Courts in Israel have developed it beyond the confines of absurdity

The political turmoil in Israel came to a climax last week when its parliament, the Knesset, passed a controversial law that according to its opponents licenses the government to act unreasonably and according to its supporters prevents unelected judges from inflicting their elitist views on the democratically elected government of Benjamin Netanyahu.

The new law states that “those holding judicial power…including the Supreme Court sitting as the High Court of Justice shall not hear a case or issue an order against the government, the prime minister or a government minister on the reasonableness of their decision.”

It is a little odd that judges sit in judgement on whether government decisions are reasonable. Governments are elected and judges are not. What is reasonable in politics is not as obviously a justiciable issue as it is in private civil law. The objective reasonable standard of behaviour expected of a defendant in a negligence case does not transplant well when applied to decisions of a government minister. In politics there is no objectively reasonable standard of behaviour on which to judge decisions of government ministers. Or is there?

It is generally accepted that it is beyond the power of any government minister to act corruptly, dishonestly or in bad faith. But what about decisions deemed unreasonable?

The answer to that conundrum requires a brief excursion into the origin of the reasonableness challenge that was developed by the head of the English Court of Appeal, Lord Greene in 1947, in a case just before the creation of the state of Israel in 1948.

He ruled that the courts in England do not sit as an appeal court from decisions of the executive. Their jurisdiction is supervisory which means that judges are entitled to scrutinise the decision-making process to rule on whether a government minister directed himself correctly in law, and, where the law expressly or by necessary implication requires the minister to take into account certain matters and ignore others, that he has actually exercised his discretion accordingly.

More out of perfectionism than necessity, Lord Greene then added that if a decision is so absurd no one in his right mind could ever dream it was within a minister’s powers, the court would rule it outside his powers.

It is in this narrow sense that reasonableness features as a ground of challenge, although it is more correct to categorise an absurd decision as beyond ministerial power in the same way as dishonest or corrupt decisions are beyond the discretion given to any minister.

It looks as though in the eyes of the Netanyahu government the reasonableness ground of challenge has been developed by the courts in Israel beyond the confines of absurdity.

The power of judges to deem unreasonable the present Israeli government’s decisions hampers the implementation of Netanyahu’s highly controversial policies, which many in Israel including the Palestinians find fundamentalist, extremist, nationalist and wholly unacceptable.

But he argues they are not unreasonable given the right-wing religious politics of his government and in deeming them unreasonable the present crop of Israeli judges have overstepped what the separation of powers allows the judiciary.

Unreasonableness is rarely a ground of challenge in England because of the requirement for court permission to seek judicial review of government action for which one needs to show an arguable case. And it is very difficult to show arguability on the ground that an executive decision is absurd, so few barristers plead it.

Ministerial decisions in the UK are usually made by civil servants who are entitled to act on behalf of government ministers although in some cases decisions are reserved for decision by the minister personally. In either event, there is input from civil servants who these days are guided by a booklet called the Judge Over Your Shoulder (JOYS) – now in its 6th Edition – on how to avoid legal pitfalls.

In light of the booklet, government decisions contain detailed reasons designed to make them judge-proof and not capable of being branded absurd.

By contrast a challenge to a government minister’s decision that ignores relevant matters or takes into account extraneous matters is not a challenge to its reasonableness but to the process by which it was arrived at.

It is the same with breaches of natural justice where a person is not heard before an adverse decision is made against him; again it is the process in failing to hear him that attracts judicial scrutiny and not the reasonableness of the decision.

More recently government decisions frequently engage rights protected by human rights law – the European Convention on Human Rights for example or its equivalent in Israel.

Where such rights are involved, government decisions must not be in breach of the human rights of those affected. As most human rights are qualified, if a government minister’s decision overrides human rights it must be proportionate to a legitimate aim.

Indeed proportionality is nowadays a free-standing ground of challenge in public law across Europe. It is a lot easier to evaluate objectively than reasonableness because it is concerned with degree whereas reasonableness is value-laden.

All these avenues of challenge apart from reasonableness would still be available in Israel. However the problem is that the political divide there has now spiralled out of control into a constitutional crisis.

The Israeli Supreme Court will now rule on the constitutionality of banning reasonableness as a ground of challenge against the government sometime in the autumn. The amendment is undoubtedly to a foundational constitutional law since it is the first of a series of proposed amendments to overhaul the judicial arm of government in Israel root and branch.

The Supreme Court will therefore have to bite the bullet and decide whether the government of the day at any given time can change the Israeli constitution – or its basic law on the judiciary if you prefer.

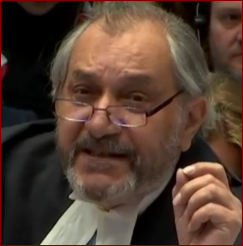

Alper Riza is a King’s Counsel and a retired part time judge in England

Click here to change your cookie preferences