They may be more commonly associated with Asia, but martial arts in Cyprus date back to the Bronze Age Alix Norman discovers

Martial arts didn’t originate in China. Or Japan. In fact, the first formalised disciplines (the 18 Buddhist Fists, which became the Five Animal Styles of Shaolin) are thought to have appeared in India, around 500 AD. But martial arts as self-defence have been popular for time out of mind – from the days of cavemen, who needed to protect their land and valuables. And every culture across the world had its own forms. Even Cyprus…

According to Demetris Pavlides, who has extensively studied the concepts involved in martial arts, Cyprus once enjoyed its own, unique forms of martial arts. Though not exactly the Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon stuff of the Orient, they were certainly studied and practised across the island, starting with the gymnasia (or athletic competitions) of the Bronze Age, through to the Pankration of the early Olympic Games (combining wrestling, boxing, and kicking techniques), and the Klotsata of the late Middle Ages (described as a competitive ‘kicking’ event, much like taekwondo).

“Cyprus martial arts enjoy a history that dates back over 10 000 years,” explains the expert, who thoroughly researched the subject both as part of his Master’s thesis and for his newly-released book ‘Martial Arts of Cyprus’. “As far back as the Stone Age, there is evidence of the very beginnings of formalised disciplines – disciplines that later became widely taught and practised as part of the island’s educational system.

“Initially, they were developed as part of military training,” he explains, “and practised mainly by men who were soldiers and farmers. But in later years, they were openly taught, with gymnasia cropping up across the region.

“If you think about it,” he acknowledges, “Cyprus is a country that’s gone through so many wars and conflicts – it would have been impossible for the people not to have developed some form of martial skill. Greek culture was a heavy influence in this respect,” he adds, “and the training and development of martial arts in both cultures are very similar. But what sets our indigenous arts apart is the improvisation – there were no set, specified techniques in Cypriot martial arts; rather, fighters would improvise their moves based on prior knowledge – and the music.

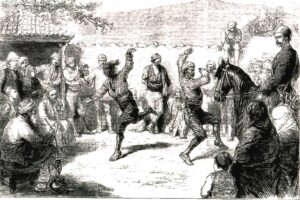

“The original Cypriot martial arts often took place to the accompaniment of live music,” Demetris explains. “It’s primary purpose was to give a rhythmic momentum to the fights – similar to primitive African cultures whose fights were always executed to music in order to synchronise certain movements. So when foreign rule forced our local wrestling matches and combat training to go underground, it was natural that martial elements and skills would resurface in dance.”

Capoeira (a martial art developed by African slaves in Brazil during the Portuguese colonial period) is similar in this respect, Demetris reveals. “Our local martial techniques – like many similar disciplines that went underground thanks to foreign rule – show up in what, today, we would consider our traditional folk dances! So in Cyprus, “he suggests, “we get the Knife Dance, the Sickle Dance, and Antikristos – all of which derive from martial knowledge.

“If you look closely,” he explains, “you’ll find that Cypriot folk dances were relatively unstructured before the mid-19th century. Like our indigenous martial arts, steps, techniques, or movements were often improvised, and it’s speculated that Cypriots incorporated their previous knowledge of martial arts into their dances. Especially when foreign occupation attempted to stamp out formal training.”

Kasapiko, or The Knife Dance, Demetris postulates, closely resembles the ancient Greek ‘Pyrrhic Dance’, which was a means of martial training. “This dance was performed by armed men who moved to warlike rhythms, their movements echoing the techniques used in battle.”

Then there was Choros tou Drepaniou, the Sickle Dance – most probably created to present the participants’ proficiency with a deadly implement – in which dancers simulate various combative techniques: the rotation of the sickle around the dancer’s neck, shoulders, waist, and legs.”

Antikristos, he adds, is another notable example. Performed in pairs, the dancers mirror each other’s movements, leaping, turning, sitting, slapping their boots, clapping their hands across their bodies, and hitting the ground with their palms all in an effort to highlight their physical skill. “It’s a dance that strongly echoes the techniques once used in ‘Patsos Klostos’,” says Demetris.

“These dances reflected martial skills that could no longer be openly practised,” he discloses. “At the start of British occupation, for example, wrestling matches and competitions were commonplace. But given the powerful element of patriotism and the implied desire for union with Greece – the country where these wrestling techniques originated – such activities were considered too political in nature; a possible symbol of revolt.

“So wrestling and similar sports were quickly stopped,” he adds. “And both the Cypriot national games and Cypriot martial arts gradually slipped from view. And yet,” he notes, “their elements remained: hidden in plain sight, in the folk dances of yore…”

With Martial Arts of Cyprus, Demetris hopes to revive many of the ancient practices. An expert in the study of martial arts, as well as a life coach and founding member of the European Mentoring and Coaching Council, he believes martial arts offer a means to cultivate both body and soul, encouraging self-development and humanity. And though he admits there’s a great deal of research into our ancient practices and techniques still to be completed, the fact remains that Cyprus martial arts did once exist. And could, in time, be brought to light again.

The book Martial Arts of Cyprus is available from Soloneion in Nicosia, Academic Bookshop in Larnaca, and from Kyriacou Bookshops in Limassol in both Greek and English editions at a cost of €15

For more information, visit the Facebook page ‘Martial Arts of Cyprus’

Click here to change your cookie preferences