But families still waiting for justice seven years later

Judge-led inquiries that investigate events that cause serious loss of life are part of the procedural aspect of the right to life. States are obliged to protect the life of everyone within their jurisdiction, which is every state’s overarching substantive obligation under human rights law.

However, when a state fails to protect life, human rights law requires states to take procedural steps in order to find out what happened that resulted in the loss of life.

Hence the need to hold inquiries to find out the reasons why the state was unable to protect the lives of people within its jurisdiction. This is known as the procedural aspect of the right to life – the procedural steps states are obliged to do take when a loss of life occurs.

It is a parallel jurisdiction to holding a coroner’s inquest. In common law countries every time a person suffers a violent or unnatural death; or the cause of death is unknown; or the deceased dies in custody or other state detention, a coroner – who is a qualified lawyer – must set up an inquiry into the cause of death. The verdicts open to a coroner or coroner’s jury are: death by natural causes, suicide, unlawful killing, accident, want of attention at birth, industrial accident and open verdict.

In cases where a judge-led inquiry is designed to find out what happened and why people lost their lives, the coroner opens the case and then adjourns it until it merges with the outcome of the inquiry or a prosecution if there is one.

In Cyprus the Coroner’s Inquest is the usual way unnatural deaths are investigated. Not for the first time the police investigation methods in such cases have been criticised as unprofessional by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). In Nicolaou v Cyprus in 2020 in which a young soldier – Thanasis Nicolaou – died in highly suspicious circumstances in 2005 the criticism of the police investigation was that the police wasted the early stages of the investigation when matters were fresh by assuming it was suicide. The case has now been reopened but it is being argued to the ground by government lawyers despite the finding of a violation by the ECHR.

In the UK the inquiry on the fire at Grenfell in London in which 72 people perished in a towering inferno in 2017 reported last week. The judge found greed, dishonesty and incompetence at every level and made recommendations that the government promised it would implement urgently – especially those concerned with getting rid of other tower blocks still covered by inflammable cladding.

Exposing wrongdoing, however, is just one aspect of a state’s obligations. The second requires states to have in place criminal offences to deter offenders from endangering the lives of others through effective law enforcement and rigorous investigation of offences that may have been committed by those responsible for loss of life.

What the relatives of those who lost their lives really want at the end of the day is justice. And what they mean by justice is punishment of those responsible for the loss of their loved ones. Basically, they want those responsible to serve long sentences of imprisonment – it is revenge they want and revenge is very human.

Involuntary manslaughter is the only offence that fits the crime of someone who has foresight of serious harm to others if he acts in a certain way and carries on regardless in reckless disregard of obvious dangers. There are others but manslaughter is a versatile crime and has a wide punishment range.

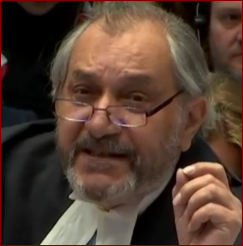

Of course, the nature of a criminal prosecution is different from an inquisitorial inquiry. Criminal offences need to be identified, and strong evidence of guilt needs to be found, and it is not always easy to prove guilt in criminal cases in which the standard of proof is beyond reasonable doubt. But to the families, wrapping Grenfell Tower in inflammable cladding was undoubtedly criminally reckless and they know the employees who made decisions about the cladding. As Michael Mansfield KC, barrister for some of the bereaved families, told the BBC some of those responsible are still in employment.

It is beyond belief how anyone with a conscience could have allowed a building 20 storeys high housing young families and children and elderly and vulnerable adults to be covered in highly inflammable cladding that enabled the fire to spread quickly when the cladding caught fire and engulfed the whole building, leaving those caught in the upper floors little chance of escape.

The procedural right to life includes a requirement to act quickly because memory fades and convictions become less likely.

In the meantime, what the Fire Service learned from Grenfell is that those who survived were those that got out of the tower quickly as they could see it was not possible for the fire to be contained; those who stayed put on the upper floors and waited for help to arrive were doomed.

Alper Ali Riza is a king’s counsel in the UK and former part time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences