The ancient art of contortion led one headstrong child out of her home nation to the circus and on to balancing business with wellness. THEO PANAYIDES meets her

For best results when reading this piece, I suggest you first go to YouTube and watch Otgo Waller in action – seeing, for instance, how she turns (or used to turn) herself into a kind of human package, resting her chin on her feet as other people do on their hands. We can talk about a ‘Marinelli bend’, but you really have to see it to believe it – a move that requires the performer to bite into a mouthpiece, bend their body into a kind of Z-shape (buttocks resting on head, legs extended), let go of the floor then “balance yourself on your teeth, jaw and neck,” as Otgo puts it. “That is extreme, yes.”

She’s not just the first contortionist I’ve ever met, but also the first Mongolian. Then again, there’s only a handful of the former in the world – and only three million of the latter, even though their country is bigger than France, Spain and Germany combined. She’s in Cyprus giving workshops, both ‘contortion workshops’ and on spinal wellness in general. If anyone’s suffering from spine issues, “wanting to take class or take advice, I’m here until May 4,” she informs me.

That’s quite an American touch, throwing in a plug for her services like that. Unsurprisingly, Otgo has lived in the States – Las Vegas, to be precise – since the early 90s, having first arrived with the famous Ringling Brothers B&B Circus.

She was 20 at the time (she’s now in her 50s), wide-eyed and fresh from a socialist country – though not entirely inexperienced, having spent her teens travelling behind the Iron Curtain with various companies. Contortion is officially an artform in Mongolia, and she passed the official test at the age of 11. “Then I got my diploma and I started performing, since I was 11 years old!”

Something quite important should be noted at this point. Contortionists have existed since ancient times, mostly as street performers alongside jugglers and clowns – but those ancient buskers suffered from a certain freakshow aspect, driven to perform by physical peculiarity more than anything. “At the time it was not an art,” explains Otgo. “It was more like double-jointed people, [or] people who have EDS. That’s a muscle disease – so people like that can fold themselves, and they don’t have pain.”

photo: by Christos Theodorides

Her own story is entirely different. She was born ‘Otgontsetseg Adiya’ in Ulaanbaatar, the capital, the youngest of six kids in an ordinary family with no showbiz links (her mum was a housewife, her dad a security guard for a big construction company). Otgo herself was a perfectly normal little girl – but “blessed with natural flexibility and talent” and blessed with something else too, strong-willed and independent-minded from an early age. “Since I was young, I was very determined. If I really want something, I just have to go get it. I was just born like that. Even my family never understood me, why I wanted to do this.”

Mongolia holds a special place when it comes to contortion, an acclaimed performer in the 1940s called Madam Tsend-Ayush having softened the old extreme style into something more graceful and sensual, more akin to art. “If you see my videos,” notes Otgo, “I’m not scaring people. I’m smiling. I go very slow motion, there’s a lot of, like, ballet movement involved”. That’s why the Mongolian State Circus ran a programme for budding contortionists – and that’s also why little Otgo saw a woman performing on TV (the woman who later became her coach), and became obsessed.

Her parents were opposed to a career in show business; the child insisted. The impasse lasted for a while – and indeed, by the time they agreed to take her for lessons she was eight years old, far too old for contortion. Kids usually start “between three and six,” explains Otgo, when the limbs are like rubber – yet she proved to be a fast learner, overtaking all the other students: “I learned everything within a year and a half. That’s very unusual”.

Once she got into the state programme she trained five days a week, albeit only three to four hours a day. Not only did the training have to leave time for school (though “I was not the best student”, in those days), it was also too strenuous to do for much longer. “You have to be strong to hold yourself up,” she explains. “Not just being flexible.” They’d do exercises to condition the body, “oh my gosh, there was so much… Hook-foot push-up, crocodile push-up, handstand push-up, handstand jump and different drills. There were so many things”. An ordinary push-up uses both hands and feet, but “we folded ourselves to push up,” scissoring the legs and basically “balancing your whole weight to do a push-up. Do you think that’s easy? That’s extremely hard!”

She also missed out on her childhood, I point out.

“Yes, you’re correct.”

Does she regret it?

“You know what? I never regret it… There are certain things I did miss out on. Y’know, playing with the other girls – going outside, just to have fun and play. Sleepovers with your friends. Those things I didn’t have. Do I regret it? Never. You know why? Because I started travelling all over the world.”

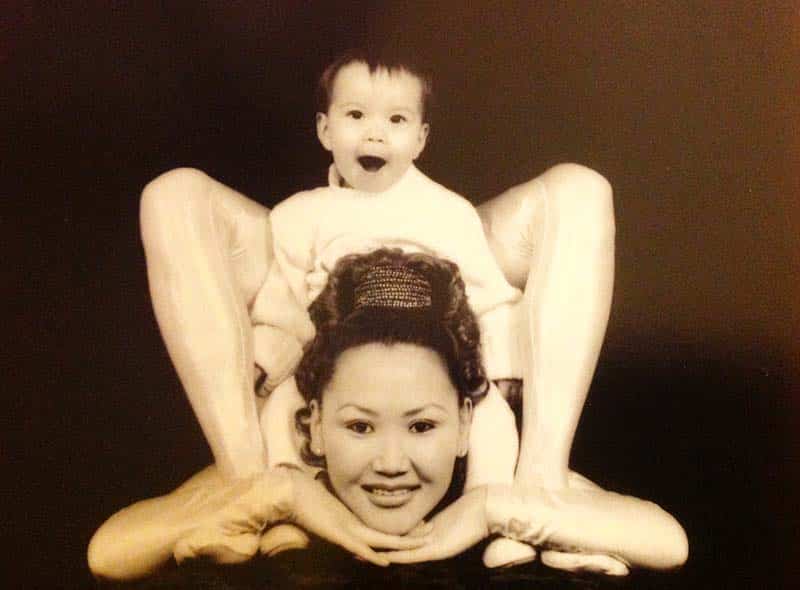

A younger Otgo with her daughter

Talking to her now, it can feel like a part of her is still that headstrong child dreaming big in Ulaanbaatar. There’s a girlish side – even now, despite her 50-something years. Her nails are painted alternately pink and blue, looking quite youthful, and the main Americanism she’s picked up over the years is an occasional incredulous “hello?” at the end of a sentence, making her sound like a stroppy teenager. Otgo is also very open and candid – so much so that it’s easy to forget how well-known she is, not just in her homeland (where she has her own Mongolian postage stamp!) but also in her adopted country. She’s performed live on national TV, including The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, and with the Cirque Du Soleil as well as Ringling Brothers.

She’s travelled all over the world, like she says – and in fact she keeps travelling, teaching workshops to ‘clients’ from all walks of life. Cyprus is a longer trip than usual (she came at the behest of Axinia Nazari, a student and fellow performer), but just in the next few months she’s headed to Austin, Denver, Utah, and Sedona in Arizona. This is part of the second act in Otgo Waller’s life – as teacher, author, businesswoman and health guru – which she’s fashioned with the same determination with which she sought out the first.

Again, this is all quite American, the idea of the self-made person – and you have to say she and the country hit it off right away. Back in Mongolia, “we didn’t have any information,” she recalls, “we were so brainwashed… So when I came to America I was culturally shocked. I’m not gonna lie, I was just like ‘Wow!’. This is how people are supposed to live! And I’m like ‘Omigod, my parents live in a crazy regime’. You had no rights. You had no rights to anything. The government owned you”.

Talent scouts brought her to Ringling Brothers on a two-year contract (they actually signed up four Mongolian contortionists for the three-ring circus, with Otgo and her partner on the centre stage). She travelled all over the US, living on a luxury train with dozens of other artists, “contortionists, jugglers, clowns, dancers, aerialists, magicians… You travel, you become family. Because you travel together for two years. You cannot hate each other, hello?”. Once her contract expired she moved to Vegas, looking to work in one of the casino shows. She also met a man, not a circus performer but a “very normal guy” – the first serious relationship of her life; that was Mr Waller from Chicago, and they stayed together for two decades (they have a daughter, now 20 and studying to be a nurse) before divorcing seven years ago.

I decide not to probe into why the marriage ultimately failed (though her open demeanour suggests she’d be willing to talk about it). Still, I suspect the common truism about people changing had a lot to do with it.

When she got married, after all, Otgo was a girl – a girl who could fold her body in amazing ways, to be sure, but a girl who’d grown up in a kind of bubble, unschooled in the ways of the world. That soon changed. “I started my business when I turned 32,” she recalls. She has a company, Flexible Body Art LLC, and a programme which is “US-trademarked and copyrighted, so I certify people to teach spine wellness”. She stopped performing in her early 40s, turning instead to teaching and writing. Her autobiography, Twisted Tales: My Life as a Mongolian Contortionist, came out in 2017, and is now on Amazon – but “I actually don’t want to sell on Amazon. I want to sell it on my website, and I’m actually looking to republish and redo a bunch of stuff. I want to move on with more projects”.

Otgo in nicosia, Photo by Christos Theodorides

Otgo’s a contortionist and businesswoman, using the drive behind one to power the other – though the curtain hasn’t fallen on her first act, far from it. She’s seen too many old colleagues go to seed once they stopped being flexible, not just ballooning in weight but developing heart conditions (the heart being suddenly forced to work harder in middle age), and she won’t let it happen to her. She trains four mornings a week, “stretches and conditioning” – and also starts her day with an hour of “Buddhist prayers meditation”, like her mum used to do. That may sound irrelevant – but in fact mind and body go together, the flow in the latter blocked by any turmoil or confusion in the former. “Peace is my priority,” she says. “I want to be leading a peaceful life.”

It’s a fine line, of course. Axinia, who’s hosting her mentor while she’s in Cyprus, is Iranian-Armenian – and now, right on cue, she appears, sounding deeply worried by what’s going on in our region (it’s the day of Iran’s retaliatory strike against Israel). How can you talk peace of mind, I ask Otgo, with the world going to hell all around us?

“It is,” she admits. But, again, it’s a fine line. “You know what, I don’t get bothered with these things… It’s not that I’m ignoring it – I just do my thing, and whatever I can do to help people. Doing my part. And then what am I gonna do? I’m gonna go out and protest, and stop the war? It’s not going to happen.” She volunteers once a month at an NGO called the Healing Hearts Movement back in Vegas, donating her time and money to help homeless people, orphans and so on – and of course she preaches the gospel of healthy living and spine wellness, bringing a measure of peace to everyone from models and athletes to a Yale professor and a CIA officer. ‘Doing my part’, like she says.

A younger Otgo

Some may joke about a contortionist performing moral contortions to salve her conscience – but in fact it’s fairer to speak of a person who was always very flexible still being flexible, or an artist whose art always depended on balance (sometimes with her teeth, like in the Marinelli bend) now seeking balance in her life as well. Otgo’s second book (she’s now working on a third) was called Flexible Spine, Youthful You, and it all comes together, her flexibility – also evoking a certain Zen Buddhist quality – and her sense of abiding youthfulness.

Otgo Waller’s signature move (I presume you can find it on YouTube) involved balancing on one hand with a candle in a bowl perched on her head, plus another candle (sans bowl) balanced on her foot. It all seems so complicated – yet her story, in the end, sounds quite simple, a girl in an isolated country going after something she loved (even though she was too old, and her parents objected), working at it doggedly and successfully, then shaping her life in a new way once middle age beckoned.

Was it flexibility, or the sign of a strong woman – or perhaps fate, or luck, or a readiness to go with the flow? Is it even worth arguing about? “The universe is amazing,” smiles Otgo sunnily. “How sometimes everything just works out.” Those YouTube videos are pretty amazing too.

Click here to change your cookie preferences