Ravaged by a hunger to ruin her own life

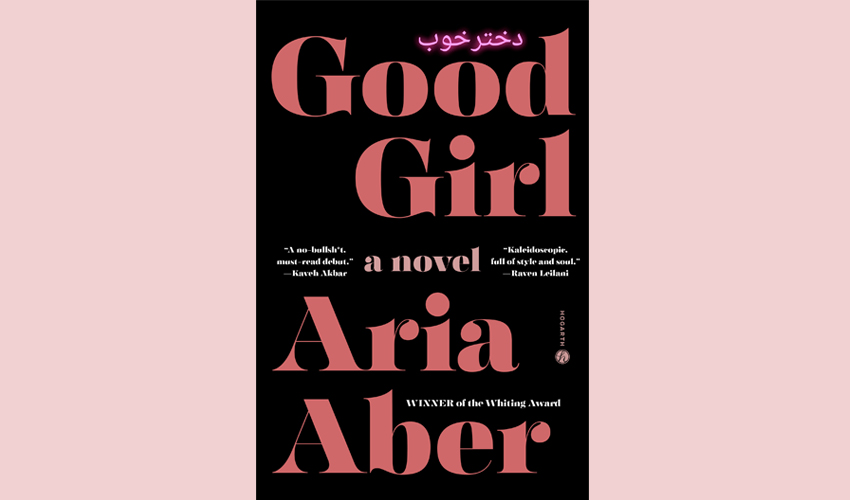

Another debut novel by a successful poet, and another opportunity to repeat my now truistic standpoint that one really can’t go wrong in turning the opening page by one of these talented code-switchers. The poet-turned-novelist this time is Aria Aber, whose Good Girl is a precise and moving exploration of a 19 year old daughter of Afghan immigrants in Berlin attempting to find a personhood that she can feel at home in, as a girl who feels at home neither in her skin, nor in her childhood home, nor in the escapist and elitist spaces that she tries or is forced to inhabit.

Nila is the name Aber’s ‘good girl’ chooses to go by, the removal of the final consonant that rounds out her real name, Nilab, a phonetic choice that echoes in the lies she chronically tells about her background, driven always by a nebulous fear consolidated by a post-9/11 reality in which her Berlin is rife with anti-Islamist suspicion, neo-nazis, and spurious philanthropists. Hating the life she feels ought not to be hers and the background she works so hard to fail to shed, Nila is ‘ravaged by the hunger to ruin my life’, so she plunges herself into Berlin’s underground and tries to drown out the internal noise with techno and drugs.

There is an inevitability to the reckless and self-harming choices we see Nila make, but as with any protagonist on an obviously negative spiral, the critical element is how far a writer is able to make us care about that protagonist. And Aber is extremely successful in keeping Nila resonant and idiosyncratic, despite the relatively well-worn path of her story. And in Marlowe Woods, the older American writer whom Nila meets in the novel’s fictionalised version of Berghain, and who immediately becomes the object of her desire, Aber creates the caricature of the kind of foolish choice a 19-year-old budding artist might make as their love interest, who is nevertheless potent enough to excite real disdain in the reader. He’s loathsome, and all the better for it.

All that said, there is ultimately too much Marlowe being pretentious and/or tedious and/or abusive, and too much drugs and techno. The novel’s finest moments occur in the interstitial and reflective passages where we learn about Nila’s family, or her doomed romance with another Afghan girl, or her days at the fancy boarding school she was sent to by her parents, or feel her grief at her mother’s death. Thankfully, there are enough of these moments to elevate the rest, and give the reader every reason to look forward eagerly to Aber’s next novel.

Click here to change your cookie preferences