Executed by the Ottomans during the Greek war of independence 200 years ago, Archbishop Kyprianos has always been a poignant symbol, but what that is has fluctuated with the times

Next Friday marks 200 years since a famously dark day in our history.

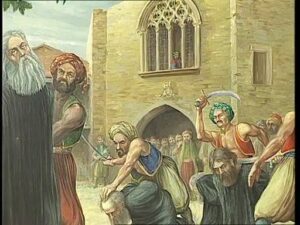

On July 9, 1821, a few months after the war of independence had erupted in Greece, 486 prominent Cypriots were executed by the Ottoman rulers on the island – chief among them Archbishop Kyprianos, publicly hanged from a tree, along with the bishops of Paphos, Kition and Kyrenia, all of whom were beheaded.

For days, the island was plunged into chaos. Four thousand Ottoman troops had arrived from Palestine in May and they now went on the rampage, pillaging churches and terrorising the population. The few schools closed, and didn’t reopen. Most big merchants who’d survived execution fled in haste, and their property was confiscated.

To quote from a recent book, The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary (edited by Paschalis Kitromilides and Constantinos Tsoukalas): “For the rest of the 1820s Cyprus remained inert, under the terrifying shadow of the hecatomb of July 9.”

As the years passed, Kyprianos became something of a symbol – especially after the publication in 1911 of ‘The Ninth of July 1821 in Nicosia Cyprus’, a narrative poem in Cypriot dialect by Vasilis Michaelides which did more than anything to burnish the legend.

“Rather than the blood of many/Better the blood of the prelate,” says Kyprianos in the poem, when a Turkish Cypriot named Kioroglou offers to help him escape – sacrificing himself for the good of his flock, as a true martyr should.

For generations afterwards, throughout the years of British rule, “I don’t believe there was a Cypriot alive – even if they were illiterate – who couldn’t recite parts of the poem, or even the whole poem by heart,” Petros Papapolyviou, associate professor at the University of Cyprus, told the Cyprus Mail.

But who was the archbishop really? And what was his role in the Greek revolution?

Kyprianos, born in 1756, was “a very wide-ranging intellect, for his time”, says Papapolyviou, while Kitromilides calls him “a prominent representative of the religious Enlightenment”. He’d lived abroad for many years, in Wallachia, and was cultured and sophisticated.

From 1810, when he became archbishop, he established two progressive high schools, one of which became the Pancyprian Gymnasium – aiming to produce graduates who were not just pious but also “friendly to commerce” – and dispatched many promising youths (not just clergymen) to university in Smyrna or to study Byzantine music in Istanbul, hoping to educate what was still a very backward island. He was active against Freemasonry, and equally active in fighting the locust plagues that afflicted Cyprus on a regular basis. In many ways, his martyrdom isn’t even the most interesting thing about him.

When it comes to 1821, notes Papapolyviou, the big question is: “Could Kyprianos, and Cyprus generally, have taken a more active role? Did he know about the plans [for revolution]?”

It’s clear from the general plans drawn up in 1820 by Filiki Eteria, the secret society behind the Greek war of independence, that Cyprus had a role to play. It could hardly have been otherwise, given the remarkable influence wielded by the Orthodox Church here. To quote British historian Sir Harry Luke, from Cyprus Under the Turks 1571-1878:

“By an astonishing reversal of fortune, the Archbishop of Cyprus – whose office had been created by the Turks after lying dormant for 300 years – secured in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries supreme power and authority over the island, and at one period wielded influence greater than that of the Turkish Pasha himself.”

Kyprianos was indeed approached by the Greek revolutionaries. This, however, is where accounts start to differ slightly. Kitromilides, in his book, writes that the archbishop was asked to join the society but declined the request, pledging only financial support. Papapolyviou, however, believes there was never any question of Cyprus joining the actual revolution – due to geography more than anything – and financial support was all that was ever requested, though of course individual Cypriots did cross the Aegean and join the fight.

He even mentions the existence of another theory (though he disagrees), according to which the executions of July 9 weren’t even directly linked to the revolution. Rather, the killing of Kyprianos was “a bid by the Ottomans to curtail his political power” and replace him with a biddable successor – though that wouldn’t explain why so many others were killed along with him, both lay and clergy.

The pretext for the killings, in any case, was the arrival in Larnaca in April 1821 of Archimandrite Theophilos Theseus, a fiery clergyman (and relative of the archbishop) who later fought in the war of independence.

Theophilos distributed pamphlets calling on the populace to revolt, an action that enraged Kucuk Mehmet, the Ottoman governor – described by contemporary observers like English visitor John Carne as brutish and “lacking the good manners one usually finds in high-ranking Ottoman officials” – prompting him to draw up the list of 486 names.

Kyprianos, in other words, did nothing directly to provoke his sad fate – and, in the two months that remained of his life, did nothing to try and avoid it. Kioroglou in Michaelides’ poem may be apocryphal, but there’s certainly evidence that the archbishop could’ve escaped execution by renouncing his faith, or fleeing the island altogether.

He refused, his main contribution being a final encyclical on May 16 counselling calm and faith in God, and urging his flock to avoid causing trouble. His stoicism impressed Carne, who praised him as “highly eminent for his learning and piety, as well as for his unshaken fortitude”. One thinks vaguely of Sir Thomas More, another intellectual calmly contemplating the end of his life at the hands of unjust authority.

Kyprianos has always been a symbol, but what he symbolises tends to fluctuate with the times. “For years,” says Papapolyviou, “the dominant idea was, I would say, the sacrifice, the blood offering. The passive attitude of Cypriots”.

Later, from about 1930 when his mausoleum was built in Phaneromeni church – hitting a peak in the years of Eoka – the emphasis changed from being victims to “the Cypriots who fought”, making the archbishop a hero of the revolution.

Now, finally, with 200 years behind us (and calls for his canonisation gathering pace), it’s possible to focus less on the legend, more on Kyprianos the actual historical figure. A many-sided man of rare ability who surely never wanted, or expected, to become a martyr – but, when that became his fate, accepted it gracefully. Sounds good enough.

Click here to change your cookie preferences