President Nikos Christodoulides suffered a few embarrassments in his first hundred days in office, mostly related to some bizarre appointment choices, but these could be put down to inexperience as well as his eagerness to reward individuals that supported and helped him during the election campaign. He also had to offer something to the party chiefs that backed him.

Every president has engaged in the distribution of the spoils of power when he is elected, and it was never going to be any different for Christodoulides despite his election promises about ushering a new era of government, by appointing technocrats, young professionals and people that had never served in government before. He did not keep these promises nor the one about appointing a committee to assess appointment choices. The committee may still be set up eventually, but most appointments have already been made.

Some election promises have been kept, but the main concern was to curry favour with the electorate rather than to set a policy marker. The increase in the Cost of Living Allowance was aimed at keeping happy unions and the public sector employees, who were the main beneficiaries, with no concern shown for the harm it would cause the economy. As for the scrapping of the twice-yearly exams, it was a clear case of pandering to parents and teaching unions, rather than a decision based on any educational criteria.

Christodoulides kept his election promise about seeking a more active involvement of the EU in the Cyprus problem, although it was an empty slogan, which has been exposed as such in the last three months. It was always a non-starter, as the Turkish side would never agree to it even in the highly unlikely event that Brussels obliged. Brussels never had any intention of taking a leading role, while Christoulides’ much-trumpeted visits to Paris and Berlin produced nothing other than expressions of support for talks under the auspices of the UN.

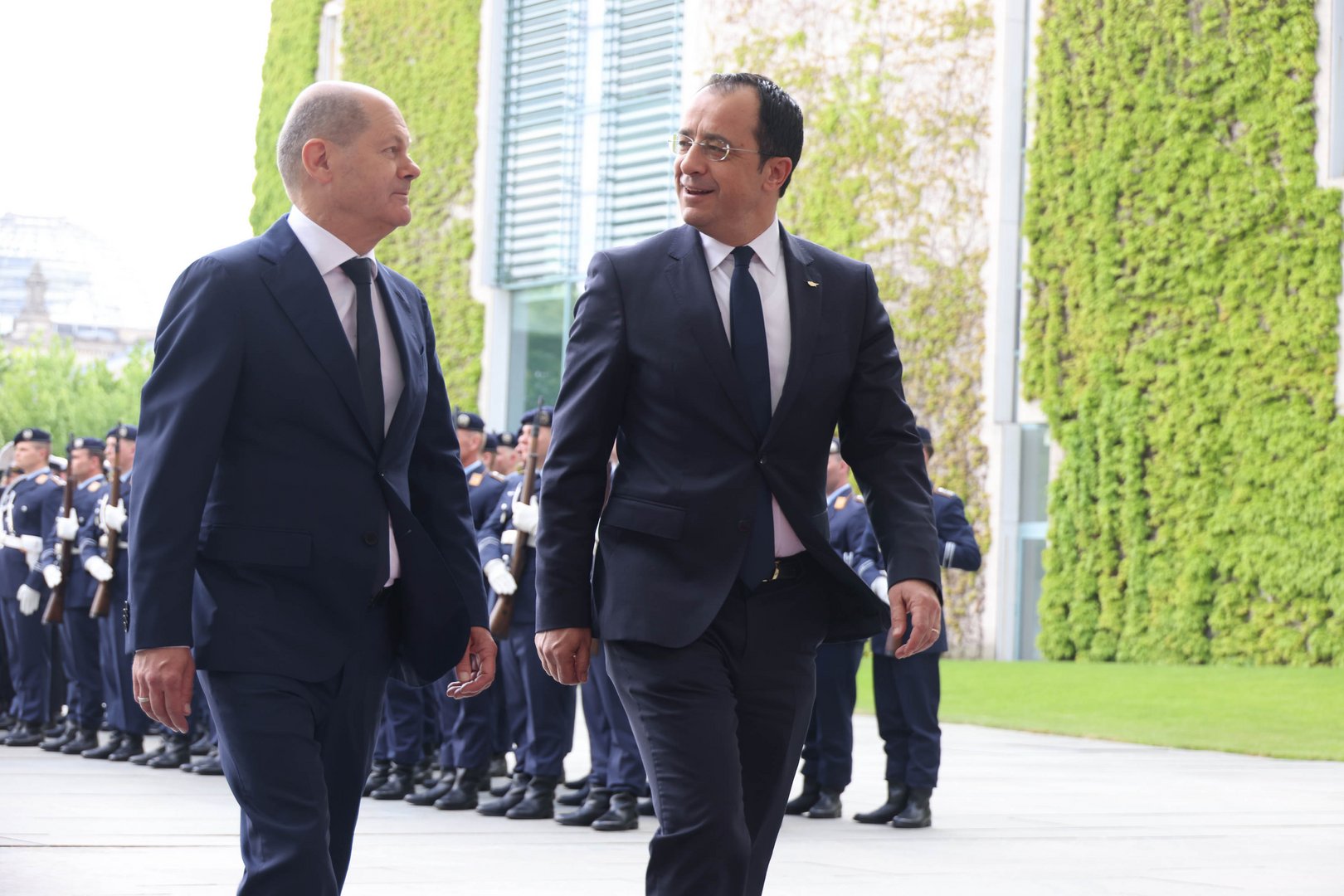

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz took a swipe at both sides for the lack of movement on the Cyprus issue, after his meeting with Christodoulides, saying that for talks to gain momentum it “requires political courage from both sides”. He said he did “not know if there is enough will from both sides.” This probably also reflects the thinking of Brussels about Christodoulides’ idea which he likes to market as a ‘proposal’. If it is a proposal, it is a proposal without substance, guaranteed to be ignored. The danger of resorting to such gimmicks, is that it destroys the president’s credibility abroad.

Realising that the proposal had not been taken seriously, the government changed tack, with spokesman Constantinos Letymbiotis, 10 days ago, coming up with the rather ludicrous warning that Christodoulides’ proposal “will not be on the table forever”. Were we doing the EU a favour in making a vague proposal? This comment raises suspicions that the ‘proposal’ was primarily geared for domestic consumption, the president wanting to be seen to be taking an initiative on the Cyprus issue even though he knew it would lead nowhere.

Given his repeated assertions that the Cyprus problem must be solved, as a matter of priority, Christodoulides had to be seen making some effort. His ‘efforts’ however have been half-hearted and consist of nothing more than making statements about his support for a settlement and his readiness to return to the negotiating table immediately. If he were so keen why has he not appealed to the UN secretary-general, the only person who could arrange the resumption of talks? This has been the message of the EU, but he still refuses to give up on his ‘proposal’. On Thursday evening he told an audience in Limassol there seemed to be prospects of a leading role for the EU, within the framework of the UN. He arrived at this conclusion from a telephone call he had received earlier, he said.

Sharing information about a telephone call he had received seems more a case of political showmanship – an attempt to keep alive his futile effort – than any serious attempt to persuade the Turkish side to return to the negotiating table. In this regard, according to Letymbiotis, the president, with his public statements was “contributing to the cultivation of a positive climate”. Can anyone seriously believe that, at this stage, public statements will achieve anything other than to promote the myth that Christodoulides is interested in a settlement?

The reality is that a president, sincerely committed to a settlement, would not have appointed as his Cyprus problem advisor a retired ambassador, who had spent his entire career at the foreign ministry undermining peace initiatives and ensuring they ended in failure. How believable is Christodoulides’ interest in a settlement when the national security council he has established will be run by Tassos Papadopoulos’ most trusted and loyal associates, a man with impeccable rejectionist credentials?

This adds substance to the view that all the president’s Cyprus problem proposals, initiatives and statements are for appearances’ sake. His objective seems to be not the start of meaningful negotiations for a settlement, but to create the impression that he did everything in his power to secure a resumption of the talks but failed because of the Turkish side. It has been a successful ploy, but only domestically.

Click here to change your cookie preferences