A few weeks ago, a column in Phileleftheros, under the headline “‘Islamic State’ in occupied area: Turkey’s plan for settlement and Islamification,” issued the following warning: “Ankara aims at the creation of an ‘Islamic region,’ completely Turkish, in the occupied area and within this framework it includes the strengthening of the Turkish population, the settlers, in combination with the Islamification of the occupied area. This strategy could be achieved ‘autonomously’ by the secessionist entity or through the annexation of the occupied area by Turkey.”

The article went on to inform readers that the Turkish Cypriot press placed the number of mosques at 213 and the number of people working at the ‘directorate of religious affairs’ at 240, of whom 120 were imams. More mosques than schools were being built while the imams had strong influence over schools and universities, the paper added.

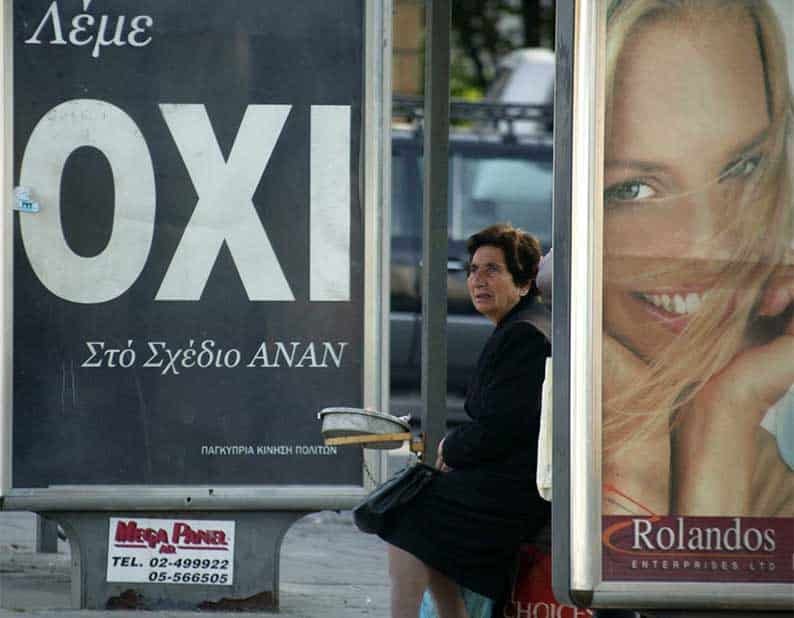

We mention the above as today marks the 20th anniversary of the Annan Plan referendum which 76 per cent of the Greek Cypriot population rejected. The Islamification of the occupied north and the possibility of annexation by Turkey that the columnist is so concerned about is one of the consequences of the vote against a settlement in 2004. Nobody gave a thought to the possible consequences of the ‘no’ vote back then as they were too busy celebrating the Greek Cypriot act of defiance.

If the plan, with all its weaknesses, had been accepted in 2004 the occupied north would have become territory of the EU like the rest of Cyprus and Turkey’s influence would have been drastically reduced. Ankara would not be able to treat the north as a Turkish province as it has done since 2004 and it would not have been able to flood it with imams with the aim of turning it into an ‘Islamic Republic,’ as the Phileleftheros columnist now fears. Even the flow of settlers from Turkey would have been stopped as there was a provision in the plan regulating the matter. Nobody knows how many Turkish nationals have settled in the north in the last 20 years but some Turkish Cypriots say they have become a minority.

Many of the people who voted against the plan were probably unaware of the consequences of rejecting a settlement as nobody spoke about them at the time. Even if these had been mentioned most people would still have been inclined to follow the plea of the president for a ‘no’ vote. There were consequences, however, that should have been obvious to everyone, like the opening of the fenced-off area of Varosha, which materialised a few years ago. Turkish developers have not moved in yet, but it is probably just a question of time. Everyone also knew that tens of thousands of Turkish occupation troops would stay on the island indefinitely if the plan, which provided for their withdrawal (only 600 troops would have remained as per the 1960 agreements) was rejected.

Twenty years later, the rejection of the Annan plan does not appear like the Greek Cypriot triumph it was celebrated as, at the time.

Click here to change your cookie preferences