Political legitimacy in Confucian and Greek traditions

By Dr. Zeren Langjia

Is a ruler truly in control, or merely borrowing power from people? Throughout history, civilisations have devised distinct frameworks for legitimising rulers. Two influential traditions – the Confucian Mandate of Heaven (Tianming) and the Greek Will of the Demos – deeply tie legitimacy to how rulers treat their people. Yet, they rest upon fundamentally different principles, shaped by the contrasting worldviews of ancient China and Greece.

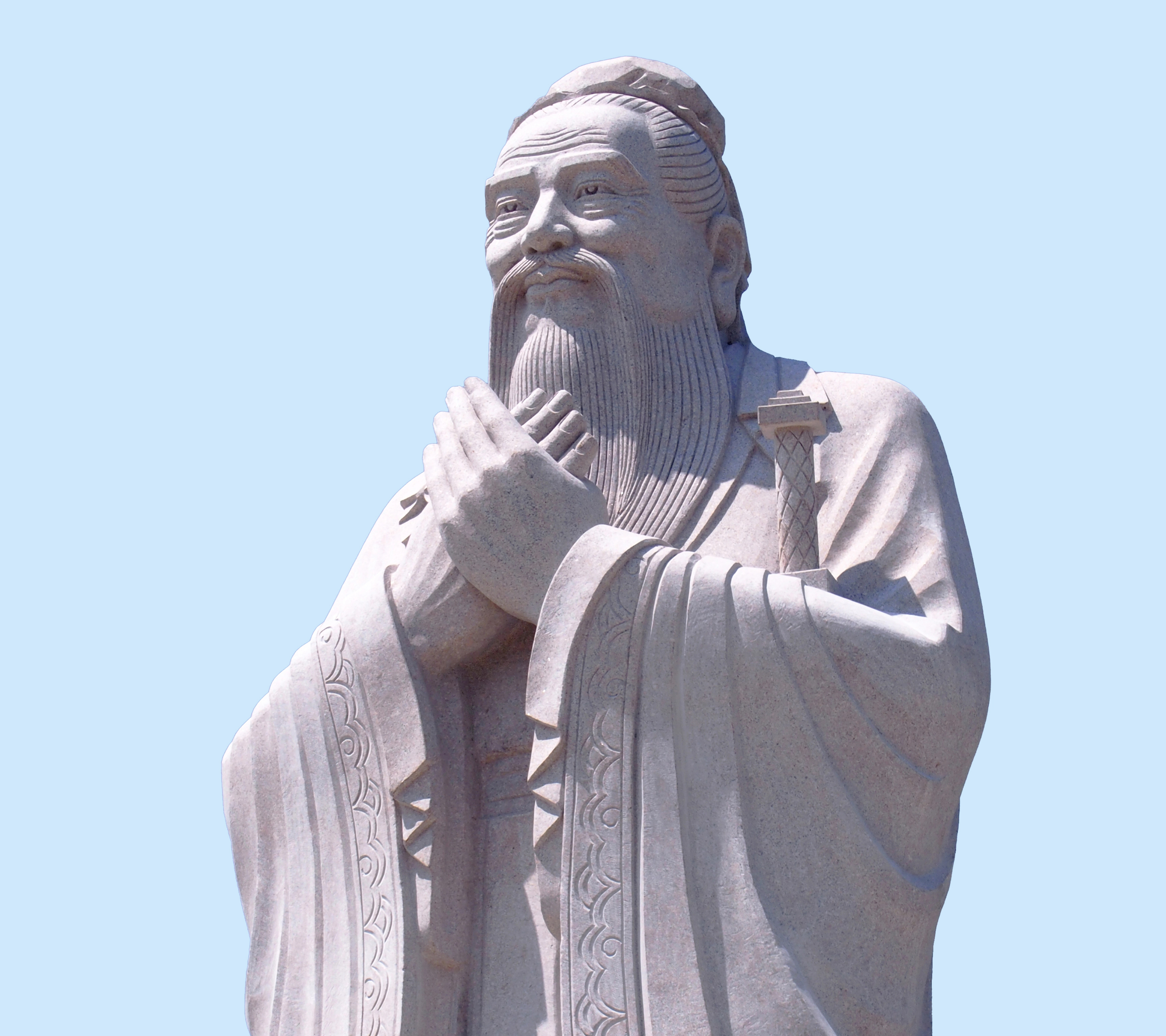

The Mandate of Heaven in Confucianism

In Confucian political ideology, Heaven’s Mandate is the foundation of legitimacy, placing authority in cosmic forces rather than human rationality. This doctrine emerged during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), when Zhou rulers justified their overthrow of the Shang by claiming Heaven had transferred its mandate to them. But the mandate is not permanent. Rulers must govern justly and for people’s material well-being, or risk losing it. Both Confucius (551–479 BCE) and Mencius (372–289 BCE) endorsed this argument.

Confucius believed rulers’ virtue legitimises their rule, but it’s the people who judge their benevolence in governance. A benevolent leader – embodying righteousness, propriety, wisdom and trust – earns loyalty, while a corrupt one loses heaven’s favour and invites rebellion. As he stated, “without the trust of the people, the government cannot stand.” He championed moral leadership, envisioning a hierarchical power structure where rulers prioritise people’s welfare, and in turn, people acknowledge their authority.

Mencius even asserted that “The people are most important, the state comes next, and the ruler is least important.” He argued that rulers must ensure economic stability, enforce just laws, and lead with virtue to maintain legitimacy. A ruler who commits inhumane acts loses the mandate and can be deposed, which actually echoes Aristotle’s justification for deposing tyrants. Mencius likened people to water and the ruler to a boat, declaring, “Water can carry a boat or overturn it,” underscoring that a ruler’s fate hinges on public support or opposition.

For centuries, the Mandate of Heaven kept shaping Chinese political thought, portraying the ruler as Heaven’s intermediary. A just ruler retained the Mandate and implemented benevolent governance, while failure to meet people’s welfare would render their rule invalid. Nevertheless, ordinary people were in no position to judge rulers.

The Will of the Demos in Greek democracy

Unlike Confucianism, Greek political thought was rooted in reason and the will of the demos. Athenian democracy, emerging in the 5th century BCE and marking a break from monarchic and elite rule, granted all free male citizens a direct voice in governance through the assembly (ekklesia), where they voted on laws and state affairs. Legitimacy thus stemmed from civic participation, with the people as the ultimate authority. Figures like Plato, however, doubted the masses’ wisdom. Socrates’ trial and execution exposed the dangers of mob rule, prompting Plato to reject democracy in favour of philosopher-kings, who were guided by superior wisdom and an understanding of the Forms, especially the Form of the Good.

Rulers, according to Athenian democracy, were chosen by people and held accountable to the demos. Pericles, in his Funeral Oration, warned that rulers who ignored people’s well-being would lose legitimacy. Aristotle distinguished between just governments (monarchy, aristocracy, polity) and corrupt ones (tyranny, oligarchy, extreme democracy), stressing that rulers must uphold justice or face rebellion. He cautioned that majority rule without virtue leads to instability.

Athenian democracy also grounded legitimacy in isonomia – equality before the law. While it excluded women, slaves, and non-citizens, the core principle was that legitimacy came from the demos through direct participation, not divine sanction. Rulers had to earn people’s trust and serve the common good, or risk losing power – a notion echoing the Chinese Mandate of Heaven.

Confucian and Greek political legitimacy: a comparison

Apparently, both the Mandate of Heaven and the will of the demos emphasise people’s role in political legitimacy, but they differ in their views on authority. Heaven’s Mandate is a moral and divine framework where legitimacy flows from cosmic order. A ruler retains power only if they govern virtuously and uphold people’s welfare; failures result in losing heaven’s favour and, ultimately, the throne. Confucianism emphasises the ruler’s virtue as the foundation of a just state, where a virtuous ruler uplifts society, and a corrupt one undermines it.

The will of the demos asserts that legitimacy comes from people’s collective will and direct political participation, not moral virtue or divine sanction. Athenian democracy stresses accountability, and authority depends on democratic processes and public support – rulers who lost trust faced removal, such as through ostracism. All in all, despite the differences, both traditions agree that rulers must justify their authority, whether through wisdom, virtue, or oracle.

Implications and modern relevance

Both traditions offer valuable perspectives on the ruler-people dynamic, but their implications for modern governance differ significantly. The Mandate of Heaven has shaped East Asian political thought for centuries and remains relevant today, as ruling parties derive legitimacy from their ability to sustain social prosperity and public welfare – echoing Confucian ideals of moral leadership and duty. The people-centred development philosophy, which prioritises “putting the people first,” views the people as the driving force behind China’s modernisation and defines governance as the pursuit of their well-being. It also reflects the continuity between China’s political modernity and its historical traditions.

In contrast, the will of the demos underpins modern democracies, where legitimacy arises from the consent of the governed. Elections and participatory institutions are meant to hold leaders accountable, yet challenges like voter apathy and political polarisation suggest that democracy must adapt to new realities. When designing the political system, the American Founding Fathers were already wary of direct democracy, recognising that the grass-root classes often prioritised immediate interests. French writer Alexis de Tocqueville shared the concern and warned of its risks – chief among them, the tyranny of the majority and cultural mediocrity.

If the great minds lived today, Plato might mourn that democracy, once a crucible of intellectual rigour, now falters under an uninformed electorate. Confucius, too, might be disheartened by the failure of universal education to cultivate civic responsibility. In response to such a problem, countries are seeking an inclusive system of governance that highlights the needs and rights of individuals while also ensuring that decision-making processes and policies are responsive to the collective will of the people. Yet one thing remains certain: a ruler’s power is never limitless – it always hinges upon the people’s judgment. •

Dr. Zeren Langjia: Institute of European Studies of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Click here to change your cookie preferences