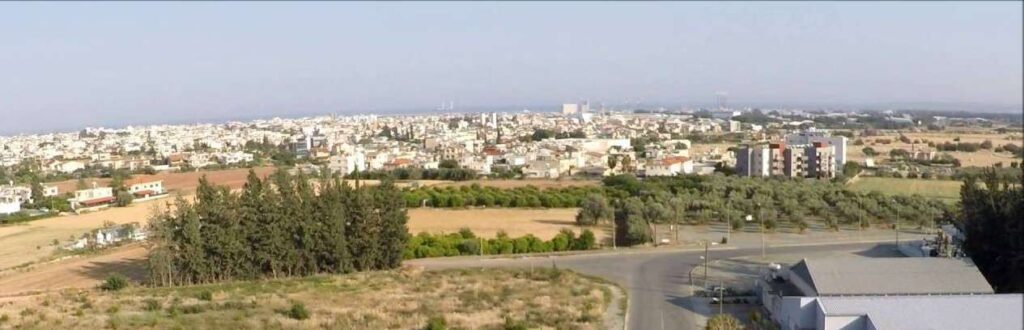

A family ignored the sneers of friends and escaped the noise, haste and cost of Limassol to friendly, peaceful, affordable Ypsonas. But now the city is following them

By John Ioannou

Just over a year ago, one of the large vacant plots on Ilia Kannaourou street, Ypsonas’ main throughway, suddenly came alive with activity. Fencing went up, diggers moved in, and an ant’s hive of purposeful looking workmen swarmed over the site in their hard hats and hi viz vests.

As they usually do in a small town, people began speculating on what might be being built. My barber thought it could be a smart new apartment complex with large shops on the ground floor. Ypsonas is growing fast as land here is cheaper than in Limassol, so young families from other parts of town often end up here after being priced out of their local areas. It would make sense, he said, as he buzzed my fade. There isn’t enough housing nowadays, and not enough retail space on the main road where any vacant shops are always snapped up quickly. I nodded in agreement.

Ypsonas is not quite a suburb of Limassol, not quite a growing village, and not quite a stand-alone town. It has elements of all three, as it lies close to Limassol on its western flank, has an old village centre which used to be the main hub but is now mostly occupied by migrants crammed into run-down houses, and is governed by an independent municipality operating out of an impressive new town hall.

While the area has grown rapidly in recent years there is still a strong sense of community and the place still feels very Cypriot in contrast to other, more gentrified parts of town. Step into the local supermarket or pharmacy and you will bump into your friends and neighbours as opposed to the dour faced xenous encountered in wealthier Linopetra or Ayios Athanasios who speak no Greek. Our schools here are fine with no need for nosebleed private fees, and the new dimotiko up in Ypsoupolis provides the local children with an excellent base from which to move on to the gymnasium across the street.

Ypsonas may have had a bad reputation during the 1990s for being too close to the organised crime hotspots of Kolossi and Trachoni, but it is perfectly safe and the people unfailingly courteous and kind. The town was originally founded by inhabitants of the villages of Lofou and Koilani, and they are friendly and grounded people who greet you warmly and remember your children’s names whenever they see you in Zorpas. Problems are efficiently handled by the municipality, who cover a large area with limited manpower, and you can even WhatsApp the deputy mayor with a complaint about garbage trucks driving too fast down your street and he will sort it out with a quiet word.

All in all, it’s a good place to live and raise a family; close enough to town to commute, close to the town’s best beaches and with enough facilities that you never really need to go anywhere for anything. The people are working class and lower middle class: schoolteachers and civil servants, small business owners and office workers, with the odd lawyer or bank manager thrown in. Living here we are incredibly happy.

Back in the day some of our so-called friends at the time recoiled when we told them we were moving to the wild west of Limassol, and shook their heads in disgust. It’s too far, they said. Too rough. Full of black clad bearded guys driving around in double cabins. The schools are crap, and the kids will need to come in and go private. Why would you want to live over there?

But to our growing family it was a blessing to find an affordable plot where we could build a house and have a garden, with space enough to plant fruit trees and set up a trampoline and a plastic pool for the kids. We had long dreamed of escaping the noisy old apartment buildings of the city, the cheapskate neighbours who would not pay their common expenses, the peeling plaster and damp walls. My wife could not stand the cold tiled floors during the winters in those uninsulated apartments with the single pane windows, and made me take a blood oath to wrap our new house in eight centimeters of EPS. I had also reached the end of my patience, tired of every idiot dragging his chair across the floor at 3am while his wife clacked around in high heels. Time to go.

My dad flew in with a 20k injection from BOMAD and we scraped together whatever other savings we had. Once the plot was ours, a low-interest mortgage from the state housing corporation allowed us to build just enough house to move into. It was plaster grey as the money had run out before we got to the outside finishes, and it sat in a sea of yellow mud, but we didn’t care. We had found freedom and peace. Siga-siga we would finish the rest. We settled in and did our best to become Ypsoniates.

At the time I felt that our journey was very personal and unique, but in retrospect I realise that we were following a well-trodden path, carved out by many upwardly mobile families before us. My neighbour, a university lecturer who farms goats on the side, nodded sagely when he saw us moving our stuff into the half-finished house.

“We did the same back in the 80s,” he said. “Ours didn’t even have windows upstairs.”

I am glad I ignored the sneers of our then-friends, as moving my family to Ypsonas was one of the best decisions of my life. In practical terms, it did not stretch our budget too much, as cheaper land meant we had enough left over to build a home without mortgaging ourselves to the hairline. But it was more than just euros and cents, it was a sense of finding somewhere to put down roots. I knew the plot and the area were perfect, even before I stepped out of the car to greet the estate agent. I could already picture us living in this green and open area well above the highway, quiet and still but only minutes away from the schools and shops. There are wide sweeping views over the Akrotiri peninsula and the coast, with fresh westerly breezes during the hot summer. The neighbours are great and we even have a few farms within walking distance where we can buy fresh eggs and honey. Our kids love their schools, have many friends and feel like they really belong here. As a parent you cannot really ask for more.

As the weeks went on, the new building on our main road kept getting bigger and taller, eventually towering far above the local shops like the Ikoagora discount store and Andros Hair Salon and the Creperie-de-la-Melis. By now it was well known that this was no modest apartment building but a huge office complex that would house the new Cyprus headquarters of one of the biggest shipping companies in the world.

The corporations were creeping west out of Limassol, and we had seen early adopters of this trend in the previous decade as a few big firms moved out of the centre to build headquarters in Polemidia and Zakaki, all a stone’s throw away from Ypsonas. But this new building would be different: seven floors, multiple sub levels of parking, and office space to house perhaps a thousand staff. Our mayor, a die-hard communist, had a vision, and this first big investment would empower other mega-firms to follow suit and transform Ypsonas from a scruffy suburb into a modern and affluent district awash with international capital.

Each night I crawled through traffic past the new building whilst taxiing my children between their activities, and I began to wonder.

Having worked for corporations for most of my life I knew a little about them. They were well-organised and usually provided good jobs in structured and professional environments, so it was logical to assume that the new building would offer opportunities for the local residents and stimulate the surrounding economy as workers spent money in nearby coffee bars and grocers.

I thought back to when I worked for a family-owned ship manager in central Limassol years ago. Our coffee was ordered from an old lady down the street, who sent her husband to deliver skettos and frappes with a round silver tray hanging on three chains. We ordered sandwiches from another shop on the corner. ‘Dirty sandwich’ meant hot and greasy with lountza and loukaniko, while ‘clean’ referred to untoasted with halloumi and tomato. Even our non-Cypriot colleagues learned enough Greek to order by phone (‘Ermina mou, enan dirty separakalo?’) and the local grocer-cum-periptero had a steady stream of business all day as we took breaks to stretch our legs and grab twenty Crown or a can of Sprite. Even the local gyms benefitted as some of us used the long and strictly enforced lunch break to work out, shower and be back at our desks in time to ruin the calorie deficit with a hot and dirty.

Those were the days. Today, many of those traditional family-run ship managers have evolved into private equity funded corporations with large and impressive new premises. And as the competition grows, they are keen to provide first-rate benefits to attract and retain staff. This means subsidised canteens, well-equipped gyms and high-quality coffee machines all on site. Staff no longer need to leave the building at all, which, I suppose, is the entire point. They sit firmly ensconced in their five-star office blocks, happy to be fed and watered, all needs comfortably met within the building’s perfectly calibrated ecosystem.

So pity the local small business owner hoping to earn a living off those well-paid office workers.

But what about jobs? Well, maybe. But corporations hire on competence and any new intake will be made based on experience and ability rather than location. Those employees will also need to commute in and out of Ypsonas, adding hundreds more cars to an already clogged and badly designed road system. Ilia Kannaourou Street has zero pavements and is a death trap at night, especially in winter. On this dark and poorly paved main artery it is easy to miss a rain-drenched migrant walking by the side of the road or a stoic delivery driver pushing their moped to the limit before the app flags them as late and they lose their five-star rating. Traffic has already increased in the last few years as more exiles like my family move west, and while the municipality is trying to mitigate this with a fleet of brand new electric buses, nobody is quite sure yet where they go and if they want to risk getting on them.

Property prices will also be impacted and Ypsonas could cease to be the affordable side of town, no more a place where young families still have a fighting chance to buy a home. Corporations have tiers of well-paid staff, some of whom will opt to move closer to work, and land owners across Ypsonas will feel justified in asking for inflated prices, pointing toward the towering new building as evidence for their demands.

Property prices and rents in Limassol are already too high, so we would be better off designating areas like Ypsonas as residential where families can continue to settle and raise their kids. We should be focusing on proper infrastructure, parks, decent and affordable housing and transport, even a good taverna or two.

Limassol is still relatively small, and skyscrapers do not need to spill over into the suburbs. They are better located in some kind of a Central Business District like the one proposed for the karnayio waterfront area, with regular public transport links and focused high-end services.

And while we are at it, why are we even constructing more massive office buildings to begin with? The pandemic proved that things work just fine with staff on a hybrid model where office days can be hot-desked in smaller premises by happier employees who spend less time commuting and more time with their families.

As the traffic piles up, the potholes get deeper and the new building grows ever skyward, it feels like the city is reaching out to pull us back in. The new stadium in Ypsoupolis has already brought more traffic and congestion to our doorstep, and on match days I can hear the fans roaring inanely at one another as I water my garden. I joke to my barber that if this continues, we will all end up moving back to Koilani and Lofou just to escape the traffic and the noise. But is there really anywhere left to go?

On our brave new island of skyscrapers in villages and casino resorts in protected wetlands it would only be a matter of time before those greedy tentacles crept out to find us again. Someone once said that without deviation from normality, progress is impossible. But by destroying normality, regression often becomes inevitable. In Ypsonas at least, I really hope we wise up fast and realise that some things are best kept as they are.

Click here to change your cookie preferences