Eastern and Western awakening of democratic thought

By Professor Xu Hong

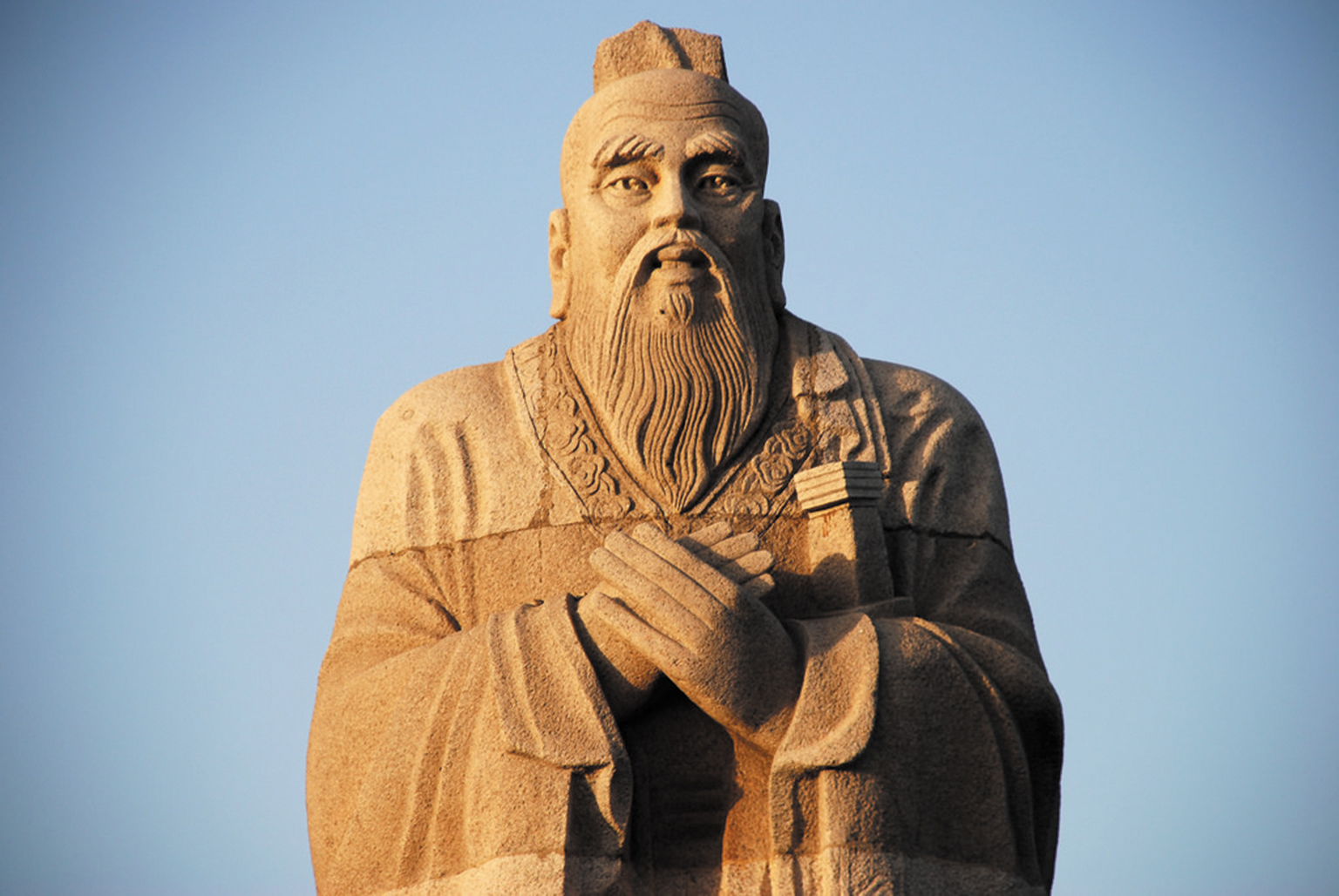

When discussing the challenges of modern state governance, people often overlook the wisdom that transcends time and space. The Acropolis in Athens and the Confucius’ Family Mansion in Qufu – both dating back to the 5th century BCE – embody the political philosophies of ancient Greece and China, respectively. Their enduring insights continue to enlighten us in addressing contemporary governance dilemmas. Exploring these twin origins of political thought and unraveling the parallel awakening of democratic ideas in the East and the West hold profound significance.

The initial resonance between Ancient Greece and China

In the 5th century BCE, within the Acropolis of Athens, 500 council members chosen by lot engaged in fervent debates over the laws of the city, their voices resounding through the foundations of the ancient polity. Meanwhile, in the East, Confucius journeyed across the warring states with his disciples, advocating the principle that “benevolence gains the multitude” – his teachings imprinted deeply upon the soil of Chinese civilisation. These two seemingly parallel historical moments converged on a fundamental question of political philosophy: human-centred governance.

In Ancient Greece, democracy manifested through citizens’ direct participation in civic affairs, embodying collective self-rule. In China, Confucianism emphasised the moral duty of rulers to cultivate virtue and serve the people – a principle resonating with modern democratic values of human dignity, rule of law, and civic engagement. Beneath the surface of power structures, the legitimacy of governance revealed itself as a symbiotic interplay between political ideals and practical administration.

The collapse of Bronze Age civilisations set the stage for divergent experiments in governance. Greece, with its maritime trade and scattered archipelago, fostered a culture of debate and contractual equality – grain routes along the Black Sea carried not just sustenance but the contractual spirit of equal trade. In contrast, China’s Yellow River floodplains demanded large-scale collective labour, reinforcing cooperation and coordination for survival. The Aegean’s fragmented geography naturally encouraged pluralistic deliberation, while the farming civilisation of the Central Plains yearned for stable, centralised harmony.

Here lay the primal stirrings of two governing paradigms: the Greek demokratia (rule by the people) and the Chinese mín wéi bāng běn (the people are the foundation of the state). Their simultaneous emergence, though worlds apart, marked humanity’s first conscious reckoning with a timeless dilemma – how to reconcile authority with justice, individuality with collective good.

The millennium dialogue between virtue and institution

Plato’s account of Socrates’ death in The Republic stands as history’s most piercing indictment of direct democracy – not merely a philosopher’s martyrdom, but Athens’ reckoning with its own political contradictions. As Aristophanes mocked the chaos of citizen assemblies in his comedies, Aristotle sought solution through his theory of mixed government: preserving popular participation while entrusting governance to the competent. This dialectical thinking on ‘quantity equality’ and ‘ratio equality’ coincides with Mencius’ thought of “sovereign power granted by the people.” Both traditions not only recognise the danger of unrefined majority rule, but also emphasise that the power of the rulers should be subordinate to the interests of the people.

When the Athenians expelled their political opponents in the square by the method of pottery exile, Confucius was teaching “harmony in diversity” beneath the Apricot Altar. His analogy of governance as “straightening warped wood” bound political legitimacy to moral exemplars, mirroring Plato’s philosopher-king ideal. Yet their remedies diverged: Confucianism wove an ethical ecosystem through rites and music, cultivating virtue as social glue, while Greece erected legal-institutional barriers to temper human frailty.

The Analects’ imperative to “elevate the worthy” and Laws’ mechanistic checks shared a goal – constraining power’s abuse – but mapped distinct paths. One sought to nurture noble character through education; the other to structure incentives and accountability. This ancient dialectic still frames modern governance: whether trust resides primarily in cultivated leaders or designed systems remains the unresolved question echoing across millennia.

The metaphor of water and boat: ancient wisdom in modern governance

Pericles’ funeral oration was more than wartime rhetoric – it crystallised the revolutionary ideal that “power resides in all citizens.” Like Confucius’ axiom “The people are to rulers as water is to boats”, it framed governance as a covenant between the state and its people. While Athens developed the ostracism system to curb demagogues, in ancient China, the Censorate (Yushi Tai) employed institutionalised oversight to scrutinise officials. Today, these ancient experiments in accountability resonate in modern democracies: independent judiciaries and free media now serve roles once fulfilled by the pottery voting papers displayed in the Acropolis Museum and the Han Dynasty bamboo slips unearthed in Luoyang.

The imperial examination system of Sui-Tang China – designed to dismantle aristocratic patronage – mirrored Athens’ abolition of debt slavery under Solon. Both sought to replace birthright with merit, though one tested literary mastery while the other empowered free debate. Similarly, Fan Zhongyan’s scholar-bureaucrat spirit of “not being thrilled or depressed because of external objects and one’s experiences” found its Greek counterpart in Plutarch’s portrait of Aristides the Just, whose integrity transcended factionalism.

These parallels now reemerge in Asia’s ‘meritocracy’ – hybrid systems blending Greek-inspired institutions (e.g. electoral checks) with Confucian governance principles (e.g. civil service examinations). The ostrakon and the keju exam, though millennia apart, shared a goal: taming power through structured competition. Their legacy endures wherever societies balance popular participation with elite competence – proving that ancient debates over virtue and systems remain startlingly alive.

The harmony of the drinking hall and the Imperial Academy: ancient pathways to people’s power

In the 21st century, we recognise that the symbolon (voting token) carried by Athenian citizens and the Zhou Dynasty’s wooden-clapper petition system served the same purpose: democratising access to power. When Mencius envisioned a society where “all are well-fed in years of plenty”, Athens had already granted political rights to its poorest citizens through Theseus’ reforms. This shared commitment to human dignity forms the double helix of democratic evolution – a genetic code linking antiquity to modernity.

Confucian governance, rooted in the principle that “the benevolent love others”, sought to elevate civic virtue through education and moral cultivation. Modern democracy, meanwhile, secures dignity through social welfare and public services. Though their methods differed, both traditions recognised a fundamental truth: a just state must nourish both body and soul.

Beneath these institutional parallels runs a deeper philosophical current. The conflict between divine law and human law in Antigone reverberated in Dong Zhongshu’s Three Disquisitions on Heaven and Man, each grappling with the tension between moral absolutes and political pragmatism. Likewise, Huang Zongxi’s denunciation of autocracy in Waiting for the Dawn echoed Aristotle’s warnings against tyranny – proof that critiques of concentrated power transcend cultural borders.

As technological revolution reshapes the global order and unilateralism disrupts international governance, the timeworn pillars of the Acropolis and the weathered steles of Confucius’ Temple in Qufu stand as transcendent coordinates of political philosophy. These vessels of ancient civilisational wisdom are far from dormant relics – they are cryptographic keys to modernity’s dilemmas. The Socratic interrogations on civic justice in Athenian Symposia, and the dialectics of “self-cultivation, family harmony, state governance, and world peace” in China’s Imperial Academy, converge upon one truth: genuine governance wisdom must be tempered through the crucible of cross-civilisational dialogues.

Today, as tariff wars degenerate into tools of ‘zero-sum games’, and as ‘my country first’ rhetoric tears at the foundations of multilateralism in the name of democracy, we must return to the wellsprings of civilisation for enlightenment: democracy was never the exclusive privilege of any single individual or nation, nor should it be weaponised to suppress the developmental rights of others. From the open debates of Athens’ Ecclesia to the intellectual ferment of Jixia Academy, the philosophers of antiquity demonstrated a timeless truth: a sustainable world order cannot be built upon unipolar hegemony, but must take root in respect for diverse paths of development. The resilience of civilisation lies not in the sharpness of weapons or the height of tariff barriers, but in its capacity to forge a more inclusive paradigm of global governance through dialogue and consultation – perhaps the most profound footnote to the vision of “a community with a shared future for mankind.” •

Professor Xu Hong: Chinese Director of the Confucius Institute at the Cyprus University of Technology

Click here to change your cookie preferences