A recently uncovered 1959 letter from Sir Hugh Foot writes of his barely hidden reservations on the future of Cyprus. It’s a sobering read

This year marks 50 years since the Turkish invasion, 60 years since the UN arrived and 64 years since independence from British rule, and while reams have been, and are still written about ‘the Cyprob’, when new information comes to light it can often add a new dimension to the historical record.

A previously unpublished letter from the last British governor of colonial Cyprus. Sir Hugh Foot to well-known female Cypriot artist, the late Thraki Rossidou Jones, dating from March 1959 would probably qualify as an important find in that respect.

The letter was recently uncovered by the artist’s son Gavin Jones. His mother died in 2007 and he found the document among her papers, he told the Cyprus Mail.

Jones said his mother had led an extraordinary life and had left mountains of papers, cuttings of newspaper articles, letters and photographs which he had never really sat down to examine in detail until recently. He found the typed letter in a faded envelope, he said. Sadly, he does not have the letter she sent to the governor.

A few readings of the letter show that although on the face of it, Foot appeared upbeat about the London and Zurich agreements – signed less than a month before – reading between the lines, the tone was more one of resignation rather than jubilation that the strife was ending.

He spoke about the “many doubts and reservations” of the Cypriot people towards looming independence but also wrote of the relief in escaping the violence of the past years.

“It would have been a wretched business to continue into the future with a continuation of the situation which we have known in the past few years,” he wrote, clearly referring to the 1955-1959 Eoka struggle to end colonialism on the island.

He went on to call the London and Zurich agreements “the best possible result” but in a way that suggests it was actually the lesser of three evils. “Partition would have brought disaster to the majority of the people and I am sure that any attempt to force through Enosis [union with Greece] would have caused a major conflict, not only in Cyprus itself but also in the wider field of relations between Greece and Turkey,” Foot wrote.

“We have to work a complicated settlement but Cyprus was a complicated problem and if we can preserve and improve the present spirit of goodwill I think that an independent Cyprus can go forward in political progress and economic prosperity,” he added.

It was not long, barely four years, before it became apparent that his words about the spirit of goodwill had fallen on deaf ears and have still not been heard 65 years later.

Jones would agree with the assessment. He believes the letter unwittingly offers a window into the mindset of not only Foot but, he suspects, probably that of the British Foreign Office.

“It concludes that the settlement between all the parties which was reached was the best of a bad job and yet at the same time one has to read between the lines as to what it doesn’t say,” Jones said.

“I feel that it’s more a question of Britain doing a Pontius Pilate and was glad to get shot of the problem. In that regard I feel that the letter is also prophetic as discord and violence was soon to erupt at the end of 1963, the legacy of which remains to this day,” he added.

So why was a British governor writing a letter to a Cypriot artist?

Jones explains that his mother was the daughter of Kyriacos Rossides, who from 1925 until 1931 was a member of the Legislative Council, a 15-member body set up by the British colonial authorities “to give a veneer of home rule”. It comprised representative numbers from both communities.

Her father represented the Karpas peninsula and Mesaoria plain. He was also president of the Farmers Union for a time and promoted tree planting and tobacco growing.

However, after the uprising of 1931 when a group of Greek Cypriots burned down Government House in Nicosia demanding Enosis, the council was dissolved by the British and Jones’ grandfather and others were exiled or put under house arrest.

“With politics and nationalism very much part of my mother’s formative years, she carried on this tradition in adulthood,” said Jones.

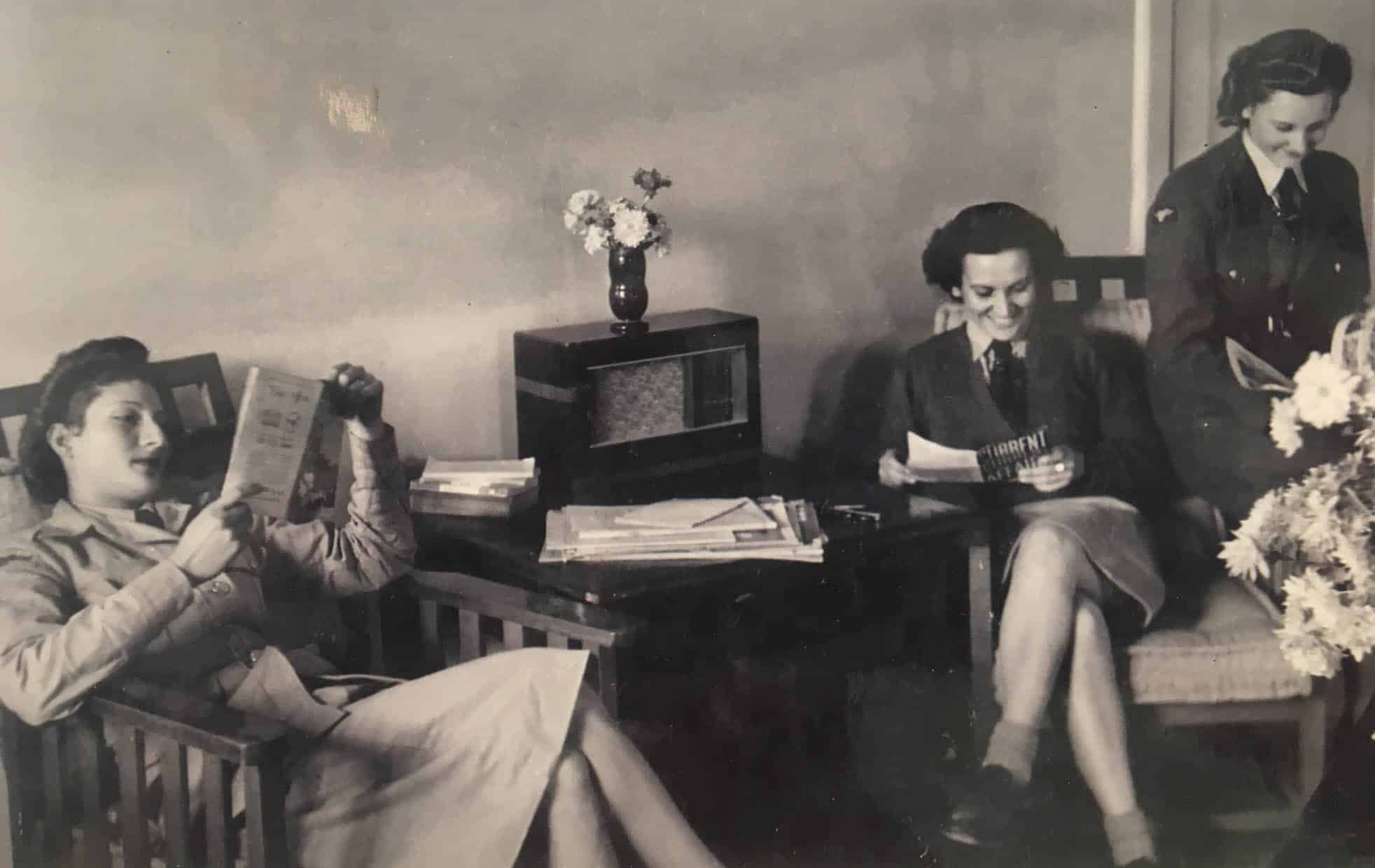

She joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force during World War II and met his father who was in the RAF while they served at Athalassa in Nicosia.

He said that moving newly married to England after the war, “she became a sort of unofficial roving ambassador and promoted the interests of Cyprus whenever and wherever the opportunity presented itself”.

The correspondence with Foot, he added, “confirmed her efforts in this regard as she obviously conducted correspondence with those who could influence events in order to do her bit”.

His mother retired to Cyprus in 1968 and she continued an active political life in tandem with her painting career.

Sir Hugh Foot died in 1990 at the age of 83. He had also served as colonial secretary on the island from 1943 to 1945 and moved on to Jamaica, then Nigeria before returning to Cyprus as governor in December 1957 at the height of the Eoka struggle.

An article in Time Magazine in July 1958 laid out how Foot had released the text of a secret offer that he had written in April that year to Eoka leader George Grivas, saying he was “prepared to go any place at any time you nominate to meet you. I would come alone and unarmed and would give you my word that for that day you would be in no danger of arrest.”

Grivas issued a defiant leaflet distributed by boys on bicycles. It described Foot as a ‘Trojan horse’ and the British plan as a ‘new monster’. He told Foot: “Chew your plan and swallow it,” the magazine wrote but added that conversely, the Greek government of Constantine Karamanlis dropped its longstanding demand for an advance promise of self-determination before entering any negotiations. Foot had also written a letter to an exiled Makarios offering to let him return to the island once violence ceased.

Despite his efforts on ending the Eoka campaign and bringing about independence, other historical writings confirm that Cyprus’ independence was not widely viewed as a cause for celebration.

In a paper in 2010 titled ‘Independence Day through the Colonial Eye’ academics Robert Holland and Hubert Faustmanm describe in detail what a “muted affair” it was compared to other British withdrawals such as in India. No royals, no members of the British parliament or government – only Hugh Foot ‘carrying the can’ on his own.

In his final radio address to the people of Cyprus on the night of August 15, 1960, the departing governor said: “What of the future? It is for you to answer that question. A few dismal commentators say that the people of Cyprus will destroy each other. They say that you will tear yourself to bits – Greek against Turk and Left against Right. There are a few who say that the Island will go down in a sea of blood and hate. It could be – but I don’t believe it. People who have been to the brink of hell don’t want to go over the edge. I know the difficulties and dangers as well as anyone, but I myself have faith in your ability, and in your good sense too. I believe that the forces of moderation and tolerance and compassion, and the desire to serve all the people of Cyprus well, and an overwhelming wish for peace, will prevail.”

In the words of the two cited academics: “Unfortunately for Cyprus the ‘dismal commentators’ would be proven right. In retrospect, Independence Day was not the end but just the beginning of another phase in the Cyprus problem.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences