By Michael Martina and Greg Torode

When Chinese President Xi Jinping met executives for dinner on Wednesday night in San Francisco, he was greeted with not one, but three standing ovations from the US business community.

It was one of several public relations wins for the Chinese leader on his first trip in six years to the United States, where he and President Joe Biden reached agreements covering fentanyl, military communications and artificial intelligence on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit.

All three were outcomes the United States had sought from China rather than the other way around, said two people briefed on the trip.

But Xi appeared to have achieved his own aims: earning US policy concessions in exchange for promises of cooperation, an easing of bilateral tensions that will allow more focus on economic growth, and a chance to appeal to foreign investors who increasingly shun China.

China’s economy is slowing and earlier this month it reported its first quarterly deficit in foreign direct investment. And the ruling Communist Party has battled political intrigues that have raised questions about Xi’s decision-making, including the sudden and unexplained removals of his foreign minister and defence minister.

“If the US and China can manage their differences … it will mean that Xi Jinping doesn’t have to divert all of his attention to that (bilateral relations),” said Alexander Neill, an adjunct fellow at Hawaii’s Pacific Forum think-tank.

“He needs to focus on his domestic agenda which is incredibly pressing.”

DROPPING SANCTIONS FOR COOPERATION

Securing Xi’s promise of Chinese cooperation on stemming the flow of fentanyl to the United States was high on Biden’s to-do list for the summit. A senior US official said the agreement under which China would go after specific companies that produce fentanyl precursors was made on a “trust but verify” basis.

In return, the US government on Thursday removed a Chinese public security forensic institute from a Commerce Department trade sanction list, where it was placed in 2020 over alleged abuses against Uyghurs, a long-sought diplomatic aim for China.

“This undermines the credibility of our entity list and our moral authority,” said a spokesperson for the Republican-led House of Representative’s select committee on China.

On top of that, Biden’s Republican opponents argue the US is missing an opportunity by not leveraging China’s flagging economic momentum for more diplomatic gains.

Biden also touted as a success an agreement to resume military dialogues cut by China following then-US House speaker Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 trip to Chinese-claimed Taiwan.

But while Beijing would welcome lower tensions, this is unlikely to change Chinese military behaviour the US sees as dangerous, such as intercepts of US ships and aircraft in international waters that have led to a number of near-misses.

“China fears hotlines could be used as a potential pretext for a US presence in areas it claims as its own,” said Craig Singleton, a China expert at the Foundation for Defence of Democracies in Washington.

Biden administration officials have acknowledged that creating functional military relations won’t be as easy as semi-regular meetings between defence officials.

“This is a long, hard, slow slog and the Chinese have to see value in that mil-mil before they’ll do it. That’s not going to be a favour to us,” one senior Biden administration told Reuters in October in the run-up to the Xi-Biden meeting.

PARTNER AND FRIEND?

In his public remarks to Biden, Xi suggested China sought peaceful coexistence with the United States, and he told business leaders China was ready to be a “partner and friend” to the US, words partially aimed at a business community alarmed by China’s crackdown on various industries and the use of exit bans and detentions against some executives.

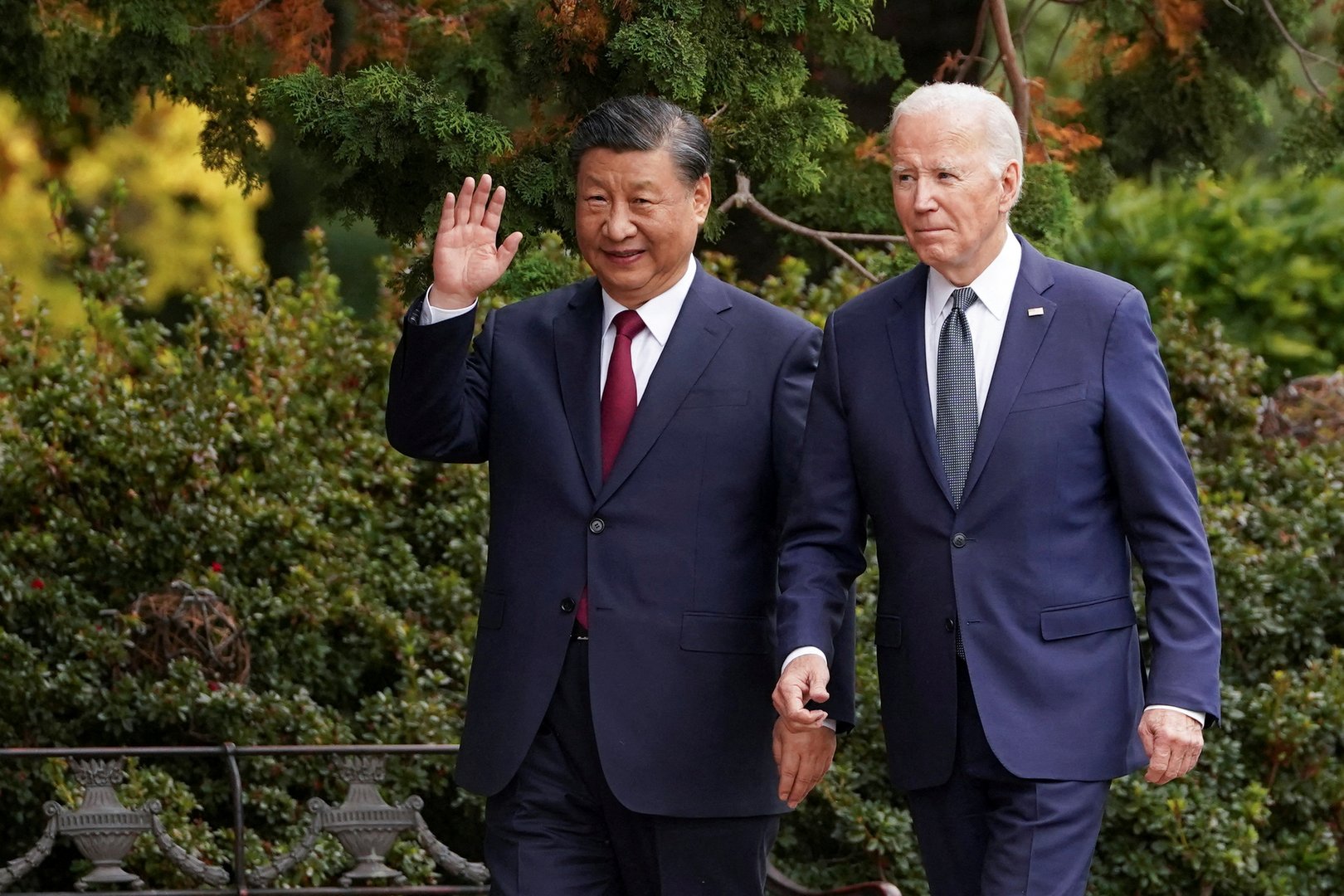

Similarly, Xi’s televised garden walk with Biden, and the largely respectful reception given to Xi by his American hosts, was highlighted in China’s tightly controlled media to show a domestic audience that their president is managing the country’s most important economic and political relationship.

“Xi Jinping may have made the calculation that overhyping the American threat does China and his standing in the party and the party itself more harm than good,” said Drew Thompson, a former Pentagon official who is now a scholar at the National University of Singapore.

“The fact that we are debating whether China is investible is a real problem for China.”

At the same time, Xi reiterated to Biden points that he made earlier this year to Russian President Vladimir Putin, urging the US president to view US-China relations through “accelerating global transformations unseen in a century.”

Analysts say that is code for the belief that China – and Russia – are remolding the US-led international system.

Still, this time pragmatism may have outweighed ideology.

China recognises it’s still necessary for its economic progress to have somewhat normal relations with the US and Western countries, said Li Mingjiang, a professor at the Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“It’s the fundamental driving force behind the meeting.”

Click here to change your cookie preferences