In a low-key prominent Limassolian who has led the biggest cultural hub on the island for over 20 years, THEO PANAYIDES finds a woman open to new ideas, and experiences

Everyone knows Georgia Dötzer, at least by name – partly because of the unusual surname, bequeathed by her German ex-husband (she’d probably be less recognisable had she reverted back to Georgia Georgiou). Limassol is vying to be the European Capital of Culture in 2030, and Georgia is vice-chair of the board of directors spearheading the campaign; the team is made up of “prominent persons from Limassol,” she tells me – and it goes without saying that most would place Georgia herself, director of the Rialto Theatre since 1999 (with a three-year break as artistic programme director of Pafos 2017), in the same company.

The three-storey house is ostensibly that of a prominent person, high on the hill in Ayia Fyla with a panoramic view of the city – but in fact it’s quite an old house, built in the mid-00s after her divorce (her ex lives nearby; their son Alexander has a studio flat on the top floor), long before property prices went haywire. The living room is adorned with paintings by acclaimed local artists, as you might expect in the home of a culture maven – but there’s also a temporary cage with six Dalmatian puppies, whose excitable yapping threatens to overwhelm our interview. (Their mum Aila is also in a cage for the duration of my visit, looking like she might be in the throes of post-partum depression.) The whole vibe is agreeably messy, pomp and pretension notably absent – which is not to say she isn’t stylish, coiffed and suntanned, having just returned from a sailing holiday in Greece and about to rejoin the Rialto for what’s going to be her last year in charge; she’s due to retire when she turns 65 in February. She seems younger, I note truthfully – and she nods briskly, with an air of having heard it before.

The Rialto is unique in Cyprus, both for the scope of its cultural programme – it hosts a half-dozen annual extravaganzas, including Cyprus Film Days in April and the Cyprus Contemporary Dance Festival in June – and the relative freedom with which it operates; “For a long time the Rialto had some leeway,” as Georgia puts it, “meaning it could do things without being dependent on economic factors”. It’s also the rare case of Limassol standing up for its past against the steamroller of development. The old Rialto cinema, built in 1930, had been a meeting point for decades – but by the early 90s it was ailing, marooned in a sleazy neighbourhood with cinemas closing down everywhere, and the decision was taken to tear it down and turn it into a parking lot.

Celebrating 20 years with the Chairman and the Minister of Finance

Nowadays, such a project might be par for the course (though probably not for a parking lot); the venerable Curium Palace hotel was torn down a few months ago, notes Georgia ruefully, and no-one protested. At the time, though, the anticipated loss of the Rialto seemed a step too far, like the last asthmatic gasp of the ‘old’ Limassol. The equally iconic Theodosiou warehouses were slated for demolition around the same time – and an outcry had ensued, but too late to save them. In the case of the Rialto, the outcry was more successful: protests and petitions were organised, political parties (on the left) got involved – and the abandoned building was bought, in 1991, by the Limassol Cooperative Savings Bank, which refurbished it then opened it to great fanfare in 1999. 40-year-old Georgia was its first director.

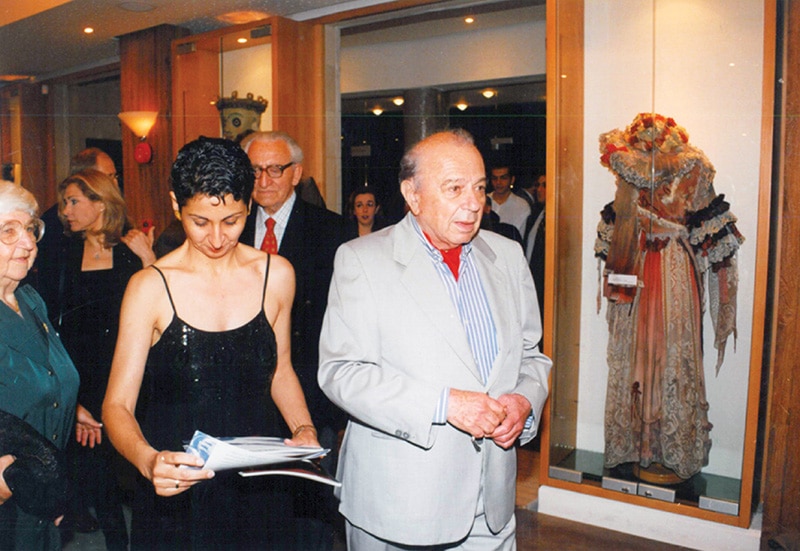

At the inaugaration of Rialto with Cacoyannis and Theodorakis

Why her? It’s a reasonable question. After all, though she’d done a course in Cultural Management during her student days, she didn’t have much experience in administration – just six (successful) years at Ethal, a theatre company that had fallen on hard times. Before that she’d spent her late 20s and early 30s teaching German as a foreign language, having returned from West Germany where she’d spent nine years studying and teaching while also falling in love with Peter, her husband. There’s a photo of her with Michael Cacoyannis at the grand opening – which was grand indeed: Mikis Theodorakis presented a brand-new piece, backed by a symphony orchestra flown in specially from Romania – looking somewhat young and unglamorous, her hair cut boyishly short. She doesn’t look like the director of the biggest cultural hub on the island.

Then again, maybe that was the idea – a breath of fresh air, a change from the usual luvvies and professional culture vultures. Georgia Dötzer is an interesting case of a person who’s drawn to the arts temperamentally – in terms of her vibe, her whole outlook – but not for any other reason. She has, she admits with a laugh, absolutely no artistic talent herself (she can’t even play an instrument). People in the arts often come from an artistic family – but Georgia’s dad was a police officer, and neither of her parents had any interest in culture. Many cultural curators and gatekeepers work single-mindedly to nab high positions at places like the Rialto – but Georgia has never been especially career-driven, or money-driven. Her ex was the same, she recalls: “We both belong to the category of people for whom our career happened by chance, so to speak”. It was his idea to live in Cyprus (he loved the sea, and wanted to be near it; Georgia herself might’ve been happy staying in Germany), then he found lucrative work in shipping companies before taking early retirement at 55 – but, as with her, there was never a plan. “We didn’t set out to have a career, and certainly neither of us looked for a career – least of all in my case, perhaps – where we’d make money, or live a luxurious life. We had other priorities.”

Such as?

“Our freedom,” she replies. “Our ability to choose. Our independence. To enjoy the things we wanted to enjoy, without caring what other people thought.”

What particular talents did she bring to the job? Hard to say – but she’s very much a connector, which you have to be when running a theatre; she seems to know everyone, and not just by name. We’d met once before, quite briefly, in 2021 – but of course my phone number is among her contacts, and she greets me warmly when I call to request an interview. I also take the opportunity to ask if she could recommend other interesting people on the Limassol arts scene, for profile purposes – and she instantly rattles off a list of names and numbers. Her demeanour is buoyant in general: “I had all this optimism and enthusiasm,” she recalls of her time at Ethal – “because I think I’m an optimistic person. It grows less with age, the optimism, but it’s still one of my characteristics”.

That said, she’s not overly sociable. She hates crowded beaches, and avoids glitzy parties. Her tastes aren’t quite mainstream, in life or art. As regards the latter, she’ll attend plays, exhibitions and concerts three or four times a week – even beyond her mandatory attendance at the Rialto – but with an emphasis on “up-and-coming and independent artists, because I feel the need to support them more”. As regards the former, “I don’t like things to be too organised”. Her personal style is informal. She’s hazy on dates, the precise what-happened-when of her life. She’ll always tend to root for the underdog. Her post-retirement plans (or at least desires) include a backpacking trip with her best friend, an organic farmer. “I try to preserve a more alternative lifestyle,” she muses. “Though actually I don’t think I ever abandoned it.”

Much as I hate to disparage our common hometown, Limassol is probably a better fit for her than Nicosia. (She’s lived there since she and Peter came back in 1984.) It is, after all, “a very cosmopolitan city”, and always has been. “It’s an open city, its people are open. You won’t find” – she hesitates – “I won’t say ‘snobbery’, but you won’t find the introverted style you find more often in Nicosia.” It’s a bit of a stereotype, she admits, but it does exist, the whole vibe where “one group meets here and another group meets there and the two never come together. In Limassol you’ll find everyone everywhere”. And of course there have always been foreigners: British soldiers before the invasion (there’s an entire area known as ‘Naafi’, even now), Lebanese in the 70s and 80s, Germans, Russians, now Chinese and Ukrainians. She’ll see them in the audience, especially at classical-music concerts – and foreign impresarios sometimes ask to rent out the theatre to import some celebrity, invariably planning to charge high prices, but the Rialto doesn’t do that; they have “a different philosophy,” explains Georgia, in keeping with their left-wing roots. “We want to be an inclusive theatre, a theatre that’s accessible to all… For us, the aim is to develop an audience, giving young or vulnerable people the chance to watch performances at low prices.”

That’s a whole other can of worms, of course – the fact that, despite their best efforts (and low ticket prices), the local audience remains sadly limited. They get school trips at Rialto, reports Georgia, and she’ll ask the kids about art; very few know or care anything – or, if they do, it’s because they themselves have some talent, so they might learn guitar “but they won’t take the next step, which is to go to a guitar concert”. She herself is proof that it can happen – that an ordinary, slightly mischievous, un-artistic girl can grow up in a “traditional” family yet end up adoring not just art, but unusual art. “I don’t want to be thought of as highbrow,” she says emphatically, “I don’t think I am… But I am open.”

Why is her kind of openness – that alternative worldview she seems to embrace without even trying – so rare? “There’s a split in our society,” replies Georgia – a “one-sided development” that privileges money (and hard work, she adds fair-mindedly; it’s not like making money is easy) at the expense of culture. Limassol, again, is relevant here – and we could talk for hours about the skyscrapers and unchecked development in the wannabe European Capital of Culture, though she isn’t, she makes clear, against progress; she just wonders why the tall buildings couldn’t have been located in some purpose-built ‘new city’, instead of the town’s historic centre. “I have to say that sometimes, when I’m driving in from Nicosia and I come face-to-face with Limassol, I get sad,” she admits. “Others might feel happy but I’m sad. I’m like, ‘For goodness sake, you almost don’t recognise this place anymore’.”

She’s low-key, for a prominent Limassolian. It’s no surprise that a woman so un-pompous – a woman who shuns big events, and spends a chunk of our interview arguing with Mimi (Mimi is a dog) – would feel alienated by the pomp of colossal towers and Dubai-on-the-Med. The years at the Rialto were so “full of light,” muses Georgia fondly – especially the first years, so much creativity and excitement it was overwhelming, “maybe you even neglected your personal life a little”. She’s been there for 21 years, not counting the three in Paphos; 21 is a special number, a coming-of-age number – and she’s happy for the theatre to continue as a grown-up without her. “I want to have fewer ‘must’s in my life, and more ‘want’s. And more time to myself, finally.” I walk down to my car, the noon sky shimmering with heat and Limassol – her project, one way or another, of the past two decades – spread out before me.

Click here to change your cookie preferences