As a human rights lawyer Leto Cariolou is well versed in humanity’s messy, ugly side and nowhere more so than in the infamous Thanasis Nicolaou case

Leto Cariolou’s CV is easy to find. Go online – whether to her law firm in Cyprus, or Garden Court Chambers in London – and you can read about her years of representing applicants before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), her experience with the International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and so on. One thing, however, seems to be missing. I’ve looked around, I tell her – but you don’t seem to be on social media at all.

That’s true, she replies.

How come?

“Um… I guess I value my privacy.”

She does, and it makes for a cagey encounter. Lawyers and actors (as a hopelessly broad generalisation) often make difficult interviews, just because they’re so self-aware – and Leto is a human-rights lawyer, so she needs to be even more careful. It goes without saying that she can’t talk freely about individual cases – but she’s also reluctant to say, for instance, what she does to relax after a long day.

“Oh, I dunno… An occasional drink, here and there.”

Well, does she have any hobbies, or other passions?

“Yeah…” she says vaguely – then chuckles with a mischievous ‘Let’s not go there’ expression, taking a puff of her roll-up. “Nothing to report!”

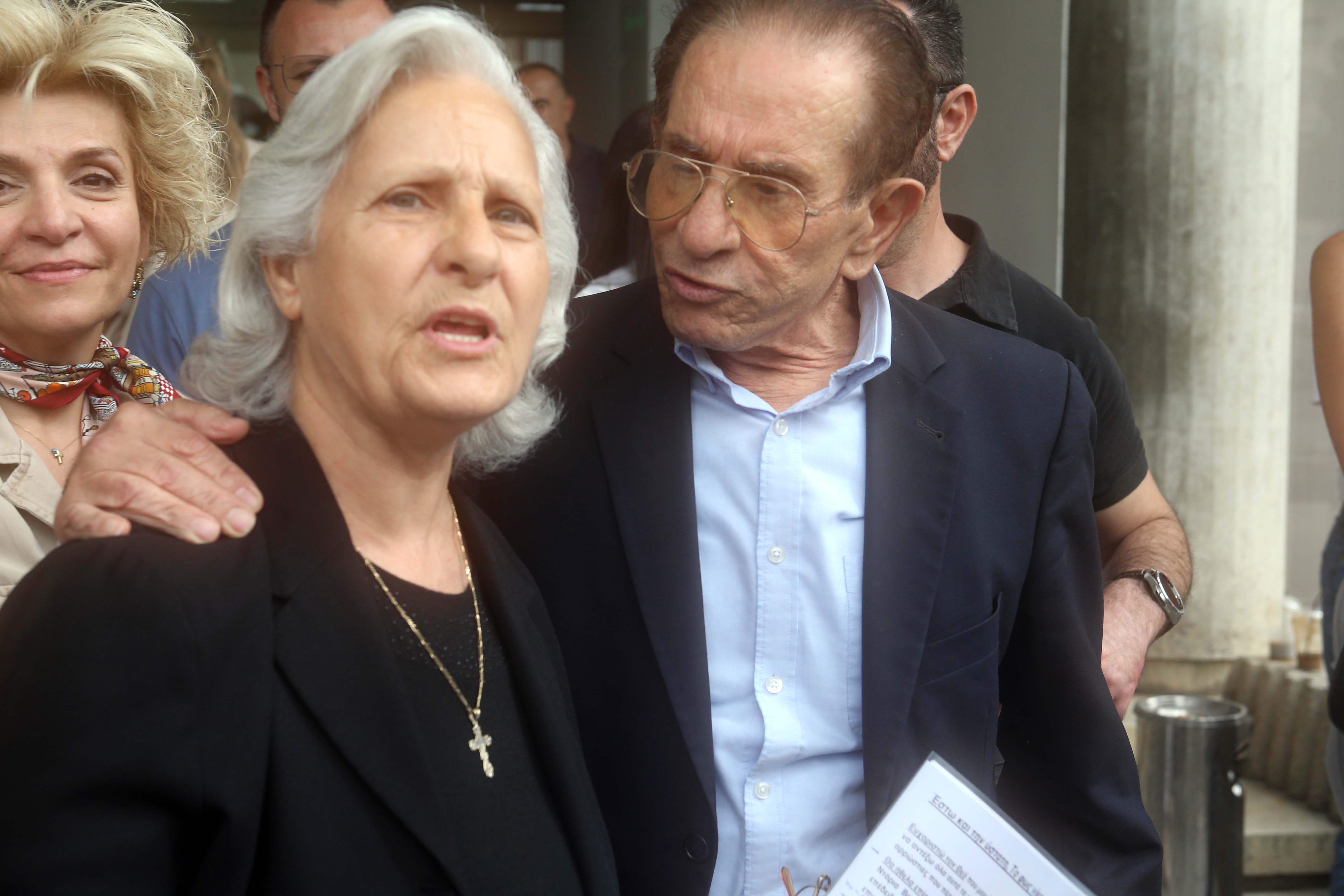

This makes her sound a bit awkward – but in fact the opposite is true. Her personal style is charming, bubbly, solicitous almost to a fault. Our setting is charming too, one of those high-ceilinged old houses near the buffer zone, with a staircase and small leafy backyard. This is both office and home, or one of her homes. Leto is based in The Hague, seat of the International Criminal Court (ICC), but travels “depending on court appearances and other work” – and started coming back to Cyprus about five years ago, when she also started working on high-profile local cases including the so-called ‘Thanasis case’.

We sit sipping coffee, the conversation punctuated first by the pealing of church bells, then the loud angry howls of someone down the road. (These old neighbourhoods harbour all sorts of people.) I’m a bit freaked out, but Leto takes it in her stride – a reminder that she’s seen and heard a lot in her career, having dealt with humanity in extremis. On a table is something she’s reading, The Lonely City by Olivia Laing. Further back, just behind her desk, is a photo she once took in Lesbos and likes to carry with her wherever she goes, as a kind of light-hearted reminder: a butcher’s shop called I Dikaiosyni, i.e. ‘Justice’.

Justice is indeed like a butcher’s shop, a meat market. What she does sounds noble – it is noble – yet it’s so often messy and ugly, dealing in human beings like so many pieces of meat. She must be very idealistic, I say at one point (stating the obvious, or so I think) – but Leto just shrugs. “I don’t know if I’m idealistic. I think I’m pretty realistic.” She gives a wry little chuckle. “But I do believe in principles.”

Realism is often warranted when it comes to human-rights law – a high-minded venture but also a minefield, prone to unintended consequences and ‘two steps forward, one step back’. Leto worked in Nicosia for a couple of years in her early 20s (she’s now in her mid-40s), at the Lellos P Demetriades Law Office, catching the tail-end of the Loizidou case – the various follow-ups to the landmark case at the ECHR, affirming the right of Cypriot refugees to return to their former properties. That was indeed a victory – but the later judgements muddied the waters, especially after the appearance of the Immovable Property Commission (IPC) in the mid-00s, and politics (she says) interfered in how the law was applied.

“We had our cases – the Greek Cypriot property cases in the north – frozen for many years,” she recalls, sighing unhappily, “and then [by the time] they were unfrozen, you had the IPC set up… And then our cases were dismissed, saying ‘You have to exhaust the new remedy’ – although there were clear problems with the remedy that was introduced.”

The Cyprus problem hasn’t really been a big part of her professional life – but Leto has some personal reasons for being unhappy with the way things turned out. The Cariolous are a well-known Kyrenia family, indeed her father Glafkos held the (ceremonial, but symbolically meaningful) post of mayor of Kyrenia for four years, from 2012. He was also “detained in Turkey, right after the invasion, where he was tortured,” she adds, almost matter-of-factly. “So that’s the background. I mean, it was always part of how we grew up.” ‘It’ is Kyrenia more than the torture per se (her dad never talked about the latter); then again, you have to wonder how much her father’s experience influenced her choice of career.

Still in her 20s, she left Nicosia for Strasbourg: four years as a case lawyer at the ECHR, then a decade at the ICC and its various tribunals and ‘specialist chambers’ – for Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, Lebanon, Kosovo. She’d always been drawn to such work, having studied international criminal law while at uni – at which time it was still in a kind of embryonic form. “I remember vividly that we were studying Nuremberg and WWII judgments, there was almost nothing else… A lot of it has happened in the last 25 years.”

Leto’s adult life, and her growth as a lawyer, has coincided with the growth of the (possibly quixotic) idea that war criminals can be held accountable, that war can be harnessed and made more civilised – though also, paradoxically, with a world grown increasingly volatile, the 21st century (so far) having been a time of ‘forever war’. The balance has shifted, she admits a little sadly: “I think there was a lot of optimism back then, which you don’t see anymore…

“I mean, what’s happened with Ukraine, and now Gaza, and Syria – it just makes you feel, what’s the point?” Even past successes seem diminished, the familiar dance of ‘two steps forward, one step back’. “When you see what happens in the Balkans… So much effort. Everybody who worked on those cases, so much effort went into it. So much effort. And then, what’s the point? Karadzic and Mladic are considered heroes, still, on the ground,” she says, speaking of the Bosnian Serb leaders now serving life sentences handed down by the ICTY. “Sometimes you wonder, does it matter. Not ‘does it matter’,” she corrects herself, “of course it matters for people to know what happened. But does it help, on the ground?”

Her own role was legal more than investigative – “I used to work for [judicial] chambers, which means we were drafting the judgements” – building up a record of atrocities, which is useful just in itself. Still, I suspect the past five years have been more rewarding – a time when she’s gone back to private practice, taking individual cases as well as continuing to work on “Strasbourg litigation”.

Why did she make the move? Was she burned out?

“Oh no – because it’s much more intense now!” she replies, laughing ruefully. We speak on a Friday; on Sunday she’s flying back to The Hague, not just to pick up her six-year-old daughter but also for final submissions in the case of Pjetër Shala, whose defence team she’s advising. Meanwhile, back in Cyprus, she’s waiting for the District Court of Limassol to decide in the case of Thanasis Nicolaou, the aforementioned ‘Thanasis case’.

That verdict was still unknown when we spoke (it’s now been officially established, of course, that Thanasis was murdered) – but the case has shocked the island, and Leto personally. What’s especially shocking is the way that “the fact of Thanasis’ murder is being – what shall I say, contested – and the manner in which it’s contested by the government, still”.

After all, the ECHR already found that the investigation of Thanasis’ death in 2005 was flawed, raising suspicions of a cover-up – “and now we have so much more evidence that this is a cover-up”. Yet the system continues to resist – and indeed what the case shows most vividly is systemic corruption, not just the proverbial ‘bad apples’ but flawed institutions (the army, the police, the law office of the Republic) purposely covering up for each other.

Thanasis, a soldier who was bullied to death, is obviously a victim; Leto is also representing the victim in a local rape case (now pending before the ECHR, following the attorney-general’s decision not to prosecute) and also assisted the victims of “a very serious maritime accident” in Ayia Napa last year. Pjetër Shala, on the other hand, has been charged with committing war crimes (in Albania in 1999) – and she also previously advised the defence team of Salim Ayyash, who was tried in absentia for terrorism. “I believe in fair proceedings,” says Leto when I point out the discrepancy. In other words, as already mentioned, she may or may not be idealistic – but she does believe in principles.

This, you might say, is the butcher’s-shop theory of justice, focusing on process and efficiency – as opposed to the bleeding-heart, protector-of-the-weak theory. She clearly does care about the weak, that goes without saying. Victims don’t get enough of a voice in Cyprus trials, she laments – and recalls the victim of the maritime accident trying to talk about her feelings in court, only for the judge to deem them irrelevant. “Come on,” she recalls thinking: “Of course it’s relevant. This is the main victim, and she’s describing how she felt!”

Feelings, and compassion, pervade her whole mission in life. That said, she also comes across as a very precise, fair-minded person, the kind who can see both sides, worries about being sloppy – “Don’t quote me,” she says more than once, when she’s not sure about some detail – and approvingly cites Blackstone’s famous dictum about it being better for 10 guilty persons to escape than one innocent to be falsely convicted. (No wonder she’s not on social media!) Her cagey side – the insistence on privacy – may also be relevant here, speaking as it does to a careful person as opposed to a sloppy, heart-on-sleeve one. Emotion underlies everything she does – but emotion should be part of ‘fair proceedings’, not just allowed to take over.

Take, for instance, hate speech – probably the spearhead of human-rights law at the moment, or at least the part that gets most publicity. Hate is an emotion – but it’s actually the ‘speech’ part that she finds more important. “I strongly believe in free speech,” she declares. “There’s no right not to be offended. Doesn’t exist… There is a right to offend, on the other hand.” Leto is very close to a free-speech absolutist, her legal publications including, in 2006, a paper called ‘The right not to be offended by members of the British National Party’, on the case of a bus driver who lost his job for being a member of the BNP.

There’s a line, of course. Incitement to violence (“if you call a group of people cockroaches that should be exterminated”, like they did in Rwanda) clearly crosses that line – but incitement to violence is already a crime, it doesn’t need additional protection. “But if I say I hate someone – then OK, I have the right to say I hate anybody that I do hate, right? I mean, free speech… That’s my personal view.”

But what if you hate a whole group?

Well yes, “that could be proof of discrimination” – but discrimination too is already prohibited, and of course it all depends on context. An immigration officer might be unfit for his job, if it were shown that he hates arrivals from a particular country – but there’s no reason why a bus driver, for instance, can’t also be a member of the BNP.

It’s all so slippery – much more than you’d imagine from social media. The world keeps making war, even as it also makes institutions to (theoretically) police war. Oppressors might morph into victims, if falsely convicted. One human right – the right to free speech, say, or perhaps my ‘right’ to write whatever I want – keeps bumping up against another, like the right of reputation or her right to privacy. “So what’s human-rights law? It’s just trying to find the balance, right? Between the competing claims.”

Leto Cariolou seems slippery too: charming yet reticent, hard to pin down. What drives her? Surely not money, or she’d have gone into company law. An urge to uncover the truth and make the world a better place? No doubt; but it’s not quite that simple. Maybe just a deep-seated need for justice – even just the messy, unromantic, butcher’s-shop kind.

“I don’t think I’m career-oriented,” she says, a bit surprisingly. “One thing led to another.” She shrugs: “I like interesting cases – cases that matter… I get bored easily”. The rest is silence, which of course is her right.

Click here to change your cookie preferences