In an open-hearted man whose friendships and feuds are legendary, THEO PANAYIDES finds a famed print maker with works spanning from postage stamps to the Pushkin Museum

It’s a tricky moment for Hambis Tsangaris – also known simply as ‘Hambis o Haraktis’ (Hambis the printmaker), which is how he signs his two-volume autobiography. On the one hand, the many accolades he’s amassed over a long career culminated last month with the Europa Nostra award – Europe’s top heritage prize, not often given to artists – which he won “for his achievements in fostering connections and understanding among communities in Cyprus through his work with heritage”. On the other, his life is heading into uncharted waters with the departure of Hélène Reeb, his second ex-wife and a permanent fixture at the Hambis Museum of Printmaking, one of whose rooms is named after her to honour her contribution. She actually calls halfway through our interview and he talks for a couple of minutes, very quietly and politely, before hanging up. “End of an era,” he sighs. “But she’s a wonderful person.”

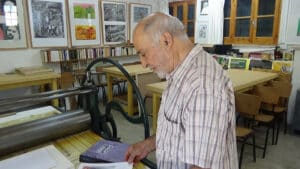

He and Hélène met here, 20 years ago, when she arrived as a tourist – ‘here’ being the tiny village of Platanisteia or possibly Plataniskia (Google Maps has the former, the ‘Welcome’ sign at the entrance to the village includes the latter; the official name is apparently quite fluid), located on the other side of the highway, and a few minutes up a narrow winding road, from Pissouri. 76-year-old Hambis moved here in 1988, looking for a quiet place to work; it’s a former Turkish Cypriot village, meaning he was able to claim a house as a refugee (he was born in Kontea, near Famagusta). He opened the Hambis School of Printmaking in 1995 – meanwhile working as a graphic-arts teacher in Limassol to make ends meet; the ‘school’ is free, students paying just for their materials – and the museum in 2008, all clustered together in a couple of old stone buildings surrounded by trees and vines.

That seems to be his general worldview: open-hearted, friendly to all, but only as long as they’re straight with him. He himself believes in honesty, he affirms: “I’m a straight talker. And I pay for that – I pay dearly, in fact. Many don’t like that I’m so direct with them”. He’s among the most beloved Cypriot artists – but not universally beloved. “Many, many people have helped me. And many, many others have ignored me, or fought me.” His friendships are legion, but his feuds are also legendary.

The friends outnumber the foes, especially these days. He’s grateful to all who helped with Europa Nostra: former European commissioner Androulla Vassiliou who supported him, Nicosia mayor Constantinos Yiorkadjis who put forward his actual candidacy, Christos and Leda Ayiomamitis who sent supporting videos and photos during the “preliminary stage”. Social media was a challenge, due to the sheer outpouring of goodwill after he won. “I don’t want to just post ‘Thank you to everyone’ on Facebook, I never do that”; he prefers to reply individually – but his initial post announcing the prize had 1,100 likes and 750 comments just by itself. “I sat down yesterday, at various points during the day and night, and replied to everyone, one by one.” He sighs, thinking perhaps of his newfound solitude: “What I feel most strongly right now is the love of so many people”.

Hambis in his village museum

Others have been less benevolent. I ask about state support, and he shakes his head: “The state… I say this all the time – and let them come and prove me wrong – the state is absent. Permanently, at least in the past 10 years. For me, the Ministry of Education and Culture doesn’t exist. I don’t just mean ‘It doesn’t do its job properly’, or ‘It doesn’t help’. It doesn’t exist.” He never got a penny to help with creating the museum, he says bitterly, despite repeated requests – at least till Christofias took over, “and then we could breathe”. (Much of this is party politics, of course; Hambis is viewed as Akel, having actually worked for its newspaper Haravgi in the 1970s, though he claims to have left the party years ago.) Then you have the inhabitants of Plataniskia – not all of them, to be sure, but a significant faction, mostly allied to a former mukhtar. The feud between Hambis and his fellow villagers escalated to a point, in 2018, when his access road was deliberately blocked, forcing the school to close down briefly and prompting ex-president Christofias to intervene on his behalf, urging the government to take action.

I briefly wonder how much of this is for public consumption – but in fact it’s all in his autobiography, albeit with some names redacted. (Like he says, he’s a straight talker.) “We were going hither and yon to spread the word about printmaking in Cyprus,” he writes in the second volume, “but back in Plataniskia the war against us was getting worse”. It’s all there, from verbal attacks on visitors – especially the parties of schoolkids who often arrive on day trips – to the Museum’s flower patch being taken over by the mukhtar’s family as a vegetable garden for their own use. Then again, earlier skirmishes in the ‘war’ had a happy ending. “I’m going to bomb your house,” was the welcome he received back in 1988 – but the neighbour who made that threat (he’d been using Hambis’ current home as a barn for his bulls, and didn’t appreciate an outsider barging in) later became a good friend.

Part of the problem is that Plataniskia is an in-between place, a casualty of the invasion. Most of the current villagers are refugees from Eptakomi in the Karpas peninsula, brought over in a kind of exchange with the old Turkish Cypriot inhabitants – most of whom, in a strange irony, were actually relocated to Hambis’ old village of Kontea; it’s a place where no-one really feels they belong. Hambis has some compassion for the villagers (“these wounded souls, who came from Eptakomi with a thousand stories behind them”), just as he himself still pines for Kontea – a village of vines like the ones that adorn his museum, a village where he used to paint endlessly (printmaking came later), having been an artist since childhood.

There was no money, of course. His father did odd manual jobs, from digging holes to lugging crates at the port in Famagusta. His mum, it turns out, was an artist herself – though he never found out till years later, when he happened to discover that the two embroidered canvases in their old home (which he’d assumed were part of her dowry) were in fact her own creation. Hambis is part of the key generation, the one when Cyprus awoke – slowly and awkwardly – from its centuries of rural slumber. His son and grandson are also artistic, and have all the usual opportunities to express their talents. His mother had no such opportunities, and could only embroider in private – but Hambis himself, born in 1947, had a fighting chance, even with no money and no obvious path to becoming an artist.

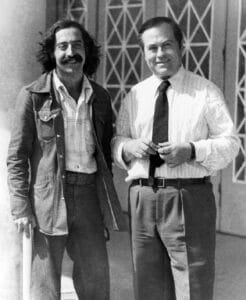

With his mentor a Tassos in 1975

“I have goals,” he explains when I ask about his personality, “and I don’t back down. Whatever it is, I always persist. The biggest example is how I finally got to study: I wanted to study, and I struggled for 10 years. 10 years!” By the time he went to art school in Moscow he was 29, married with two kids. He recalls a fellow student offering him a smoke on the first day, with the words “Cigarette, uncle?”.

He tells the story, though of course he’s told it before; that’s the problem with interviewing someone of Hambis’ stature, he’s told these stories dozens of times. Aged 22, working as a construction worker in Nicosia, he went to Haravgi on the off chance (he knew a journalist slightly) to ask if they knew any better jobs – and got a job there, first as a proofreader, then as their Moscow correspondent. Aged 23, having tentatively moved into printmaking (he’d made four linocuts and five woodcuts), he went to an exhibition by famed Greek engraver A Tassos and showed his work to the artist, who became his mentor. Aged 28, now in Moscow but forbidden to study by the authorities, he made an impression on Akel chief Ezekias Papaioannou whose wife was terminally ill in a Soviet hospital – “He appreciated my attitude. Yes, I was fed up [with life in Moscow] but I supported him, it was a rough time for him” – and suddenly the path was clear. Hambis spent six years at the Sourikov State Institute, graduating with such distinction that 19 of his works were bought by the Soviet art establishment, seven of them ending up at the Pushkin Museum.

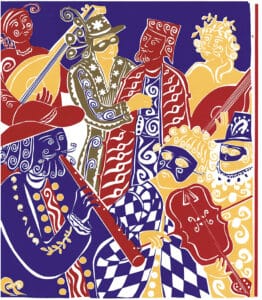

His prints now hang in museums and collections in several countries, from Australia to the UK to the Czech Republic (plus Greece and Cyprus). One of his works, Spanos and the Forty Dragons, has even appeared on postage stamps – and he’s done it all, almost all the different kinds of printmaking: from carving grooves on raw potatoes in primary school to linocut, woodcut, copper engraving, metal engraving, etching, aquatint, drypoint, silk screen, the technique known as ‘sugar lift’. The only one he hasn’t attempted is the digital work that’s all the rage these days – not because he’s old-fashioned, but perhaps because he thrives on manual labour: when not working he’s generally to be found in his garden, “just now for instance I opened the museum but I was also pruning the vines, because their branches were touching the roof tiles. There’s always something.”

He’s alone now, for the first time in years – but perhaps he was always alone, this friendly but stubborn man with the powerful will to create. Yes, it’s also a will to communicate, “fostering connections” as Europa Nostra put it, travelling to villages all over Cyprus to preach the gospel of traditional printmaking (a big reason why he won the prize) – but “I made the books. I illustrated the folk tales, the kallikantzaroi. As far as the artistic side is concerned, I was alone”. Above all, he moved out here, away from the world, building his little empire – there are 5,000 pieces in the small museum, he tells me proudly, everything from old Hogarths and Goyas to many of the world’s top printmakers – in the face of local hostility and official indifference. He did it all himself because he had to, from Kontea to Moscow and beyond.

A certain melancholy creeps into our conversation. The years pass, hope fades for Cyprus; he refuses to visit Kontea again till “after the solution,” says Hambis – but he doesn’t expect there to be any solution, not since Crans-Montana. (That said, he has many Turkish Cypriot friends, both other artists and the old inhabitants of Plataniskia.) Now he’s single too – though in fact he and Hélène divorced a couple of years ago, “in a very civilised way”, they just continued living in the same house.

Even his success doesn’t mean what it used to, as a younger man: “It used to be something, to say ‘I’ve got work hanging there’ or ‘I’ve had exhibitions in this and that country, or this and that Biennale’. It used to have value for me. Now I just think ‘So what?’.” But it does mean something, I protest: it shows he’s known in the world, not just Plataniskia. “Actually,” replies Hambis acerbically, “I’m known all over the world except Plataniskia!” He laughs and sips his coffee, surrounded by birdsong and a lifetime of persistence.

Click here to change your cookie preferences