Ancient frequencies to combat the modern noise

By Dr Sophia Hadjipapa

As an artist and arts professor, the formal concepts of balance, harmony and symmetry have been integral to my education, practice and teaching. In my own artistic practice I have been drawn into a deeper exploration of these concepts, which has led me on a personal journey beyond the visual forms and towards inquiring into the philosophical and aesthetic sources of these ideas. In this article I briefly outline some of the striking parallels, resonances and also the distinctiveness in Eastern and Western thought and wisdom traditions associated with the concept harmony.

Harmony as an organising structure of a perfect world

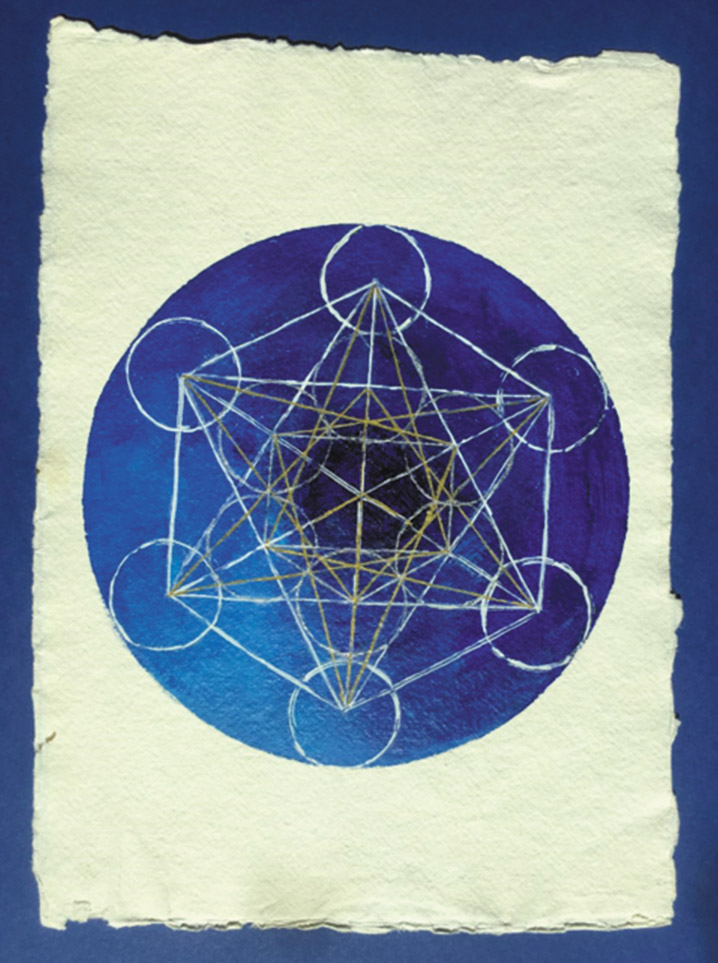

Through my investigations of symbols as vehicles of communication, not only between our fellow humans but also in ways connecting us with the transcendental, I started looking at ancient, simplified geometric forms, that seemed to encompass spiritual truths for people. In this work, predominantly researched in my project The Book of Hours, I sought to create a contemporary body of work, where traditions from around the globe render the desire to improve and transcend earthly existence, through archetypal shapes. I was particularly interested in geometry and symmetry and the notion that our understanding of perfection and beauty are part of an intrinsic harmony engrained in the fabric of this world.

That is how I got drawn to the work of Plato and more specifically his book Timeus. In Timeus, Plato refers to a “likely story” of how the cosmos came into being through the work of a divine craftsman known as the Demiurge. This Demiurge, being good and desiring the best for what he creates, uses the eternal Forms as a perfect model to fashion the physical world. Geometry becomes the very language and tool employed by the Demiurge to instil order and harmony. Plato links the classical elements (earth, water, air, aether and fire) with five regular polyhedra, also known as the Platonic solids. The foundation of this idea – that there is an inherent mathematical order and harmony in the universe – was a Pythagorean concept, upon which Plato built and systematized.

A fundamental principle underlying the universe

In Timeus, Plato also introduces the concept of the World Soul, an intelligent and living entity that permeates the cosmos and is responsible for its motion and order. The motion of the World Soul is described in terms of circles, the most perfect and uniform geometric shape.

And here is where it gets interesting. When I spent time in China I had the chance to delve deeper into Chinese philosophy and aesthetics and realised that the ideas around harmony and measure, are not only constituents of Greek philosophy, but in fact resonate with core principles of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism.

In Taoism, Chi (or Qi) is the fundamental life force or vital energy that permeates and animates everything in the universe. It is not merely a physical substance, or a simple form of energy as understood in Western science, but a more encompassing concept that includes aspects of energy, breath, spirit, and consciousness.

While in Platonism the World Soul is a cosmic principle that orders the universe, linking the realm of forms with the physical world, in Taoism “Chi” or “Qi” is the fundamental life force that flows through all things. Taoism emphasises living in accordance with the Tao, the natural way of the universe. I find it fascinating that both traditions address the idea of a fundamental principle underlying the universe!

Harmony and moderation in everything

Harmony and balance correlate with the idea of measure and moderation both in the Greek philosophy and Chinese philosophical thought.

“Παν μέτρον άριστον”- “Everything in moderation” is a famous maxim in ancient Greek thought. It encapsulates the emphasis on moderation, balance, and avoiding excess in all aspects of life, suggesting that virtue, well-being, and societal harmony are found in the middle ground between extremes.

Aristotle formalised this idea in his Nicomachean Ethics with his doctrine of the Golden Mean. He argued that virtue lies in the mean between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency. For example, courage is the mean between recklessness and cowardice.

These ideas had an influence beyond ethics and on aesthetics. The Golden Ratio, often observed in natural forms, could be seen as an example of the inherent order and a proportion that naturally arises and is pleasing to the human eye. Plato often links beauty to order, symmetry, and proportion. In the Philebus, Socrates states that “beauty and truth and proportion are the qualities which make a good mixture.”

Plato also stressed the importance of balance and proportion in the individual soul and the ideal state. Justice in The Republic is seen as the harmonious ordering of different parts, avoiding the dominance of any single element.

“Παν μέτρον άριστον” was thus considered to apply to ethics, politics, art, and even physical well-being, advocating for a balanced and moderate approach in all endeavours.

This idea appears to have parallels with the concept of the Buddhist Middle Way, which advocates for the practice of moderation, leading to wisdom, peace and ultimately spiritual progress. The Middle Way may be considered to guide all aspects of Buddhist practice, from ethical behaviour to mental cultivation and wisdom.

In Taoism living in harmony with the Tao – the natural order of the universe – is emphasised, which inherently involves balance and avoiding extremes. The Taoist emphasis on measure and balance may influence lifestyle choices, approaches to conflict, and the cultivation of inner peace and encourages a natural, spontaneous, and balanced way of being in the world.

In an interesting parallel, the ancient Greek thinker Pythagoras famously declared that “harmony sustains all things.” This belief extended beyond the celestial realm and viewed harmony as essential for the well-being of individuals, societies and their interaction with the natural world. The pursuit of virtue was intrinsically linked to achieving this inner and outer harmony, aligning oneself with the inherent order of the cosmos.

Similarly, ancient Chinese philosophy, particularly through the teachings of Confucius, emphasized the importance of living in accordance with the natural order. The “Six Arts” promoted a holistic development of the individual, fostering a sense of balance and integration with the world. Confucianism viewed nature not as a resource to be exploited but as a source of profound wisdom and a model for harmonious living. Observing the cyclical patterns of nature, the changing seasons, and the interconnectedness of all things provided a framework for ethical conduct and societal organization.

A path forward

As this short account illustrates, the ancient philosophies of Greece and China both recognised the fundamental importance of balance, virtue and interconnectedness for individual flourishing, societal well-being and our relationship with the natural world. These closely related concepts can all be seen to connect through the principle of harmony.

The distinct yet resonant insights from the traditions of East and West can and should become valuable sources of inspiration helping us face the challenges of today, respect our equally wise traditions and illuminate a path towards a more enlightened existence, individually and together.

Dr Sophia Hadjipapa is Associate Professor of Fine Arts at the European University Cyprus

Click here to change your cookie preferences