After four years in Limassol, the bass player and manager of one of Europe’s three largest rock bands remains resourceful and relentless. THEO PANAYIDES meets a man who has achieved staggering success singing about something that matters

Par Sundstrom has done this before. A Google search on the bass player of Swedish heavy-metal band Sabaton takes me to an interview he did during the press tour for Sabaton’s album The Great War in 2019, during which he informs the journalist that their interview is one of about 400 interviews scheduled for that tour. “For [previous album] The Last Stand I did 350 interviews for Europe, but spread out throughout 12 months. Now it’ll be 400 in one month,” he mused at the time. Our own conversation may be slightly unusual in that it takes place in Limassol, where he’s lived for the past four years; still, it’s fair to say my questions hold no secrets for him.

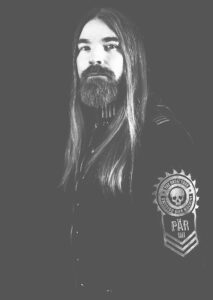

Well, yes and no. His lifestyle is certainly demanding (Limassol is just a base; he’s on the road with Sabaton about 250-300 days a year), then again youth is no longer a prerequisite for this sort of thing; the older generation of rockers – Scorpions, Kiss, the Rolling Stones – are still touring in their 70s. More importantly, Par’s own personality is a long way from raw youthful energy, indeed his skill set probably works better in a middle-aged man. He does look like he plays heavy metal, with his long hair and fierce-Viking beard, but it’s a uniform more than anything. You’re not really a rock musician at all, I venture cautiously; you’re more like the CEO of a multi-million-euro business.

He pauses, looking slightly abashed. “Yes,” he replies at last. “I am a CEO, yes. And it has become quite a big business.”

We sit at a bar called Bono, chosen not because it’s named after a fellow rock star (if indeed the U2 frontman had anything to do with it) but because it’s close to Sabaton headquarters, a cluttered office filled with merch and memorabilia. There are gold discs, pyramidal concert speakers, stacks of Sabaton T-shirts (the band’s e-shop is based here; there’s a warehouse where the stuff is actually stored); Sabaton jigsaw puzzles are apparently coming soon. A pair of counters read 453,944 and 996,565 – Instagram and Facebook followers, respectively – though in fact the counters are props from a music video and already outdated. The numbers are jaw-dropping in general: the band’s YouTube channel has 1.22 million subscribers, a smaller channel called Sabaton History has nearly 300,000. Many of their videos have been viewed over 20 million times.

Sabaton on stage

But the numbers tell only half the story. “The traditional way of being an artist,” explains Par, sipping a juice at a high-stooled table, “is that the first thing you do – because you are lazy, and you just want to focus on your music – is you get a manager.” Sabaton never went down that route; instead, Par himself is their manager (there are also 25 full-time employees, including seven in Cyprus). The result is that the band – very unusually, in the music world – control everything: the rights to their songs, the merchandise, the concert tours. This was always the idea, right from the beginning, back in 1999 when 18-year-old Par and lifelong friend Joakim Broden (the only remaining founder members of Sabaton) divvied up the labour between them: “He was focusing on the music side, and I was taking care of the management side”.

This was always, it appears, his personality: a manager, a fixer, an organiser, a troubleshooter, resourceful and relentless and hard-working. (What’s his lifestyle like in Limassol? “I work,” he replies with a shrug.) Par is indeed Swedish-born (we’ve left out the umlauts in his name and surname, but rest assured they’re there), both he and Joakim hailing from the town of Falun, population 37,291 according to Wikipedia. It sounds like a page from the heavy-metal playbook, rebellious young guys going nuts in a dead-end small town, but rebellion never really entered the picture. “I always felt Falun was a great city to grow up in,” he says mildly. “OK, it’s relatively boring when it comes to concerts and stuff.” Par’s parents supported his musical ambitions, albeit also pushing him to find a regular job; he only quit his day job – as the manager of a cleaning company – in 2006. Sweden is supportive in general, a good place for aspiring rockers. Only Finland has more rock and metal bands per capita.

The Sabaton story is surprisingly wholesome. The band started small, helped out at venues and got gigs in return. They started writing historical songs in the early 00s (Joakim and Par co-write most of the lyrics) because “we wanted to sing about something that mattered”. Today, having made it big, “Sabaton has become more of a historical institution. We do not only write the songs anymore, we also produce documentaries”.

That’s the second YouTube channel, Sabaton History, featuring around 100 videos tying the songs to the historical events that inspired them, from Sparta to the D-Day landings and beyond. Then there’s Sabaton Open-Air, their four-day music festival in Sweden that attracts fans from over 40 countries – and many fans are also young parents (the average Sabaton fan is around 30 years old), which is why the fest has a special kids’ area where children can be left in the care of trained professionals while their parents hit the mosh pit, “and they will be taught to play guitars, they can play games, they get free food and everything”. Par frowns, with the air of a hotel manager adding a warning about making noise late at night. “You cannot return drunk,” he cautions. “Then we will be very angry and upset.”

Not very rock’n roll, surely?

“I think that the days of rock’n roll lifestyle are over,” he replies thoughtfully. Times have changed in general: “Nobody’s impressed if someone throws a TV from a hotel anymore, or takes a motorbike and crashes into a wall or something. People just say ‘What a stupid idiot’. While people in the 80s thought ‘Oh wow, that’s awesome’… I think a lot of things have changed in our industry – mostly for the good, for me. I prefer this.” Being a rock star used to be about trashing hotel rooms and ingesting copious quantities of drugs, now it’s more about curating your Instagram and releasing your own line of hoodies.

His surprising (but surprisingly plausible) theory is that boredom – a vanishing commodity these days – also has something to do with it. When you’re in a band you’re always waiting around – whether it’s for transport, or a sound check, or an interview, or a signing session – so musicians would often get bored and decide to drink or party. Today, however, “everyone’s got a phone” and can pass the time more constructively. One wonders how different the history of Led Zeppelin might’ve been if they’d skipped all that heroin and Quaaludes and just spent the time playing Candy Crush.

Boredom is a foreign country to Par Sundstrom. “I wake up in the morning and I’m super excited,” he tells me. “I look forward to going to the office.” His drive and enthusiasm have been central to the band’s own history – including the ‘crossroads moment’ in late 2011 when Sabaton essentially broke up, leaving only Par and Joakim from the original lineup. A year earlier they’d signed with Nuclear Blast, the biggest metal label in the world; some (like Par) felt the band could be huge if they went all-in, others weren’t ready to make that sacrifice. That’s the trouble with being in a rock band: you join at 18, for a laugh more than anything, then suddenly you’re 30 and “you have some wife or girlfriend saying ‘Hey, I want some little kids running around here’ – and they also say ‘You need to start paying the bills as well’, and ‘I need to have you at home, because I can’t take care of all this myself’… That’s when you have to make a decision. And some people didn’t sign up for that.”

He himself was fully signed up, always had been: “I never had any backup plan”. This, again, seems to be his personality: driven, competitive, forever organising and pushing and learning. You learn how to play the bass guitar, he recalls, “then you realise someone needs to make a phone call to book a show,” so you learn that as well. “Eventually you need to know how to drive the tour bus, or how to fix the tour bus when it breaks down. You need to learn different things along the way – and I was always the one who liked to learn new stuff”. He’s designed posters, edited videos, organised catering for festivals; he did the pyrotechnics for Sabaton concerts. Some young men become rock stars as an act of rebellion, two fingers up at the world; Par doesn’t seem to have an angry bone in his body. Some crave the glamour, but that doesn’t seem to be his motivation either (unless a home in Limassol counts as super-glamorous). He just really likes to do stuff – and, to quote his memory of himself as a kid, “no matter what I did, I wanted to do it more than everybody else”.

Was he also a bad loser? “Yeah, I’m a bad loser,” he replies candidly. “I would say that, sure. You have to be a bad loser if you want to be a winner.” Later, I ask which concert means the most to him, out of all the hundreds he’s done – and he cites Sabaton headlining the Swedish Rock Festival in 2015. Why? Because 16 years earlier, in 1999 when the band had just formed, “I was there with our first demo, in the first year of that festival. I met one of the organisers, I gave him the CD and I said ‘One day we’re headlining that stage. So remember our name’. And he said ‘That will never happen’.” Par smiles slyly: “In 2015, he came and said ‘Congratulations. You were right all along’…”

No surprise, perhaps, that a competitive person also writes songs about war – though he makes it clear that the band don’t celebrate war. “You could see us as storytellers,” he says, their aim being to highlight historical events (mostly battles) without passing judgment: “It’s important to remember that all conflicts have at least two sides. And both sides are right – from their own perspective”. That said, the songs are stirring and emotional, emphasising courage and sacrifice. “Then the winged hussars arrived / Coming down the mountainside,” goes the chant in ‘Winged Hussars’, celebrating a 17th century Polish cavalry unit. “Fight hard! Resist and do what’s right!” goes ‘Resist and Bite’, about the Battle of Belgium. This is obvious fodder for red-blooded young men feeling the pull of testosterone – yet in fact the fanbase is mixed, with a surprising number of women in the audience at concerts.

Ah yes, concerts. They too, it seems, are a kind of war – or a kind of project, like amassing 1.22 million YouTube subscribers – something you have to do unflinchingly, relentlessly. Sabaton have never cancelled a concert; it’s just too complicated to cancel. Par has performed with a fever, with broken limbs; he’s performed with food poisoning, literally using “buckets on the side of the stage” to throw up between songs. They were on a European tour in February 2020, playing for 10,000 people every night in sweaty concert halls – and of course they got Covid (before the world really knew what Covid was), “we had to send home some of the crew members because of flu symptoms that could not be cured”. You just keep going, he explains, powered by adrenaline – “Actually, the body is amazing” – then collapsing at the end of the final encore.

Par keeps going too, even as youth gently shifts into middle age. Limassol helps, in its way. He doesn’t go to the beach much – but he loves the sunshine, and the fact that it’s open late (so he can still unwind when he leaves the office): “I do feel less stressed here, because of that”. Age will presumably slow him down eventually; not even rock stars are immortal, especially when the job is so gruelling. Right now, however, “I feel good the way I am,” he says contentedly, sitting at the table at Bono, “and I think I’m excited for many more years to come”. Happy 40th, Mr. Sundstrom.

Click here to change your cookie preferences