The ancient art of falconry has a part to play in modern conservation

By Constantinos Antoniou

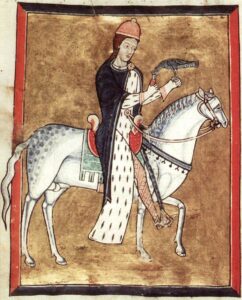

Who can imagine our island as a Mediterranean wildlife oasis where nobles, knights and kings roamed on horseback, hunting with trained birds of prey? Yet this was the reality throughout our island’s history with evidence emerging as early as 11th century BC.

Falconry by definition is the “hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey”. This noble art which takes years of experience to perfect, or as declared by Unesco “a living human heritage”, was a common practice among Cypriots, rulers and kings that lived here from the earliest records until today.

In the Middle Ages, the practice was considered a noble sport, it was the epitome of hunting methods and the ultimate way to capture prey. It was a status symbol and a way of life for the people that reportedly had large number of hunting dogs, and hunting birds which they used to hunt around the island. Roaming on horseback followed by their servants they hunted all around the island especially in the Mesaoria plain and the foothills of Troodos and Paphos forest. Strict laws and regulations and laws protected falconers and their birds such as the laws mentioned by the renowned John de Ibelin. This suggest that the birds of prey, dogs and horses at the time were held in high esteem and were fiercely protected.

Such was the passion for falconry that the Latin archbishop of Nicosia, Ranulf, at a conference held around 1283 complained that the monks “shouldn’t continue to leave their monasteries to go hunting neither possess hunting dogs and hunting birds for this purpose”. Similarly, Czech manuscripts of Ludolf Von Suchen in 1350 describe: “I met a noble man with more than 500 hunting dogs and for every two of them he had a servant to take care of them, also every noble man had 10-12 birds of prey for which they spend a lot of money to maintain”.

The Italian explorer Nicola De Martoni described how when he visited Cyprus at the end of the 14th century, King Jacob I (1382-1398) had in his possession 24 leopards and 300 birds of prey of all species, some of which he used to hunt every day with. The leopards referred to are more likely to be cheetahs as they were widely used at the time through Asia/India and later Italy and continental Europe to hunt down even hooved ungulates such as blackbuck in India and roe deer in Europe accordingly.

Other accounts relate how when the king and his falconers and friends went hunting, he let the birds of prey fly towards wild prey, and the hill was an ideal place and according to evidence the area today’s presidential estate. Leontios Machairas also describes how King Henry II had a falcon breeding centre in Strovolos, where he spent his free time there training them and even died there in August 1324.

The book Chorograffia highlights the value of birds of prey at the time. “Every knight had his own birds of prey, which he could exchange even for slaves,” goes one sentence. So valuable were they that in the National Record in Venice in the chapters of “Consiglio dei Dieci”, the rulers of Cyprus under Venice back then had to auction the bird of prey trapping spots in Cyprus and give them to the highest bidder. The highest bidder would be the one that could provide Venice with the most birds of prey or the first that would trap 30 “good” female saker falcons and 10 “wandering” falcons (referring to migratory female peregrine falcons) and send them there with a trustworthy person to take care of them.

Explorer Villamont who visited Cyprus in 1589 describes how in August the villagers around “Akrotiri ton gaton” trapped a number of birds, under the threat of a death sentence they were obligated to deliver them to the local “Pasas”, where he used to pay them and exempt them from taxes. Fynes Moryson in 1596 describes that the governors of the island had orders to send all the trapped falcons to Constantinople.

Pictures and depictions of birds of prey being portrayed as important symbols and items of admiration exist in Cyprus dating as back as 11th century BC, a golden statue of a pair of falcons found in Curium and exhibited in Nicosia Cyprus Museum. There are plentiful other artefacts, among them the mosaics in the House of Dionysos in Kato Paphos from the 3rd century AD, indicating that both Romans and Byzantines had great interest in falconry.

All the above evidence suggests falconry is an integral part of Cyprus’ culture and inevitably Cyprus’ intangible cultural heritage to its people. Although evidence shrinks in modern times, falconry never ceased to exist on the island, even today.

Falconry worldwide is on the rise, with the art gaining popularity and countries created their own national falconry trust. With the guidance of IAF (International Association of falconry and conservation of birds of prey) with its 110 associations from 87 countries worldwide totalling 75,000 members, younger generations are being educated about the sport.

Falconry’s contribution to the natural world

Although in the previous times falconry seemed to be only taking from nature, in modern times it protects birds and even gives back, through captive breeding and education. In modern falconry only captive bred birds of prey are used, wild birds of prey are off limits for falconers in Europe where falconry is regulated. The captive bred populations serve as a plan B for boosting wild populations when needed, such as the mid-60s disaster with DDT pesticide. When the numbers of peregrine falcons collapsed in Europe, an organisation (The Peregrine Fund) was founded by falconers and captive bred birds of prey were propagated and released to reoccupy the areas where the populations had been decimated.

Such breeding programmes to boost wild populations are still taking place today with captive bred peregrine falcons being introduced in the Polish peregrine tree nesting programmes. Likewise in Spain for the propagation and reintroduction of bonelli’s eagles and in Mauritius for the Mauritius kestrel etc. The falconry trade created the demand and provided the drive and knowledge for the conservation efforts to take place.

Can falconry contribute to our society? Interraction with birds of prey is evidently educating people, allowing them to better understand raptors. This in the long run reduces the chances of people persecuting birds of prey since we are the major cause of their decline, either through direct persecution or destruction of their habitat. Exposure to trained birds of prey enables people to appreciate their majestic nature and importance.

Is there a niche for falconry in Cyprus today? Yes! Considering falconry is legal in almost all member states of the EU and in most of the world, throughout Asia and the Americas, there must be some substance to it.

Falconry is not only a form of selective and closely managed hunting practice. It’s a form of education, conservation and awareness raising. When the right legal framework is created, and clubs and government work together closely, any individual with the passion for the art should be able to pursue it under the proper guidance. Falconry can have a major role in ecologically protecting landfills, crops, vineyards, airports and managing of ‘pest’ species, like crows or magpies, in sensitive areas where guns are not allowed such as suburban environments or places under military/UN control.

Constantinos Antoniou is a wildlife vet and falconer

Click here to change your cookie preferences