How becoming a parent changes your life

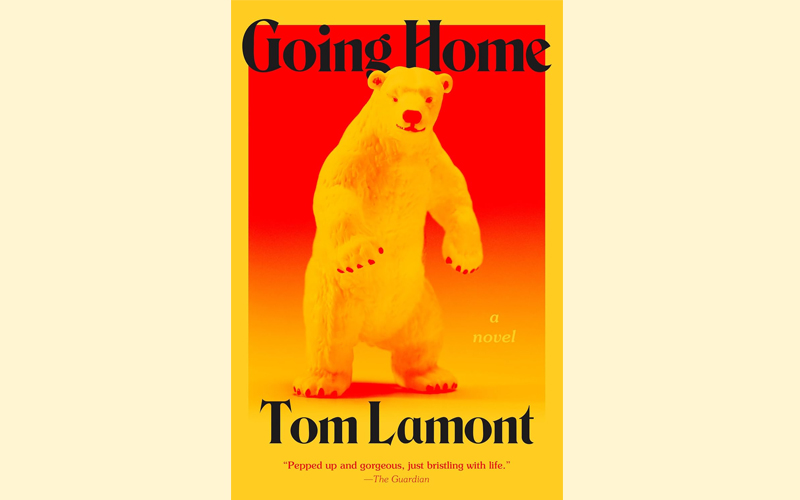

It is so clearly understood as to be barely worth saying that parenthood changes your life. And yet, every truism needs to be true, and every truth can be profoundly resonant if depicted with enough vividness to shock us out of complacent acceptance. Vividness is Going Home’s great virtue, and while Tom Lamont’s debut is not without some fairly significant flaws, the capacity to movingly render relationships between parents and children makes the novel vitally readable.

Téo Erskine thinks he’s made it out. That by getting hold of a car, a job and a flat in Aldgate, he is liberated from the close-knit Jewish Enfield community that he grew up in. He’s wrong. His dying father, Vic, remains in the flat they shared during Téo’s young life; the love of his life, Lia, is still there bringing up her two-year-old, Joel; and his best friend, the wealthy, charismatic, narcissistic dilettante, Ben, still orchestrates poker games that Téo can’t help but attend on his trips back to the North London borough.

The fragility of Téo’s illusions is made tragically clear when Lia commits suicide on a day when she has arranged for Téo to look after Joel. In the absence of a father (at least as far as Téo or Social Services know) or any extended family or suitable foster parents, Téo is given temporary guardianship of the little boy and has to move back in with Vic and learn the ‘repetition interspersed with the remarkable’ that is a life subordinated to caring for a child.

The novel is fundamentally about how Joel changes the way each of the central adult male characters view the world, from Téo struggling to accept his love for Joel and coming to realise too late that his father gave him more than he had ever realised or communicated, to Vic feeling reenergised by having a person in his life who ‘did not hold his age or his illness against him’ and who made him a figure of interest in the community again, to Ben finally learning to be a grown-up.

I mentioned flaws, and they all have to do with the Ben storyline. First is the enormous and frankly irritating plot hole that ultimately allows Ben to become one of Joel’s guardians, and the second is the rapidity and miraculousness of Ben’s reinvention which feels like an over-eagerness to neatly wind up the book. Thankfully, Joel, Téo and Vic have enough nuance and tenderness in their depictions, and Lamont’s Enfield is so brilliantly brought to life that the majority of the novel is utterly compelling. And for a debut, that’s not half bad.

Click here to change your cookie preferences