a healthy pregnancy as women’s prime reproductive years are in their 20s and early 30s.”

The increasing interest is reflective of patterns and policies observed across the world. In the UK, egg freezing and storage increased 64 per cent between 2019 and 2021, according to a report from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority.

Similarly, Japan will also begin subsidizing egg-freezing for women amid declining birth rates.

With Cyprus also concerned about a low birth rate, last week the government announced a €1,000 increase in IVF treatment subsidies, now amounting to €3,500.

Health Minister Popi Kanari explained the funding was specific for the first IVF treatment, describing the move as “necessary to increase our population”.

Closer to home, Menelaou credits Disy MP Savia Orphanidou for many of the changes surrounding the taboos in Cyprus.

Orphanidou grabbed headlines a few years ago when she chose to have a child as a single mother using a sperm donor. Using her voice and role in parliament, she rallied against the long procedures currently in place and the lack of financial support for single parents.

She also admittedly went against many of Cyprus’ conservative values – not only being a single mother, but for rejecting the idea of marrying to have a family, and being open about the fact that she did not find a partner she deemed suitable but did not want to keep waiting to have a child.

Although she got some hate for it, Orphanidou has become a source of support for many women who now turn to her with similar questions, seeking advice and encouragement.

“There shouldn’t be any taboos and if there are, we should just shut our ears to them and move forward,” she told the Cyprus Mail.

A lot more women than we realise choose to freeze their eggs and get pregnant using IVF, she adds.

Menelaou verifies this, saying plenty of women opt to freeze their eggs at the clinic and no one outside of those walls know they have chosen to do this.

According to Orphanidou, there are three categories of women eligible for the government grant.

The first is for women that have premature menopause who can’t leave pregnancy for a later time. The second concerns women diagnosed with cancer who have to wait for a certain amount of time to ensure a safe pregnancy.

Lastly are personal reasons. “Maybe one woman marries and doesn’t want to have kids. Maybe she wants to study, go abroad, there’s a host of reasons.

“Modern life is hard and you have to plan ahead,” Orphanidou explains.

Click here to change your cookie preferences