A street art project in the north tells the tales of people who have coloured the city. AGNIESZKA RAKOCZY meets a man determined to use art to reach people and bring them together

With the Ledra Street (and other) crossing open again after more than 15 months we can finally walk once more around the old town of Nicosia in its entirety, remembering all the good and bad that has happened within its walls. And when you cross to the northern part of the city, keep in mind that these walls can and will literally talk to you about an eventful history and the people who have lived and worked within them.

Cigerci Ahmet, Saffet Anibal, Huseyin Caglayan, Resa Budak, Ali Dayi, Naciye Nene, Asyamiz, Arif Abi, Ibrahim Abi, Sefik Abi – unfamiliar names perhaps to most Greek Cypriots but ask anybody in the north and they will regale you with stories.

Cigerci Ahmet was a renowned fried liver seller in old Nicosia, as famed for his juicy language as for his savoury meat treats. Anibal had the best kebab. Huseyin Caglayan’s restaurant gave its name to a whole neighbourhood. Resa Budak made the best ice cream. Ali Dayi was a blind fruit and vegetable seller. Nacije Nene took care of the Yediler Tomb (Tomb of Seven Brothers) in the Karamazanzade quarter. The list goes on.

“In total we planned 11 portraits. One still awaits completion. We got delayed because of corona but now it will happen very soon,” Dervish said.

“We want to do more but the last in this series will be of Naciye Nene, who died at the age of 92 in 2019. She stayed in the old town even though all her family moved out because she wanted to take care of this Ottoman tomb. And she did. We all knew her. If she got angry with somebody she used to curse like crazy but if you found her on her good day she was the sweetest Cypriot grandmother you could imagine. Every day she would come to the Bandabuliya to do her shopping. In this way nothing ever changed in her life. That is why we want to do her portrait too – because of the good example she has set for us. She held to her values all her life.”

We are sitting in Hoi Poloi, close to the Ledra Street crossing, just a couple of metres from where the Naciye Nene mural will soon be painted. Our conversation is repeatedly interrupted by one or other of the many passersby. Everybody here knows Dervish and many, especially kids and their parents, greet him respectfully as ‘hoca’ (master), a title commonly used to address teachers. Forty-one-year-old Dervish with his dreadlocks, tatooes and baggy trousers doesn’t look the part and admits he is not actually “very fond” of being addressed with such deference.

He and a group of like-minded creative and artistic people go jubilantly about their work, dedicated to transforming this old town. Not for them the encroaching skyscrapers that lock in and shrink the city horizons. Their vision is to expand the view from within. Newcomers perhaps but futurists too, who want to preserve the old town’s past while readying it for the future yet doing so without changing its character.

“People love the Good to Remember project because they knew and recognise all these characters we are portraying here,” says Dervish.

“Everybody had some experience with them. Everybody can tell you some stories about them and what they meant to them. Let’s take Ali Dayi, the blind fruit and vegetable seller. Every day he would go to the Bandabuliya, chose his vegetables and fruits and then sit in front of the bazaar selling them. Can you imagine the relationship betweeen him and his buyers? It was all formed on trust, they protected him. But he would never accept any help from anybody. These are memories we are trying to retain.”

He laughs with delight as he points out the project’s very Cypriot character.

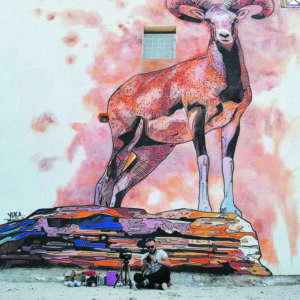

Anibal’s portrait in Caglayan park

“You know if it was in Italy, we would paint portaits of doctors or politicians on these walls. But here we just paint our neighbours.”

Dervish is openly and unabashedly in love with Nicosia. From the moment we sit down to talk he makes clear he cannot imagine living anywere else. “I love this place, this country,” he says.

“I did my MA in the UK but didn’t want to stay there. Then I went to do my PhD in the United States. I landed in San Francisco, the university was in Florida. Both places a dream to live in. But I come from a place like this… and the speed of life there was too fast. There was no connection with other people. I looked around and realised I didn’t want to do it so I left.”

What was he planning to study in the US, I ask, and Dervish laughs.

“Well, it was a Cyprus classic – conflict resolution. I knew it was a cliche but on the other hand I believed I could do something different with this subject… Then I realised it would be too much concentrating on just one thing. And all my life I have been doing many different things at the same time. I was playing basketball but also doing other sports. I was a folk dancer and carried eight or nine glasses on my head while dancing but then I moved on to Latin and ballroom and hiphop. I have never been afraid of big challenges but this PhD stuff, I realised I really was not looking forward to it…”

This however didn’t mean that Dervish turned his back on conflict resolution. A self-described “problem solver who likes to see things being put straight and sorted out”, he determined he would find “another way of doing things”.

His least favourite expression is ‘Cyprus problem’. The truth is “there is no Cyprus problem, it is only politics,” he says.

While struggling to find exactly what it was he wanted to do he came across the PeacePlayers, an NGO that “uses sport to unite, educate and inspire young people to create a more peaceful world”. Here was an opportunity, Dervish says, a job that “was perfect since I was both a basketball player and a referee and had relevant education but at the same time it wasn’t for me at all.” He quit after just two months and became a dance teacher in various private dance schools in the north.

“On top of it, I was also doing some voluntary work in the community. Every Saturday I would go to various villages and run dance workshops for local kids there. I would visit seven-eight villages daily. People loved it. It was organised by the Youth Department and the requests for these clasess were just flowing in.”

Then, in 2010, Dervish arrived at the point where the gestating idea of his own fusion finally came clearly into focus and took shape. “That was the year my whole life changed,” he recalls. “I decided to start my ‘fusion project’. I found myself.”

Dervish knew that he wanted to work with children and to help change their lives through art: “Dance has no borders, I thought. I will use arts as a tool to reach people and change them. Especially kids to give them freedom of thought and colour. And to let them know that sharing is caring.”

Dervish had some money saved so he rented a shop in one of Nicosia’s suburbs. Then he met Bekir, Hasan, Harun and Taner. The youngest was 13, the eldest – 16. They were dancing in the streets. “They knew what they wanted and they were in love with hiphop culture but at the same time they were lost. They felt different from their families and neighbours but how could they get away from there? So I told them that I had this dream to start a dance group and that we were going to do it together and at first they just were laughing at me. They didn’t believe me.”

But Dervish perservered. “We started using the place I rented. The first month just these four guys and I. The next month there were 30 kids. I called the group New Generation.”

After a while Dervish ran out of money and he had to let the shop go. For a year the group trained in a borrowed set up while he continued his search for the ideal space.

“The kids were growing more confident. Their dancing skills were improving. All we needed was a place where we would feel we belong. That’s when we found the shop in Uray street in the old town. To this day, I’m sure it wasn’t a concidence.”

This is how Studio 21 was born.

“Of course, I could have found somewhere else but this place is very special,” says Dervish.

“If I had cared only about dance it would have been different but it was also about these particular kids and their own community so being so close to it was the best that could have happened.”

A year raced by and when Dervish cast an eye over his group it had grown and changed. Now he had not only kids from the north but also kids from the south had joined in.

“We had so many different nationalities,” he says, smiling. “It was like a dream. We had Turkish Cypriots, Turks, Bulgarian Turks, Russians, Filipinos, and all because I was doing something that nobody else was doing.”

And just what was that? “I was sharing with them. We didn’t have money but I was giving them my time and I suppose being like an elder brother. I was also learning from them a lot. And with the dance group, I was teaching them how to get to know their bodies. This is crucial. This is all I understood from all my life as a dancer, doing these different styles. If you are aware of your body, you are a performer, a dancer, you can move. I was also teaching them about acting because in every single dance you get into a different mood.”

He did have some run ins with parents though. “It was painful to see how closed-minded we can be. Cypriots think they are a superior and good and all the problems in this country are created by ‘others’. Cypriots on both sides are like this. They don’t want to see the truth — that the problems we have we created ourselves.”

He also ventured south starting a series of classes outside Phaneromeni school with its large intake of migrant children. “It worked amazingly there as well. In a way it was the same thing as in the north. Same kind of children from different countries…”

Over the next few years the idea began to take hold that a community celebration of sorts would be a good way of marking progress and so the first Yuka Blend festival was born. “It was August and we felt we were ready so I said ‘let’s organise a party’. Two weeks later we had our first Yuka Blend. It was a real revolution. After this every year it got better.

“In 2016, we were very grassroot and anarchic. We didn’t get any permissions. We did it all on our own within the community and the community didn’t object because we had gained their trust. They knew we were doing it for them and their kids.

“By 2018, everybody was working with us. Our budget was huge, we had sponsors from everywhere, people wanted to be part of it.

“We had 30,000 visitors, 10 stages, many international and local artists, both from the north and south, djs, volunteers, all the kids were involved, you name it….”

The festival was an established success. Pleased and proud as he was, Dervish somehow knew that it was time to take a step back. “When you grow bigger, everything changes. It is a risk you are taking. I could see we were losing some perspective because after all is said and done we came from the grassroots of the community. So we had to grow smaller again, as it were, and reach out to other places, get different people involved.

“I believe that in our life we want more and more and by the time we get it all we lose all our feelings,” he says, explaining his decision to downsize.

“I am an artist. I live with feelings. I believe in going slow, in having positive energy. I don’t need millions. I am not in a hurry. I am not going to stop. It is kind of over but not really. We are evolving.

“In 2021 we are going to do some small but effective things. I want to organise a small Yuka Blend in the south. It is my dream. And I also want to move the Good to Remember project to the south. I want to cover the whole Nicosia and not only part of it.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences