In the highest ranked United Nations official born on the island, Agnieszka Rakoczy meets a man with a varied international career spanning from the depths of poverty to narrowly missing a bomb attack

There is an old photo in my interlocutor’s apartment – a woman with strong features, a moustachioed man and five children, all looking directly into the camera, I am told. “These are my Armenian grandparents and their children,” 85-year-old Benon Sevan, the highest-ranking United Nations official ever born on the island, says.

“They came to Cyprus from Adana in Turkey in 1922. My mother was only six months old when they arrived. My grandmother had three sets of twins – two boys and four girls. But one of the daughters was lost during the massacres so they came here only with the remaining five.”

Benon Sevan in a UN role

I keep looking at the picture every time I visit Sevan to talk about his life – it is so full of twists and turns that it is impossible to limit our interview to a one-off face-to-face session. Instead we divide our conversation into chapters, interlined with lunches and coffees and discussions about books and cats. There are meetings we devote entirely to his childhood in the Arab Ahmet district of old Nicosia, and others during which he tells me about the years spent in Western New Guinea.

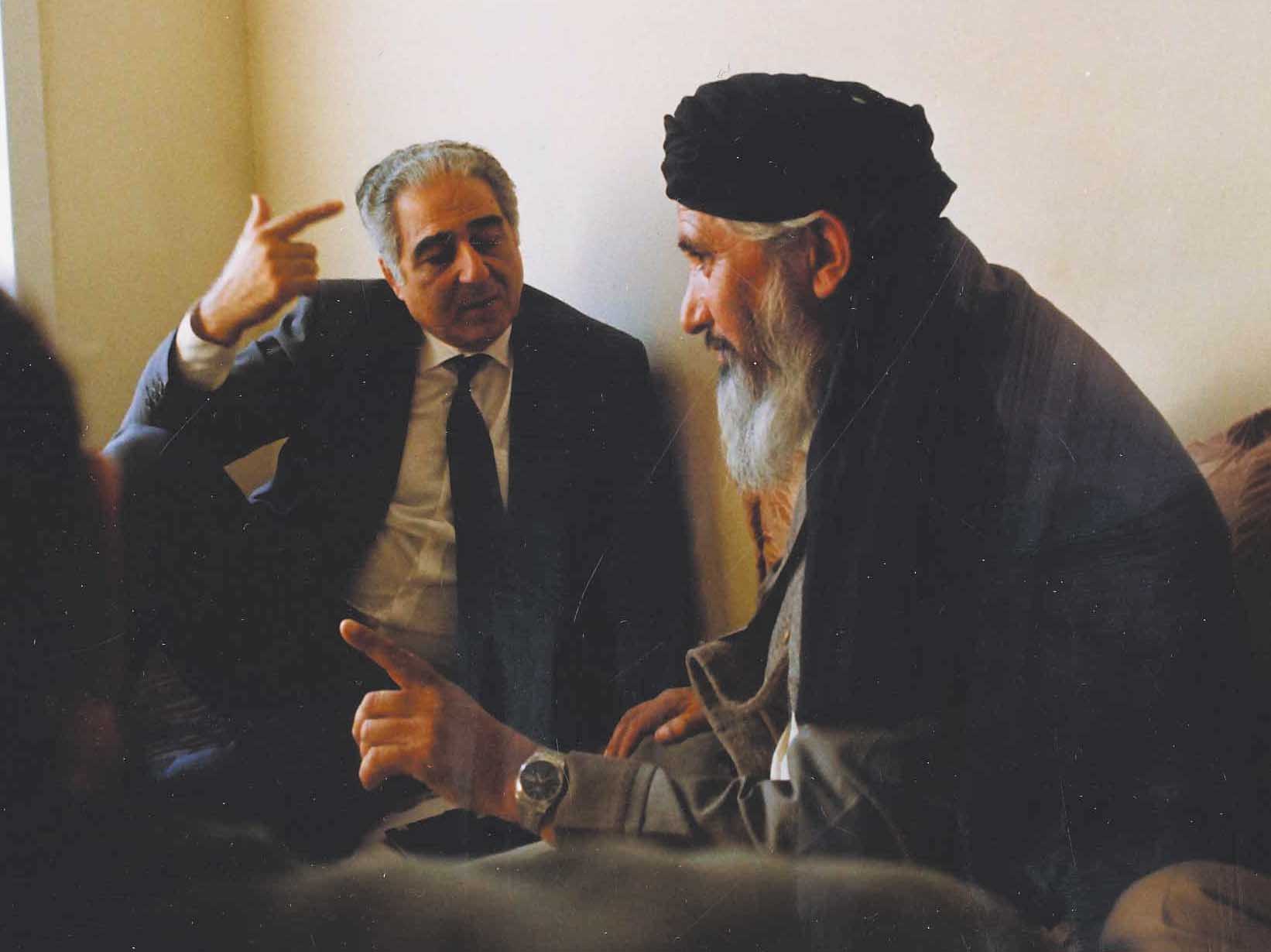

There are many discussions about Afghanistan, where he worked in the early 1990s, and Iraq where he ran the Oil for Food programme. Inevitably, we also talked of the occasions when his life was endangered – “three times in Afghanistan”, “once in Baghdad”. In the case of the latter, Benon survived the infamous suicide bombing attack on the Canal Hotel in Iraq in 2003 in which22 UN staff members were killed, simply because he “changed the place of his meeting a minute before the bomb exploded”, adding that he felt guilty for having survived when his friends and colleagues were killed.

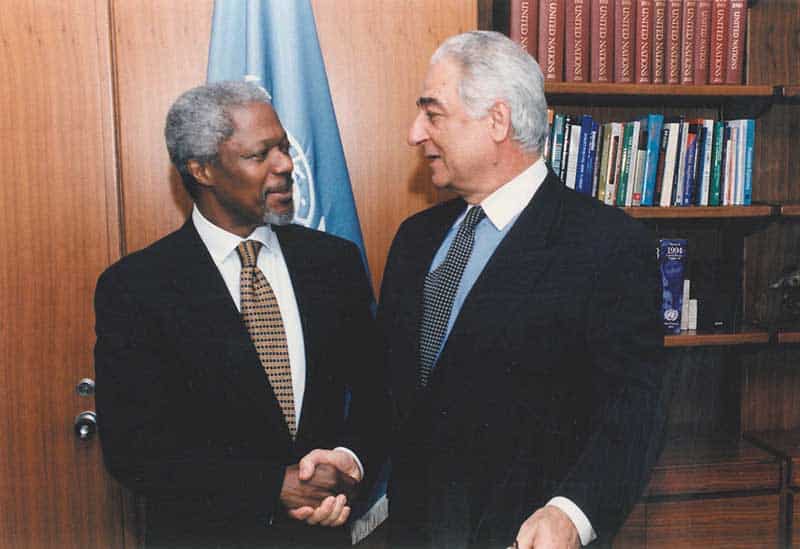

Sevan with Kofi Annan

It is hard to believe that all of this happened to the same small boy who spent his childhood locked within the Venetian walls of old Nicosia. That was a small world, he sayd, “I used to call it ‘the Armenian ghetto’. When my grandparents moved there it was a mixed Armenian-Turkish neighbourhood. Like many other Armenians who came from Turkey, they spoke only Turkish. The Armenian church was there and, of course, many of their neighbours were also from Adana so they had known each other from before. Arab Ahmet was a place full of memories. When people visited each other, the present didn’t exist. They would recreate the past and just talk about it. They all had a dream to go back to Adana and they died having this dream.”

At the same time, Sevan says, the Armenians of Arab Ahmet lived very closely with their Turkish Cypriot neighbours. “There was no discrimination, no animosity in our lives. We all lived together. I always want to pay tribute to my grandparents for this. After what had happened to them in Turkey, they had every justification to hate Turks but they didn’t. We grew up like brothers and sisters.”

The two first languages Sevan learnt in his life then were Armenian and Turkish. “I started learning Greek only when I went to school but they never taught us well.” This is why, when he came back to Cyprus after many years abroad, he enrolled in an intensive Greek language course at the University. “I did it because I really wanted to be able to read the local newspapers and talk to people.” Speaking six other languages, he felt it was imperative to speak Greek.

Fleeing Turkey with nothing, Sevan’s grandparents struggled when they first arrived and it was only when Sevan’s uncles grew up the family situation changed for the better.

“One of my uncles became a successful mechanic and my other uncle, during WWII had a contract with the British army for the laundry. They both supported my grandparents. It was tough for all Armenians who came here. I admire them. They never begged. They were proud people and they did whatever jobs they could get. And they sent their children to school to educate them to the best of their ability.”

For the first six years of his education, Sevan attended a small school located in in the yard of the local Armenian church. Later he was sent to the well-known Melkonian Institute, established in Nicosia in 1926 by brothers Krikor and Garabed Melkonian, who were prominent tobacco traders from Egypt. By the time Sevan was there, it had become a large boarding school catering to students of the Armenian diaspora from many countries.

It was here that luck smiled at him. A childless Armenian couple from the United States, themselves survivors from the massacres, wrote to the director of the Melkonian, offering to sponsor a child for studies in America. Young Sevan was recommended and accepted.

He must have been a very smart student to be chosen, I remark, but Sevan demurs. “I don’t think I was that smart,” he says. “I think it was rather that some others were less smart.”

Smart or not, he ended up in Cleveland, Ohio, studying history at Fenn College for two years before enrolling in 1960 to study history and philosophy at New York’s Columbia University on a full scholarship, followed by a further degree from Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs. Passionate about photography since childhood (“I wanted to become a photojournalist”), Sevan started taking pictures for newspapers at the weekends to earn additional income.

He also landed a job as research assistant to India’s former ambassador to the UN, Arthur Lall. “It was a fantastic job because he was writing a book on multinational negotiations. Every day we would discuss what he would be working on and I would go to various libraries to research the subject. I learnt a lot.”

His next job provided him with another learning opportunity. In 1965, on the cusp of graduating, the 28-year-old Sevan joined the photo section of the Radio and Visual Services Division at United Nations headquarters. Writing captions and context for all the photos taken at official meetings of the organisation proved to be “a great introduction” to the international system that “opened a lot of doors since I had to know everybody”.

A few months later he was assigned to the Department of Political Affairs before a career-defining move to the UN’s Special Committee on Decolonisation. In the 1960s, this was “a big thing” since at the time “so many countries were gaining independence”.

So it was that in 1968, Sevan found himself setting off on his first UN mission, bound for Western New Guinea as a UN Observer to an upcoming plebiscite.

“We were to explain the voting process to the people, but the truth was, the whole thing was a foregone conclusion. The people were never really given another choice. However, the place was amazing and I fell in love with it.” So, when less than a year later he was offered a further position there he leapt at it.

For the two years that followed, Sevan was in a place where time seemed to stand still.

Sevan loved the place so much that he learned the local language, married a young Balinese woman who, when his job finished in 1972, took back to New York.

Sevan with former soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev

Laughingly, he recalls how he wrote to his aunts in Nicosia who had been pressing him to get married, and told them that he had finally done so. “Terrified, since the only photographs of local women they had seen were of the half-naked wives of headhunters, they wrote back to me asking me not to go to such an extreme.” The marriage was not to last long. “My wife was from a big family, she didn’t speak English, and she couldn’t adjust to New York. She went back to Bali. We are still in touch.”

The years spent in West New Guinea influenced Sevan’s later life. “What I saw there reinforced my stoicism… made me realise that material things don’t make one happy,” he says.

On returning to New York, he began steadily climbing the UN career ladder, including carrying out special political assignments on behalf of the Secretary-General. In 1980, he married his second wife, Micheline, also a UN employee. They had one daughter, Jasmine. Sadly, Micheline passed away a few years ago.

The higher Sevan rose in the UN system, the more responsiblites he was given. “Most of the time I was doing two or three different jobs at the same time,” he notes, which often meant that on moving on, he would be replaced by more than one person.

We are going through various photos related to his UN work – Sevan smiling next to Russia’s FM Sergey Lavrov (“a good friend”), various Middle East officials, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, Pakistan PM Benazzir Bhutto. “I have even met Osama bin Laden although at that time he was just one of the Saudi sheikhs”.

Scanning his CV, I quickly realise that focusing on just the positions he held in the UN alone would be impossible to enumerate here. Did he enjoy working in such a large organisation? “Of course, yes,” he answers without hesitation, but “it was a different UN than now. Now I have difficulties to relate to it.”

Asked which of his numerous UN jobs had the biggest impact on him, he points to his assignment in Kabul, where he served with the rank of Assistant Secretary-General, as the Secretary-General’s Personal Representative in Afghanistan and Pakistan; and also to Iraq, where as Executive Director of the Iraq Programme, with the rank of Under-Secretary-General, he was responsible for the overall management, coordination and supervision of the implementation of all the UN’s humanitarian activities, the so called Oil-for-Food Programme.

On Kabul, he puts it very simply. “Because I was there at a crucial time when everybody thought that once the Soviets withdrew there would finally be peace, and because there was such terrible poverty and suffering all around — children with no arms, no legs — I identified very strongly with the Afghan people. And I really tried, literally working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in an effort to help, to encourage them to work together despite the differences, to sacrifice their own personal ambitions for the sake of the people who had suffered for too long, who for too long had been used by foreign powers as mercenaries, being killed in the proxy wars of other people.”

He shakes his head when he thinks where the country is now and how all the efforts to change its destiny have failed. “The truth is that unless a plan is an Afghan plan, agreed by Afghans themsleves, and not by foreigners, it will never work. It will take years for Afghanistan to become normal… And meanwhile the suffering that is going on there is unbearable…”

What about the Oil-for-Food Programme that he maintains delivered some $31 billion worth of humanitarian supplies and equipment to Iraq in exchange for 3.4 billion barrels of Iraqi oil valued at about $65 billion by the time it terminated in 2003? This, his biggest assignment ever, was the only job he ever held where he was accused of corruption.

Sevan remains remarkably candid when discussing the charges that ultimately ended his UN career. “I know I didn’t make any deals and I can look at myself in the mirror without shame,” he insists. “In Iraq we did a lot and we made a huge difference in the daily life of people. I am proud of what we did there.”

Sevan was charged in New York in 2007 for allegedly receiving $160,000 in kickbacks from sales of Iraqi oil under the government of Saddam Hussein. He shrugs his shoulders when I ask him about it, terming the amount alone as ridiculous. “I managed a $64 billion programme and I would compomise my career for this and then report it publicly?” he asks rhetorically.

“The truth is that when the US invaded Iraq it wasn’t authorised by the Security Council and Kofi Annan said in an interview that the invasion was not legal. That is why they went after him. And then his friends sought to distance it away from him and chose to scapegoat me, coming as I do from a very small country. So they accused me of taking millions of dollars but then couldn’t find anything. I authorised them to examine any account I had, and also those of my wife and my kid. They couldn’t find anything. After spending close to $40 million, from the programme’s account, they accused me of receiving $160,000 in kickbacks. But the truth is that the only thing I got free from Iraq when I had official meetings there was coffee…

“It was an effort by the Americans to divert attention from their disastrous invasion of Iraq, using me as a scapegoat,” he says. The total was given to him over a period of years by his aunt and was “meticulously reported” each year on his financial disclosure form. “Imagine, me supposedly receiving kickbacks and reporting the amount in my financial disclosure forms”.

Is he angry with the way the UN treated him and with Annan personally for not defending him? “I am disappointed. During the last session of the security council concerning the programme, he had paid special tribute to me for performing, as always, beyond the call of duty. He was under pressure himself personally and decided to remain silent concerning my situation.”

Why, after the final report was published and charges announced, didn’t he choose to go back to New York and face the accusations? “You know, this indictment came eight months after I had come back to Cyprus. And I actually wanted to go back and fight it but my lawyer advised me very strongly not to go. He said ‘Benon, there is no chance you will get justice. They have decided already’. That is why I never went back.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences