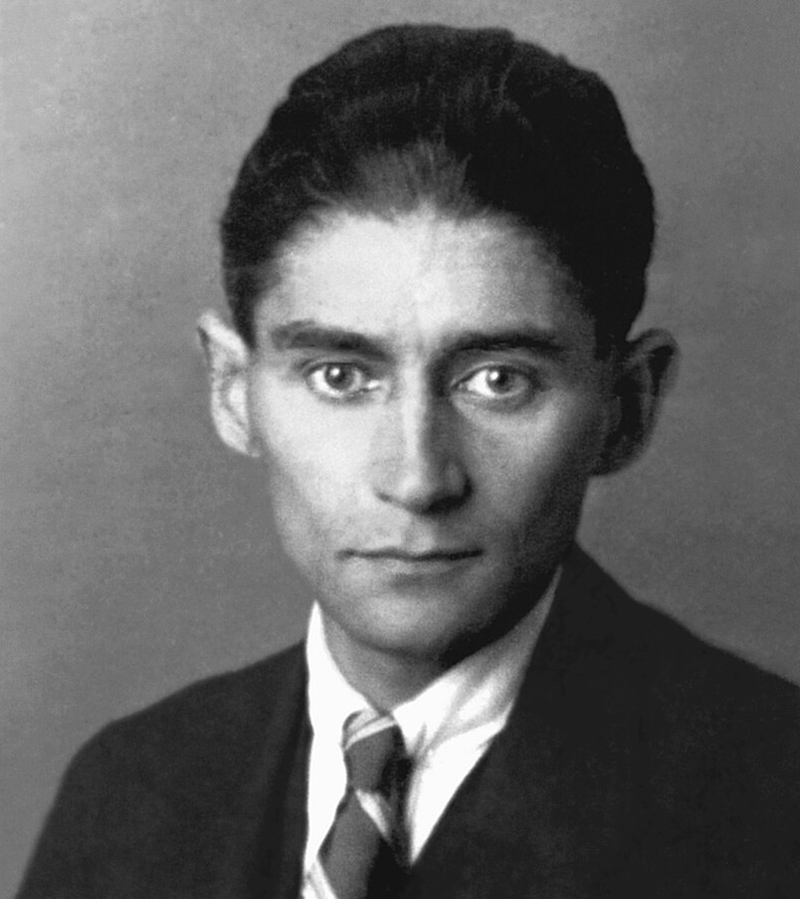

In the annals of literary history, few relationships capture the essence of unfulfilled longing and intellectual kinship like that of Franz Kafka and Milena Jesenská. As we mark a hundred years since Franz Kafka’s death, it feels fitting to delve into the epistolary romance that offers a profound glimpse into the soul of the 20th century’s most prophetic writer. For me, a lifelong devotee of Kafka, these letters to Milena are more than mere correspondences – they are the heartbeats of an eternal love story.

Kafka’s letters to Milena are a raw, unfiltered expression of his desires, fears and profound sense of isolation. “If you come to me you will be leaping into the abyss,” he wrote to her on June 13, 1920. Was this a warning, an ironic invitation, or an attempt to seduce by repelling? I often wonder. For months, letters, postcards and telegrams flew between Kafka in Merano, where he battled tuberculosis, and Milena in her Viennese home. Their correspondence began after a brief meeting in a Prague café, where Milena had expressed interest in translating Kafka’s works into Czech. For Kafka, a German speaker, her translations opened new vistas of understanding and connection.

Milena, a fiercely independent woman from a Christian family, was no stranger to defying societal norms. At 24, she had already faced ostracism for marrying a Jewish writer, Ernst Pollak, a friend of Kafka’s. In Milena, Kafka found not just a translator, but a kindred spirit who understood his deepest anxieties without judgement. For Kafka, who often felt like “the loneliest man in the world”, this connection was almost supernatural.

Is Milena Kafka’s Beatrice? In some ways, yes. But unlike Dante’s guide to divine enlightenment, Milena grounded Kafka, sharing with him her zest for life. Despite Kafka’s tendency to retreat into his “innumerable dens”, Milena tried to pull him towards the earthly joys she cherished. Organising a visit from Merano or Prague to Vienna became a Herculean task, each obstacle multiplying exponentially. Kafka’s approach-avoidance pattern left Milena in constant doubt, as he alternated between offering himself completely and withdrawing just as swiftly.

Kafka’s self-perception as a monster prevented him from fully embracing Milena’s love. His letters are rife with confessions of his “heaviness” and “dirtiness”, an obsession that precluded any physical intimacy. “I am dirty, Milena, infinitely dirty, that’s why I make such a fuss with cleaning,” he lamented. This self-loathing created a psychic catastrophe foretold in their letters. Milena’s inability to abandon her husband, Pollak, was a secondary issue; Kafka saw it as a convenient barrier to a love he felt unworthy of.

The culmination of their relationship came during four idyllic days in Vienna from June 30 to July 3, 1920. Kafka, momentarily free from illness, basked in happiness. Yet, this brief interlude only hastened the end. Their final meeting in mid-August in Gmünd along the Prague-Vienna line made the impossibility of their love undeniable. Milena would not leave Pollak, and Kafka could not escape his inner darkness.

Kafka’s resignation was poignant. He renounced the only person who had ever understood and loved him completely. “And perhaps it is not true love if I say that you are for me the dearest thing; to love is the fact that you are for me the knife with which I pry into myself,” he confessed. Kafka died in a sanatorium in 1924, his genius largely unrecognised.

Milena, however, lived on. She divorced Pollak, returned to Prague, remarried, and continued her life’s journey until her death in the Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944. There, she recounted her love affair with Kafka to fellow prisoner Margarete Buber-Neumann, who later honoured Milena’s memory by documenting their story.

As we commemorate Kafka’s centenary, his letters to Milena stand as a testament to an immortal love. For me, these letters are not just historical documents but echoes of a profound, personal resonance with the eternal human condition of yearning and connection.

Click here to change your cookie preferences