Cyprus is condemned by history and geopolitics to be a hub of one kind or another. It is a tightrope role that Cypriots negotiate pragmatically and with gusto. Nice to the Anglo-Americans, friendly and amorous to the Russians and obedient to the Europeans. It doesn’t always work, but it comes naturally when you are a small fish in a big pond.

Last week the Republic of Cyprus (RoC) was reprimanded – bullied if truth be told – by the US and Britain for allegedly tolerating breaches of sanctions against Russia but as British citizens and others fled Sudan and Britain used Cyprus as a transit haven, the island’s reputation was restored overnight from a sanctions-busting hub to a refugee evacuation hub.

The RoC implemented a sanctions law as required by the EU but with a light Levantine touch. It is not bound to enforce additional sanctions imposed by the US and Britain although it is wise not to risk secondary sanctions and tweak its sanctions regime accordingly.

The US is a powerful country, and the best policy is not just to be nice but also not too contrary with American leaders. Britain is also a powerful country and the best way with the British is to be polite and agree to fudge disagreements into vague compromises.

Fudge is also the EU way. The EU regulation on Russian sanctions is a fudge masquerading as coercive when it really isn’t. It defines what, how and who is sanctioned but leaves implementation and enforcement to individual member states – as indeed it must. The EU has to rely on the machinery of enforcement of member states because it has no federal agents of its own to enforce compliance like the Feds do in America.

EU sanctions law requires member states to ensure there are penalties for breaches of the sanctions regulation in place and that they are effective, proportionate and dissuasive though always within the four corners of EU human rights law.

The European Commission must be kept informed of implementation measures on pain of enforcement proceedings if states systematically fail to comply. Enforcement proceedings are rare, and non-compliant states are usually forced to toe the line politically rather than by legal enforcement.

As far as the 2014 EU sanctions regulation is concerned, member states have a flexible margin of appreciation that takes into account national idiosyncrasies. A quick comparison of the penal laws passed by member states as at 2021 for breaches of sanctions law shows wide differences between them.

Many introduced criminal sanctions with substantial fines and maximum terms of imprisonment of up to five years; the Baltic states have higher maximum terms and fines but others – notably Italy and Malta – have only a system of administrative fines in place.

Cyprus has both administrative fines and criminal offences punishable with imprisonment of up to two years. It is a light touch but unsurprising given Cyprus’ close association with Russia and the large number of Russians and Ukrainians that have settled in Cyprus.

One interesting aspect of the EU regulation is that it is expressly made subject to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU that protects the right to use and dispose of one’s property without having it frozen indefinitely without compensation unless it is necessary and proportionate.

The Charter also provides that penal laws cannot punish people for conduct that was not a criminal offence when it took place. Member states must take cognisance of the Charter when implementing EU law, which means that criminal penalties cannot be imposed if their effect is retroactive.

The 2014 regulation and its updated list of sanctioned individuals after February 2022 must be applied in a way that strikes a fair balance between EU public policy and individual rights. The sanctions regime is important after Russia’s full-scale attack on Ukraine in February 2022, but individual rights cannot just be jettisoned as if human rights protection discriminates against rich Russians and their associates – the whole point of human rights protection is that it is universal.

On April 18, 2023, the Guardian Newspaper in England published an article that alleged a Cyprus connection with the Russian billionaire and Chelsea FC benefactor Roman Abramovich, who was sanctioned after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine of 2022 “for his very good relations with Vladimir Putin.”

He was previously lauded and applauded by all for his generosity to Chelsea FC, only to be cast aside as a reject in a classic case of guilt by association with Putin even though this was at a time when it was not a criminal offence to have good relations with the Russian leader.

His inclusion on the list of sanctioned persons was seemingly based on an association at a time when it was not a crime and made a lot of business sense to be on good terms with the most powerful man in Russia. In fact, his association with Putin was part of a claim against him by Boris Berezovsky in 2012 in which he was successfully defended by Jonathan Sumption QC who was immediately afterwards made up to the UK Supreme Court as Lord Sumption.

Similarly, people with a previous association with Abramovich cannot be penalised for acts done before Abramovich was sanctioned – assuming he was lawfully sanctioned.

The focus of the Guardian article “The Cyprus Connection: the family firm that helped pour Abramovich’s millions into Chelsea,” was conduct that was not unlawful when it occurred and as such was mischievous and stale news.

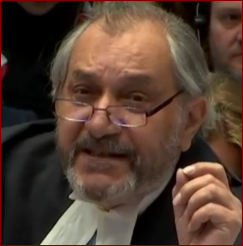

Alper Ali Riza is a king’s counsel in the UK and a retired part-time judge

Click here to change your cookie preferences