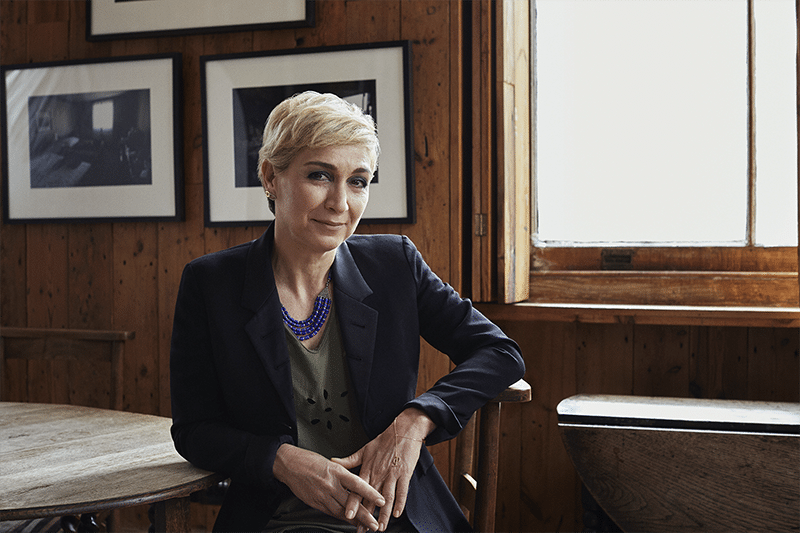

In the Queen of Money, THEO PANAYIDES meets a woman bored by the easy things, striving to overcome her impostor syndrome to shape change

It’s a strange thing about money. “Money is a tool for our wellbeing,” says a quote by Cleopatra Kitti on the Queens of Money website (queensofmoney.com), and it obviously is – yet we’re not taught at school how to handle it, we don’t understand how it works. Money, in fact, is political, closely allied to power and influence. Money belongs to the markets, the super-rich and the big corporations, those faraway forces ruling our lives.

Cleopatra launched Queens of Money – one of her various projects – just before Covid, seeking to empower women and improve financial literacy. It’s based on her own experiences, “on my learnings, and failings, in managing money, and driving my life in a direction I wanted to go, rather than being led by situations” – but it also gains its power from her status as an insider. Simply put, she comes from the world of money: the aforementioned faraway world, the corporate world, the influential world of technocrats and globalists.

Her LinkedIn page describes her as an “advisor to international organisations” – and she’s done (and continues to do) some of that, working in public relations and communications. She worked abroad for two decades – from the late 90s till her return to Cyprus in 2018 – her various big-name clients including even our own government, after the haircut in 2013, helping Cyprus “tell its story on the collapse of the economy”. She’s on the board of Eurobank Cyprus, a member of the Insead Independent Directors Network, a “philanthropist for peace” with the Brussels-based NGO International Crisis Group; the seed money for Queens came from UNDP, the United Nations Development Programme. Cleopatra Kitti knows her way around big organisations.

Her life was always (for want of a better word) privileged – but also more than that. She was raised in Nicosia “by a very loving, conservative family. My father and mother raised my sister and I [to be] very – proper, if I may say. The expectations were very clear: get good grades, be a good student. Having good manners. Being likeable. Don’t get off the beaten track.”

The family moved in prestigious circles. Her father Dinos served for two years as commerce minister – making for a happy symmetry when Cleopatra was headhunted by the Bank of Cyprus in her 20s (“when it was transitioning from a bank into a financial services group”) and approached by Charilaos Stavrakis, who later became finance minister. Needless to say, her parents were delighted by the offer: “They insisted that I go and work for a bank, so I can retire at the age of 60”.

Then again, that’s only half the story. For a start, she’s on the brink of turning 60 now (her birthday is on March 31) but has absolutely no plans to retire, her professional life consumed by another project called the Mediterranean Growth Initiative (MGI) – a machine-learning, data analysis platform for all the Mediterranean economies – as well as Queens of Money, a podcast called Koumanto Stin Tsepi Sou (‘Control Your Pocket’), and her various clients. In fact, she only stayed at the bank for a couple of years: “There was a lot of ‘You cannot do this’. So I said, I have to use my energy somewhere where I can do things”.

She always wanted more, that’s the point. “I always sought change… I was bored by doing the easy things.” The prim and proper upbringing didn’t really take – though she wasn’t a rebel in the sense of being belligerent, or anti-social. At school she was an average student but “very likeable”, a popular girl: “I didn’t make good grades, I was very socially involved. I was very sporty, very engaged in the social life of the school”. Cleopatra shrugs, trying to pin her teenage self down: “I just wanted to experience life… See places, do things, explore things”.

She studied in London, an executive secretarial course at St. Godric’s (she didn’t have the grades for Law, her first choice) followed by Business and Communications. Back in Cyprus, still in her early 20s, “I created a job for myself at the Hilton. I kind of walked into the general manager’s office and told him: ‘I think your PR is not as good as it should be, and I have some ideas’… He was very open to that, so I did a presentation”. She was with the Hilton for about five years, then Bank of Cyprus, then her own PR and public affairs firm which she founded with an American friend – then the Hilton flooded back into her life in a whole other way because she fell in love with the (new) general manager, a Dutchman at the tail-end of his posting. “And I had to make a choice,” as she says: “Whether to follow my heart, or keep doing what I was doing and stay here.”

Wasn’t she confident, though, marching into the manager’s office like that and staking a claim for herself? “In my impostor syndrome, I was quite confident,” she replies. “It’s bizarre.” Deep down, she was frequently beset by insecurity and self-doubt (she’s been in therapy, on and off, for several years), the bright-eyed façade hiding a deep-seated fear – impostor syndrome in action – that the ‘real’ Cleopatra was less impressive than the one people saw. Relationships, for instance, have always been the most important thing in her life and work, whether sociable teen or working with clients – yet it’s also true that, when she met the Dutch hotelier in her early 30s, she was already a divorcee with a toddler son.

Cleopatra was engaged at 19, to “a very lovely Cypriot man”. Their son Phivos (now 31) was born a decade later – but by then, the marriage was faltering. “I cannot speak for [my husband],” she says now, “but for myself, I think you begin to realise that you want different things in life. And I think no relationship stays the same forever.”

Her second marriage too ended in divorce, in 2009 – and by then, again, much had shifted in her life, the change from early 30s to mid-40s being almost as profound as the change from 19 to 29. Like she said, she’s always sought change – no relationship stays the same forever – or maybe it’s fairer to say that change is inevitable, “so we either shape it, or we allow it to come and find us – and find us, most probably, unprepared. So I’ve always been one of those people that tries to shape change, and lead it”.

Each of her four adult decades has been quite distinct. Her 20s in Cyprus, professionally confident but unsure in her marriage. (The divorce must’ve been quite a shock; nice Cypriot girls from good families didn’t divorce in the 90s.) Her “intense” 30s in various Hiltons – Turkey, Greece, Holland, Brussels, London – going back to school to study EU Institutional Relations while also raising a young son, then getting a job at APCO Worldwide where she stayed for 13 years. Her successful 40s, culminating in being headhunted by FTI Consulting whose then-chairman, Lord Malloch-Brown, was “looking to build a team to run a global-affairs practice” based out of Dubai. Her self-reliant 50s, launching her own projects (with mixed success; a consulting firm in Brussels “didn’t work out”), including MGI and Queens of Money.

It’s a strange thing about money. It’s so central to our lives – yet it, too, is subject to change, which is liable to find us unprepared. That’s especially true for women – not because they’re less savvy than men but because they’re paid less to begin with, and may end up trying to survive on a lower pension (unsustainably low, in Cyprus) unless they do something about it.

Cleopatra learned about money the hard way – and surprisingly late, given her years in the world of business. “I was earning a lot, spending a lot, and I had no savings,” she recalls. “I was transitioning out of my second divorce, which had many responsibilities: a lot of money-management issues to deal with, debt, property, getting my kid through university, looking after parents…” Like many women, she’d never really focused on personal finances, delegating all of that to her husband – “so when I divorced, I had to actually learn things from scratch. And it’s a mistake, we have to own our decisions… We co-create with our partners”.

That line – ‘We co-create with our partners’ – could be used for something else too, something dear to her heart in another way: the relationship between Cyprus and the EU, a big preoccupation since she returned to the island six years ago. “My goal is to be a bridge between Brussels and our region – because we’re a region that doesn’t claim as much as the Nordics do,” she explains. “We take passively the [EU] policies, without shaping policies.” It’s not just coincidence, or small-country politics – it’s a cultural thing: for whatever reason (probably centuries of history) we have low self-esteem as a nation, we don’t feel empowered. “We don’t have a culture to go and tell a story in Brussels.”

It all comes together: her own personal struggle to find inner confidence and conquer impostor syndrome, her journey to being in control in the world of money (“To understand how money works,” she says, “so you can make it work for you”) – and now the quest to make Cyprus more proactive, like she used to do with clients.

One might even discern a link to her upbringing, the adolescent thirst for experience and seeing the world – because that’s the basic problem in Cyprus, we’re stuck to ‘the beaten path’ instead of looking outwards and forming alliances. “We’re the only isolated market in the EU,” sighs Cleopatra. “Infrastructure-wise, but also outlook-wise. I think we think Brussels is far away.” She shakes her head: “Brussels is part of the way we regulate and shape our life, so we have to be more involved. Our voice needs to be heard… The future is regional. The future is not [about] making Cyprus even smaller”.

This, in the end, is perhaps the salient trait in Cleopatra Kitti: a certain expansiveness, a desire for more, a willingness to take risks – not out of recklessness but a kind of innate sociability, a thirst for excitement. She’s positive and “usually a giver, by nature”. She looks back – on the brink of turning 60 – without anger or bitterness, seeing the silver lining in her occasional failures and also “with a lot of respect for both of my former husbands, because they both added to my life – and to my son”. Her international career wasn’t driven by ambition, necessarily – more by following her heart, and because it seemed more exciting than staying in Cyprus. “To me, it’s not money,” she tells me. “It’s experiences. It’s getting to know people, understand cultures. Be a citizen of the world.”

Some would say she had no grand passions. Her life was (and is) mostly work, albeit high-powered work. (Any vices she’d like to share with the readers? “I love bread and cheese,” she replies, a little desperately.) She enjoys reading, exercising; she abhors social media. Her jobs were always busy, all-consuming. Cleopatra is a technocrat, her work with clients – especially when she worked abroad – involving wonky things like stakeholder maps, “a heat map of risk”, “a benchmarking plan”. It’s the language of the corporate world, the world of money.

And now? Life is good, if a tad less high-powered. “I do the things I enjoy doing, I work with people I respect.” She works from home, getting up at six to exercise for an hour (maybe yoga, or a walk in the park). She’s in a relationship, and surrounded by friends and family. Has Cleopatra Kitti figured out life? Probably not – just because that’s impossible. But she’s figured out money, and that’s a start.

Click here to change your cookie preferences