A former sex slave tells THEO PANAYIDES she was molested as a teenager and branded a troubled kid. But, while laws are needed to stop trafficking, both sides involved in it need to heal

Talking with Timea Nagy is an experience; it could hardly be otherwise. For a start, she does it so well. She’s been the keynote speaker at hundreds of conferences, and is actually going to spend this entire day talking, giving me an hour by Zoom at 5.30pm Cyprus time – which is 10.30am in Ontario, Canada – before moving on to another journalist, then another.

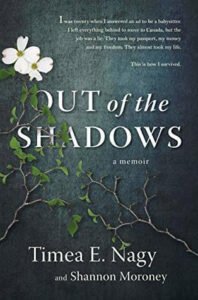

Her answers do occasionally sound a bit rehearsed, like something she’s previously said in a keynote speech or written in her memoir Out of the Shadows; “I was always a voice for the voiceless, even in the sandbox,” she recites at one point. Mostly, however, she’s frank, chatty, eloquent – and there’s something else too. Timea is an activist, and a survivor of sex trafficking; she was “abused on a million levels” for many years. That description makes one think of a certain kind of person – a righteous, understandably bitter person – but that’s not how she comes across. In a world where everyone’s a victim, she wants to be more than that. In a social-media-driven snake pit where anger and outrage are the currency of the realm, she invokes something far more precious: forgiveness.

An hour is barely enough to recount all that she suffered – yet she doesn’t wallow in the suffering, as if to say ‘Look closer; it’s complicated’. Take her childhood, for instance, in Budapest at the tail-end of Communism. A video on her website shows a childhood photo of a cute little girl in a white T-shirt with a Nesquik-bunny logo, flicking through a magazine with her little brother who’s smiling contentedly. Yes, they were poor, but she seems happy enough. Here’s her reply, however, when I ask about those years:

“I had a very difficult childhood. My mum was a police officer, my dad was a painter, like a house painter. They were very, very poor. Mum had undiagnosed mental illnesses and both of my parents had a problem with alcohol – but that was the 70s, everyone was drinking!” She gives a short, mirthless laugh. “There was domestic violence, there was all kinds of stuff. I was also very sick until the age of 10-11 years old, I was in and out of hospitals. At the age of 12 I was molested, and again at the age of 13… Father left at the age of nine, so I was raised by a single mother and my community. By the time I was 15, I was labelled as a troubled kid. At 16 I was already on my own, basically.”

The sickness she mentions was severe bronchitis, leading to lengthy stays in hospitals and sanatoria (“I actually died a few times,” she reports in passing). The first time she was molested took place in a crowded room, with family and friends present, “but no-one saw it because I was touched under the blanket. We were watching a movie at my neighbour’s house,” explains Timea, noting my startled expression, “the light was off and everyone was sitting there – my mum, my brother, my neighbour kids, my friends, their parents, we were all sitting around. The TV was on, because it was a movie night, and I was sitting between this couple – and he went under the blanket, and went in between my legs. And I had no idea what just happened. All I knew is that I felt so scared – and scarred, for life. And I left. I ran out. I ran upstairs to my apartment, and I washed myself for two hours until I scratched the skin,” she pauses, “you-know-where”.

There’s not much one can say after that story – and it actually happened again, at 13 (a colleague of her mum’s at the police station), and again at 15. “Unfortunately that’s a very common story. Girls are just being molested, sexually assaulted, harassed. If you meet three girls, one of them probably has an experience like that.” Her whole childhood sounds like a nightmare – yet here comes the twist because, as she notes, life is seldom just one thing. “I say in my book that when my childhood was good, it was really good. But when it was bad, it was really bad.”

A big factor was her mum’s mental illness (she was never diagnosed, but doctors have surmised she was probably bipolar with paranoid schizophrenia): “When she felt good, we had an incredible time. When she wasn’t feeling good, everybody had to pay the price”. That childhood photo isn’t a lie, per se. The bright-eyed little girl in the Nesquik bunny T-shirt may have suffered terribly, when the camera wasn’t looking – but she also travelled around eastern Europe (being a cop’s kid came with perks in Communist Hungary), went on summer holidays and exchange programmes, and was a model student, at least at first. It was only in her teens that she “became very promiscuous and sexual, and that was due to being molested – [but] the adults around me just labelled me that I’m a ‘troubled girl’. I was told that I’m probably gonna end up being a prostitute when I’m older.”

Timea was also (and remains) entrepreneurial – and the most surprising part of her early life is perhaps that she was something of a mini-celebrity in Hungary, around the time when she left for Canada. She and two friends launched a production company, “so I was on television at the age of 16, I was a VJ and we had a show for kids”, doing interviews and music videos. There’s a certain stereotype of girls who get trafficked – that they must somehow be adrift, uneducated, marginalised, the kind who’d go missing and no-one would notice – but, again, it’s complicated. Timea was “very established by the age of 19”, on her way to a solid career, had she stayed in Hungary.

Wait a minute, though. She was on TV, she was obviously street-smart. Wasn’t she at all suspicious of that newspaper ad?

For the first time she hesitates, unsure how best to phrase it. The short answer is that she needed money badly. Her mum was sick, the family was broke, “we were about to lose our house” – and besides, her contact mentioned possible jobs like cleaning and babysitting, all very harmless. The larger answer, however, is that she was traumatised, and traumatised people make bad decisions. One thing she’s learned in the years since – working with other victims through ‘Walk With Me’, an organisation she co-founded – is that most trafficked women (and men) have a past similar to hers, a past that “makes them so vulnerable that they don’t see the red flags” – or, if they see them, choose to ignore them, whether because they can’t face the thought of more bad stuff or because they’re desperately trying to escape, and hope it’s somehow “just going to work out”.

“I was picked up by two Hungarian guys and a Canadian man at the airport,” she recalls in the video on her website – and it didn’t take long for things to unravel. The babysitting job had fallen through, they said – but she owed them money for bringing her to Canada, “so now we need to get you another job”. Timea was tired, jet-lagged, in a new country; she spoke no English, and had no money. They took her to a motel, then to a nearby strip club where she was made to have sex with an older man – and there she stayed, as an ‘erotic dancer’ and sex slave, working 18-hour days and barely even allowed to eat, let alone leave.

Her brother back in Hungary knew something was up, but couldn’t get the cops to investigate. Timea herself, of course, was too cowed to do anything – “and then they constantly brainwash you: ‘Look, look how pretty [this other girl] is, she’s from Russia, she’s been here a month, she’s already made money to buy her own apartment’… And then they say, ‘You owe us $3,500, you need to pay that right now’. ‘I don’t have the money.’ ‘Well, I don’t want to disturb your brother back home – and you know what, we owe this money to Sasha, our Ukrainian friend, and he doesn’t mess around, so you need to help us out, otherwise your brother is going to be hurt’.”

Strangest of all was the sense of denial that kicked in after a few weeks. “I’m not a prostitute,” she insisted to herself. “I’m in a bar. I’m in a club. It’s fancy, everyone’s so nice… I’m not a prostitute, and they’re not my pimps. But of course I was a prostitute, and of course they were my pimps”. By the end, when Timea finally escaped after three months with the help of a security guard and a Hungarian stripper, “they were the ones who approached me and told me they think I’m being trafficked, and they’d like to help”; she herself had become “a zombie,” she says in the video, unable even to discern that “something is so wrong here”. Many of those girls stay for years, often becoming drug addicts. In the end, an abuser’s greatest weapon is the vulnerable victim’s passivity and low self-esteem, the way they can end up convincing themselves that it’s not so bad, or perhaps it’s their own fault.

Even more controversially (though it shouldn’t really seem controversial; it’s just human nature), Timea doesn’t see her abusers as evil, necessarily. “My Canadian handler was a very nice guy – and a pig at the same time. He would molest me, rape me, touch me – but he did it so gently, and he never hit me, and he bought me food. And he cared about, if I ate today. So it’s not black and white, and it’s not that simple.”

None of this is to excuse slavery and trafficking, of course (that goes without saying) – but it does tie in with how best to combat it. The most uplifting part of Timea Nagy’s advocacy work is perhaps that it’s not about censure, it’s about healing: “That’s my approach. Everyone needs healing, both sides”. After all, she notes, “it’s not good for the boys” either – meaning the clients who visit sex clubs, and keep the whole system running. “It’s just not good, it’s degrading. But there’s no way out, because this is what we’ve been doing for so long… So I’d like to establish that message for the next generation of activists – to say yes, laws are important, but we need to go to the root causes and we need to heal society. We need to heal the traffickers, we need to heal the victims. Because, if you take a trafficker and you imagine them when they were five years old – do you think they dreamt about becoming a trafficker?”

Laws are needed too, of course; the sheer volume of human trafficking and forced labour is bigger than ever, despite the many NGOs and wealth of resources. “There are 40.85 million people in slavery today,” she quotes grimly. That said, there were even fewer laws in Timea’s time, and not much she could do once she’d escaped (her traffickers were never convicted). She didn’t even go to the authorities for two years, afraid of being deported.

“It took me about 12 years to rebuild my life,” she recalls. She stayed in Canada, but still spoke no English and had no papers. “I worked on four, five, sometimes even six jobs under the table… I was working in an elderly home, I was cutting nails, I was cleaning, I was working in a strip joint as a waitress and bartender.” She moved house about 50 times and walked to work in the brutal Canadian winter, feeling the freezing slush through the holes in her boots. She spent her 20s “just surviving,” as she puts it – then met her husband, a professional actor who brought two stepchildren, a touch of showbiz to recall her old TV celebrity (the couple recently launched a YouTube channel called Now You Know Talk Show; “My old skills are kicking in!”) and, most importantly, a shoulder to cry on when she has bad days, which she does sometimes.

Partly it’s survivor’s guilt, partly just the demons of her past – but “I can get triggered, definitely”. Often, she doesn’t even know what the trigger was. A few years ago, she and her husband were at the cinema watching Woman in Gold with Helen Mirren, a movie that has nothing to do with trafficking – but, at the scene where the heroine goes home after many years, “I started crying so hard. I had to run out of the movie theatre – and, in the middle of the parking lot, I had one of the biggest meltdowns in years. And my husband just held me, he stood there, he just waited and waited, and I was bawling my eyes out.”

So much has happened to Timea Nagy. She reels it off, as she’s done hundreds of times before – yet it doesn’t feel mechanical, mostly because her message is so warm and compassionate. Her hobbies are cosily domestic, cooking and baking and “home décor” (she also has three cats), and her worldview is equally cosy. Have her travails left her with a cynical view of humanity? She smiles down the transatlantic Zoom connection: “I actually have a huge love for humanity. Because I know we can be very bad, and very dark – but when we’re good, we are so beautiful!”. Anger is a choice; so is forgiveness. “The guy who trafficked me to Canada, I could be mad at him my whole life if I choose to. Or I could thank him for bringing me here, so I can meet the most beautiful man and marry him.”

Timea looks at me calmly: “The choice is mine”.

Step Up Stop Slavery was set up to help combat human trafficking and modern slavery in Cyprus. The NGO will open the island’s first survivor support centre, offering holistic legal and therapeutic support to survivors by its team of trauma informed experts. The NGO will also roll out trafficking awareness and prevention training programmes for professionals and schools across Cyprus

Click here to change your cookie preferences