In a Colombian storyteller, THEO PANAYIDES finds a woman who has lived through drama – stepping over dead bodies on the way to school – but finds medicine in stories

It’s a three-act structure, like in any good story – though that’s not always true, stories are different across different cultures. Juliana Marín Fryling knows the score: not only is she a storyteller by profession – piling up a repertoire of hundreds of stories from the folklore, mythology and literature of her native Colombia – but she’s also been travelling the world for the past two years as ‘Achira Stories’, matching her stories to different audiences and trying to heal some deep-seated trauma in her own life.

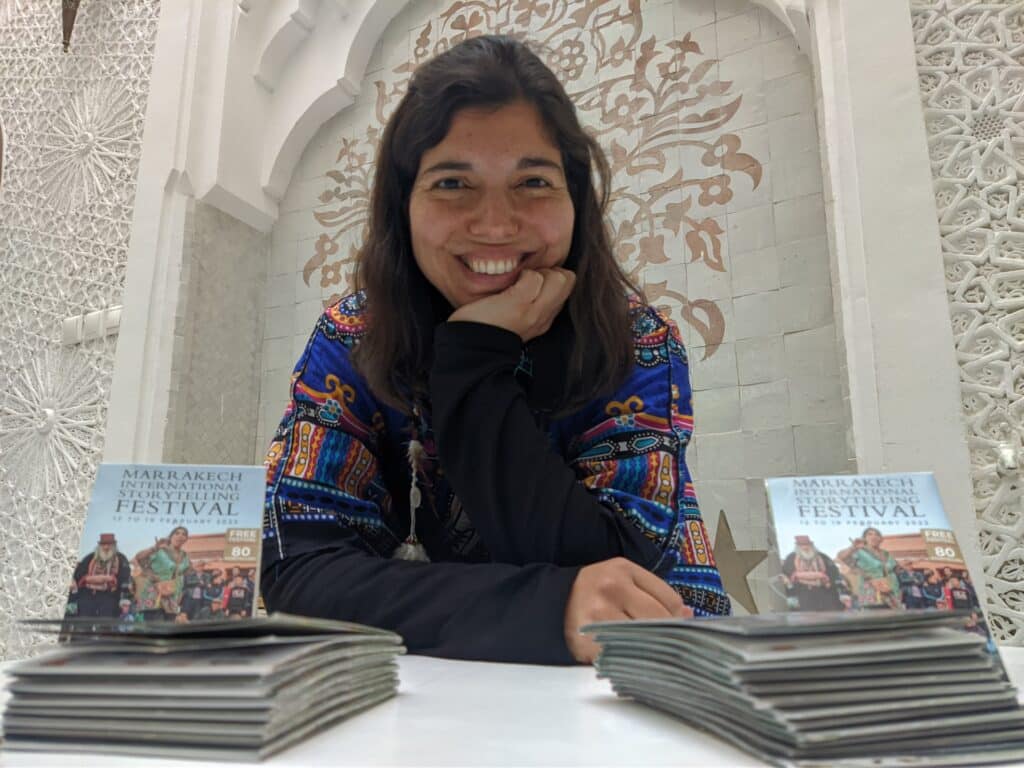

She sits across the table, flanked by her partner Julian, her freckled face sandwiched between a mop of blue-streaked hair at the top and a toothy smile at the bottom. The smile is impressively dazzling, beamed out apparently at will; I suspect it functions as a kind of social lubricant, for someone who travels a lot and meets a lot of people. She’s articulate, the flow of words effortless (did we mention she’s a storyteller?), her English that of a near-native speaker; Juliana’s mother is American (that’s the Fryling in her name), the daughter of Christian missionaries who settled in Colombia.

Juliana herself is 35 – which means she was five years old when drug lord Pablo Escobar was killed by police. This was in Medellin, the city Escobar ran “on the model of ‘silver or lead’: you take the bribe, or you take the bullets”, the most dangerous city in the world for many years, even after his death – but also Juliana’s own city (she pronounces it in the Colombian way, something like ‘Mevezhin’), the city of her birth and what you might call Act One (‘Childhood’) of her three-act life.

“Growing up, death was not something completely foreign,” she muses. “It was something that you kind of knew was going to get you eventually.” Juliana comes from an artistic family, and grew up surrounded by music, painting and sculpture. Her grandfather (not the one who was killed) was a noted sculptor; her childhood home was a kind of museum, filled with works of art – but that also made it a target. “My house was broken into 28 times when I was growing up.”

One of those times occurred when she was 17; two armed men burst in and herded Juliana, her mum and her two younger brothers into one of the rooms. “I was staring hard at one of them,” she recalls, thinking he looked familiar. Whether because of this – or because they were paranoid, or high on drugs – the men grew agitated, “and they told us to face the wall. And I knew they were going to execute us. I knew they were just going to shoot us in the head. And I refused to face the wall. I was not afraid at that moment… I remember looking at the guys and just grinning madly – and thinking ‘No. If you’re going to shoot me, you look me in the eye’.”

The robbers eventually backed off (obviously, or she wouldn’t be here); still, life was cheap in those days. One of her teachers at storytelling school – the Vivapalabra in Medellin, which she graduated from in 2015 – witnessed a literal illustration of that phrase one day, when a local drug lord and his friends were lunching at a hot-dog stand. Two teenage urchins, taking advantage of the hubbub, bought hot dogs and tried to sneak off without paying – “and the hot dogs cost 2,000 pesos, which is like 50 cents”. The drug boss calmly took out his gun and shot both youngsters in the back as they were fleeing, “then he goes over to the hot-dog seller and says ‘How much did they owe you?’”. He paid the man, the gang all finished eating like nothing had happened – even with the teens lying in the road, their blood puddling – “and eventually the guy rolls his cart away, so it doesn’t get dirty with 50-cent blood”.

‘But how?’ I ask, befuddled. How can people live in a place like that?

“You’ll get used to anything,” she shrugs – then gestures vaguely at the tables and chairs around us. “I mean, you get used to a divided city.”

Her point is well taken; we’re at Hoi Polloi in north Nicosia, minutes away from the checkpoint. Juliana was actually supposed to perform here last night – having already done a show at Prozak in the south – but had to cancel due to a problem with her voice. (She’s coughing a bit even now, but isn’t too worried; there are no more performances lined up until Morocco in April.) I’m a bit surprised to learn she’s been in Cyprus before, seven years ago – during Act Two of her life, what you might call ‘Discovery and Depression’.

Storytelling came into her life fairly late. She’d always loved words, and the original plan was to be a writer – “but writing is very lonely, and I’ve always been very much of a people person. So when I discovered storytelling I was like: ‘This is it. This is what I was born for’.”

It might seem an unorthodox choice of profession – but in fact Colombia, and Latin America generally, has a great storytelling culture, the oral tradition of travelling bards revived in the 70s as a subversive response to the various dictatorships bedevilling the region, using stories to say the unsayable. “Whereas in most countries people think of storytelling as something for children, in Colombia nobody tells stories for children. In Colombia, storytelling is a thing of the young and the angry… You come together to listen carefully, because they’re always saying something underneath.”

In the US, for instance, storytelling was “very family-friendly and kid-oriented”. Britain is similar, as she’s discovered on the current trip; British audiences “didn’t like controversial stories”, and were “outraged, absolutely outraged” when she told a love story – the romance between a tadpole and a caterpillar – with an unhappy ending. (Spoiler: a frog eats the butterfly.) Maybe it’s part of a general infantilisation – stories expected to be cuddly, like bedtime stories, and reconnect the listener with their ‘inner child’.

“I always try to find what people are hungry for,” explains Juliana. “And it does change.” When she performed in northern Cyprus, for instance, she recalls being swarmed by students telling her, “I want to be like you, I want to be able to travel – but I can’t disappoint my parents”. Family expectations weighed heavily (the isolated status of the north may also have contributed), “and the hunger there was for freedom”. In western Europe, on the other hand, there’s no real hunger for freedom – but “there’s a lot of hunger for connection. Because people are lonely, people don’t know how to relate anymore. In Colombia, there’s hunger for inspiration”. The country was stifled for so long, “you couldn’t see beyond that oppressiveness of violence that just blanketed everything” – but now things are better, and people look to stories to inspire them and push them forward.

She herself thought she was over her first-act trauma – especially when tourists started flocking to Medellin and she started working as a tour guide, telling stories of her city. (“I would say that stories have always been my medicine.”) But PTSD – which is basically what she was suffering from – is seldom so simple.

She travelled after graduation, as already mentioned; when she returned to Colombia, however, it was like all the bad memories had caught up with her – “and I suddenly found that I lost my capacity to tell stories”. She could still do it, mechanically speaking – but there was no joy, no spark. For years, recalls Juliana, she’d had “an almost mystical capacity… I’d see a person and a story would jump into my mind, and it was like ‘This is the story this person needs to hear’. And I’d tell them the story, and so many times the person would just suddenly start crying”. Now, inexplicably, that gift was gone. She stopped telling stories altogether for about four years, getting increasingly depressed – then Covid hit and, as she puts it on her website (achirastories.com), “I went to live alone in a cabin in the woods, with the intention to heal my soul or die trying”.

Thus begins Act Three (call it ‘Healing’) – a journey into self, not just telling stories to an audience but telling herself her own story. “Just close your eyes, ask [yourself] a question, and follow the story,” is how she describes her technique, though I suspect it’s one of those things that can’t be described, just experienced. “The cabin planted all the seeds,” she tells me now, sitting at Hoi Polloi with Julian beside her – but it took some fertile soil to nurture the seeds, the tour around the world (29 countries and counting) that’s allowed that new self to grow.

In early 2022, an invitation arrived for a storytelling festival in Morocco. “I hadn’t travelled for about five years – and I thought ‘Well, maybe I’ve healed enough. Maybe it’s time to bring the travelling storyteller back’.” Julian had just finished military service in Colombia (he appears to be a few years younger); she invited him along, as a friend and companion – but then something unexpected happened, they fell in love and decided to keep going.

From fear and hidden darkness in the violent city of her childhood to travelling “open”, trusting in the goodness of the world. The storyteller smiles, her three acts winding down to a happy ending. “So, it’s been amazing. It’s been magical… These have been definitely the best years of my life. For sure. By far.”

It’s not actually the end, of course – and indeed she’s brimming with ideas, including some surprising ones: “I’ve started moving towards motivational speaking”. Juliana actually comes off as much entrepreneurial as artistic, mentioning in passing that the storytelling world is rather niche and “bad at marketing”. It makes sense to use her knowledge of how stories work to motivate people, and hopefully make some money doing it; “This trip,” she enthuses, “has challenged and inspired me to dream bigger than I ever have”.

In the end, it was stories that healed her: memories of Medellin told to curious tourists, stories from Colombia (ghosts, shamans, love stories, a tadpole and a caterpillar) which she’s shared with the world, but also just the process of giving shape to life – understanding life – through a story. To gain perspective, explains Juliana, “and to step outside of your story, and become your own storyteller. Because if you’re in a story, you’re just being carried along. But the storyteller can make anything happen”. Stories have always been her medicine. She beams the toothy smile – a sign of joy or a shield against the darkness, who can say? – and strides into Act Four, and beyond.

Click here to change your cookie preferences