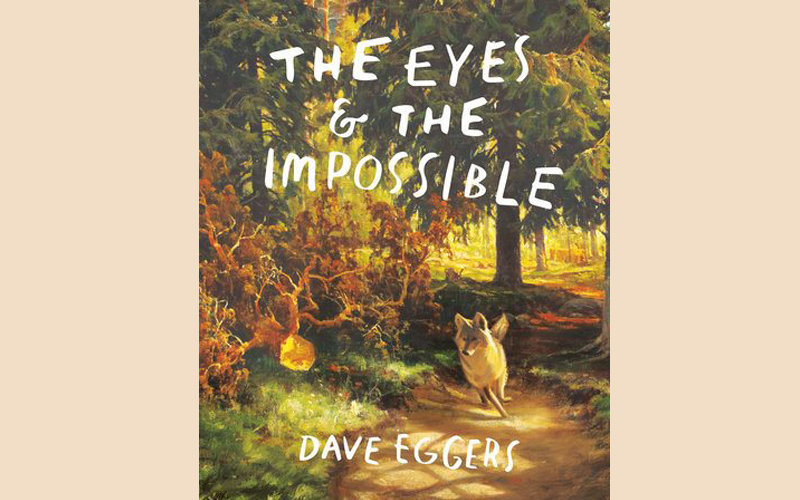

Dave Eggers has been a big name since the publication of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, which I saw around but never bothered to read since the title was so bombastic I needed more assurances of its sarcasm than were readily forthcoming. Anyway, all this is to say that I’ve managed to make my first Eggers novel his latest one, a book for younger readers about a group of very endearingly drawn animals living in a small island park. While The Eyes and the Impossible hasn’t made me regret my decision not to read any Eggers pre-2024, it certainly made me pleased to have spent some time in its company, and I suspect most readers of most ages will feel similarly.

There is a bit of bombast to get out of the way first, though. Eggers opens with a foreword declaring that ‘no animals symbolise people. It is a tendency of the human species to see themselves in everything… but in this book, that is not the case.’ Whatever, Dave. Not only does this fail to recognise the way in which young people suspend disbelief, but it also sets the book up for a senseless theoretical failure since a story written by a human in which animals speak to each other in English and engage in events along well-known narrative arcs can’t really avoid the taint of the human, so what’s the point of pretending it can? There isn’t any. I really wish the foreword didn’t exist.

Because the rest of the book is a pleasure. Johannes, our half-coyote-half-dog narrator is ‘the Eyes’ of a small island park that he estimates to be 10,000 miles long and 3,000 miles wide (one of the animals’ many loveable traits is their hyperbolic estimates of time and space). His job, in conjunction with his helpers (gulls, squirrels, pelicans and raccoons, but never ducks since ‘of course the ducks are morons’), is to report on human activity to the Bison, who are the keepers of the Equilibrium and the rulers of the park.

In the line of duty, Johannes develops a dangerous fixation with art, which ‘was like a crazy combination of actual things and made-up things and everything stuck together in this way that made no sense but seemed like the answer to a bunch of questions’ – and you will struggle to find a better definition! While the opening of new horizons lands Johannes in trouble, it also leads to his plot to free the Bison, and his eventual realisation that there’s more to life than our immediate senses and knowledge let us know. The plot is wonderfully madcap, and the realisation genuinely moving. Between the two, you’d need to be very bitter not to let the foreword slide.

Click here to change your cookie preferences