When a short book takes you longer than it should to read, there are a few viable explanations. First, the writing was so dense that you needed to take time to untangle it; second, the writing was so gorgeous that you read everything more than once to savour it more; third, the book just didn’t make you want to read it, so all of a sudden, doing other things became enticing enough to stop reading. For this reader, at any rate, Owlish falls into the third category.

This is a shame, because the idea of a fantastical version of Hong Kong (Tse calls hers Nevers) in which a repressive regime creates a world divided between the ordered surface of skyscrapers and foreign tourists, and a surreally labyrinthine underworld of magic and murkiness is a great one. Even more so when the multi-layered city is paralleled with the divide between a character’s daily life as an academic, ‘dumping dry, insipid words into research-paper-shaped moulds’, and his fantasy life in which he can indulge his dreams – which mostly involve a pretty serious doll fetish.

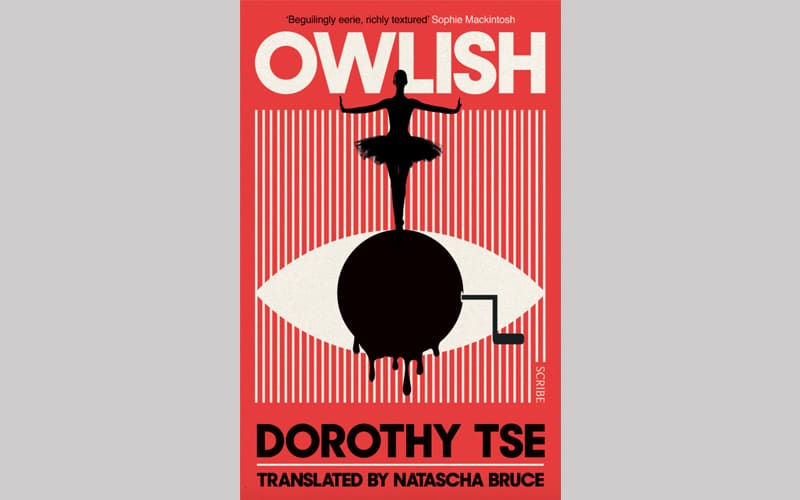

Tse’s premise is a powerful one: her protagonist, Professor Q, describes himself at work as a ‘mannequin’ only to fall in love with an enchanted mechanical ballerina and exclaim ‘A woman! He had really found himself a woman!’ The irony of humans being reduced to automata and being so degraded as to believe that another automaton might be their release into humanity is compelling.

The problem, however, is that there just isn’t anyone to root for. Professor Q has a wife, Maria, who is beautiful, caring, but frigid. She dreams of a peaceful retirement while diligently working a government job that she secretly knows will contribute to the impossibility of fulfilling her dream. Is her frigidity enough to justify Q setting up a love nest on a secret island in which he rides a rocking horse naked with his life-size doll that he enjoys manipulating for the fulfilment of all his stunted desires? Not for me.

Then, when Maria finds out about Q’s affair, I was hoping for some action. Instead, she just pities him. And, fair enough, he’s pathetic. And perhaps the whole point is that in Nevers everybody suffers and everybody is dehumanised, so everybody should be pitied. This might be true, but it’s also unsatisfying, especially when in the background, protestors are going missing, migrants are hurling themselves from windows, and the media is telling blatant lies. When there is so much against which to rebel, hiding from it by molesting dolls or burying yourself in work, just feels infuriating.

Click here to change your cookie preferences