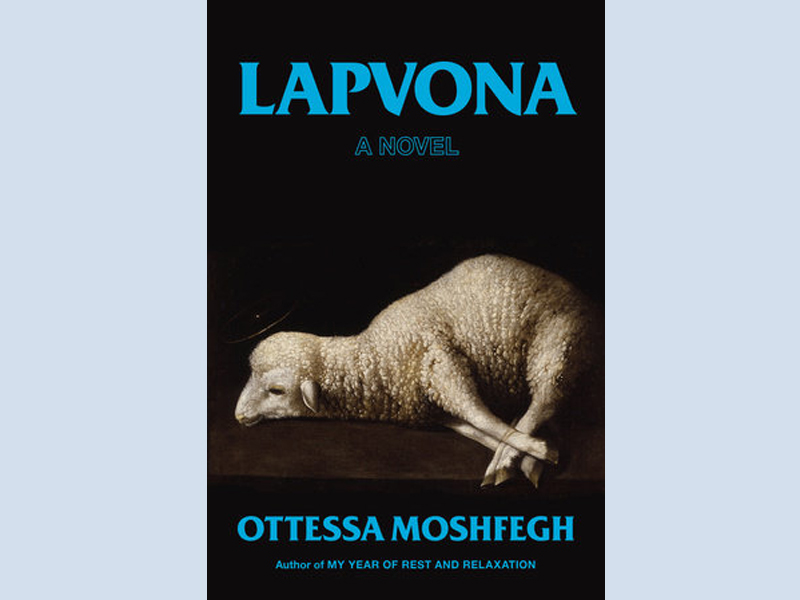

At the end of the penultimate chapter of Ottessa Moshfegh’s latest novel the narrator suddenly breaks the omniscient, third-person voice that has told the story so far. Addressing the reader in the second person, the narrator challenges us to ‘find some reason here’. It saddens me to say that I let the narrator down.

Throughout the book, which tells the story of a famine year in the imaginary mediaeval town of Lapvona, I kept trying to find some reason for anything that happened. I kept trying to discern the point of the incessant depictions of a mediaeval world in which everyone is constantly either being grotesquely abused or grotesquely abusing others.

I got that some of them were played for, albeit dark, laughs. For example, the most successfully drawn character is Ina, a woman of indeterminately ancient age who, despite never having been a mother, was miraculously provided with breastmilk in such perpetual abundance that she was able to act as wet nurse to multiple generations of Lapvonians. Comically – though never explicably – the attachment of the village’s menfolk to Ina’s nipples lasts well beyond infancy, and there is a steady stream of men who seek comfort by visiting Ina’s hovel to suck on her now milkless breasts in exchange for basic gifts.

It should also be noted that after the famine, when all the residents are made infertile due to malnutrition, Ina stimulates the fecundity and lust of Lapvona by applying a magical ointment made of her own, cooked-down urine and masturbating most of the men who used to feed at her bosom as babies. Is Moshfegh making a statement about what it takes for a woman to thrive in a system set up to disempower her? Maybe, but I really wouldn’t count on it.

There is a plot of sorts that centres on Marek. The child was conceived incestuously – of course – before Marek’s mother, Agata, fled from her rapist brother. Agata doesn’t have much luck, as Marek is ultimately born while she is being used as the child sex-slave of Jude, a shepherd who raises Marek as his own after Agata runs away. Needless to say, Jude is brutally violent towards his adopted child. Marek, meanwhile, is addicted to childhood and possesses an obsessive fixation with his own piety. This doesn’t stop him murdering his best friend on a whim, however.

Perhaps logically for a world in which nothing makes much sense, this murder acts as the beginning of Marek’s eventual ascension to the lordship of Lapvona. The book ends with an act of such vileness that it leaves the reader in no doubt as to just how unfit for this role Marek really is.

Why? I just don’t know.

Click here to change your cookie preferences