The July 1974 coup and subsequent Turkish invasion of Cyprus were tragic in themselves but what’s even more tragic is that 50 years later, the prospects for a solution are at the lowest they’ve ever been.

The July 15 coup plotters’ short-sighted and disastrous goal to overthrow Archbishop Makarios gave Turkey the excuse to invade the island five days later and ultimately seize almost 37 per cent of the island.

This renders the coup to overthrow President Makarios even more unforgivable though it is often glossed over in the public domain, overshadowed every year by the subsequent July 20 invasion anniversary. Thousands dead and missing, hundreds of thousands displaced, rapes, torture, POWs, mass killings and burials, population shifts, terror, loss, poverty and the economic devastation of an entire country as the Turkish army fanned out from Kyrenia with nothing and no one to stop them.

This was what was set in motion that Monday morning on July 15 when the air raid sirens blared at 8.20am. Coincidentally, the two 50th anniversaries of the coup and invasion fall on the same days of the week they did in 1974.

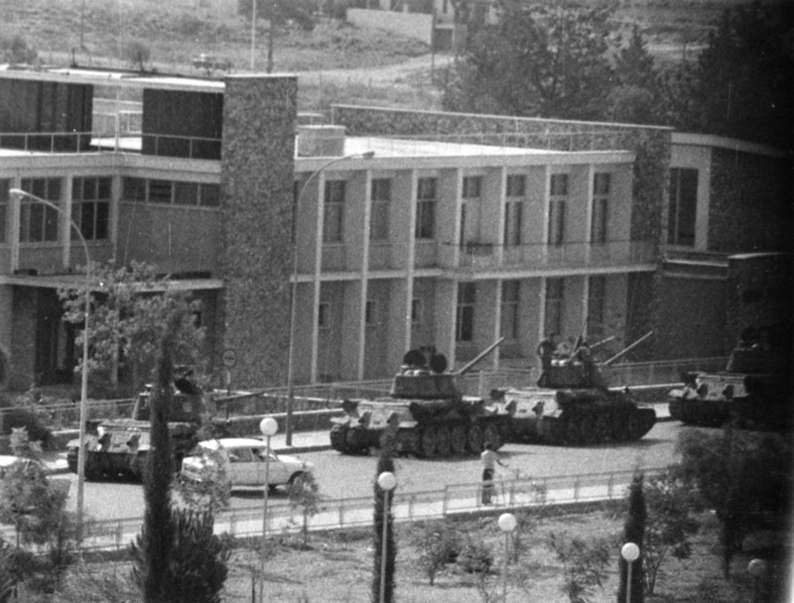

Backed by Greece’s junta, rogue National Guard units and members of the Eoka B paramilitary group manned columns of tanks that rolled down the streets of Nicosia and headed for the presidential palace where Makarios was meeting with a group of Egyptian children.

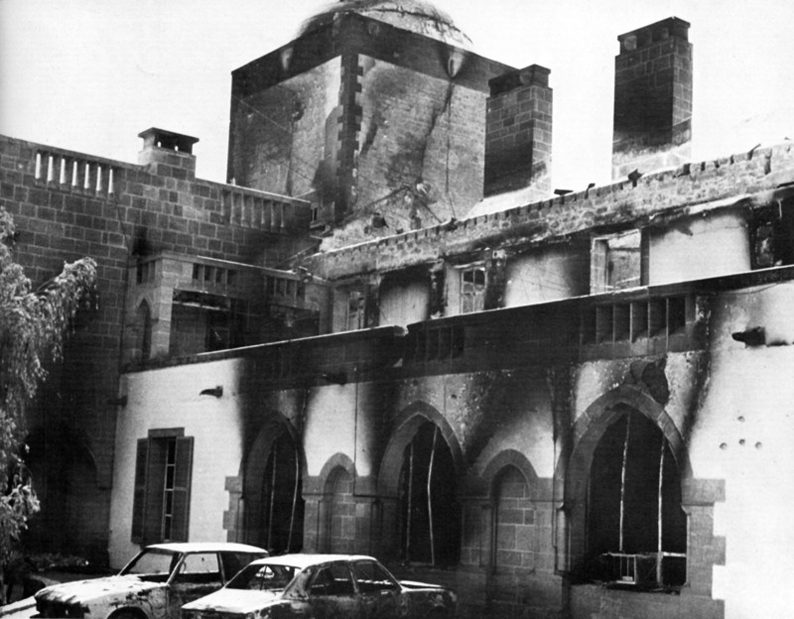

The meeting was interrupted by gunfire and Makarios was led away by his minders down a passage on the side of the compound that was left unguarded by the coupists. The palace was heavily damaged in the attack.

Via a tortuous route, Makarios fled to Paphos, where the British managed to retrieve him in the afternoon of July 16 and the RAF flew him from Akrotiri to Malta on a transport plane, and from there to London the next morning under what was known as ‘Operation Skylark’.

Early July 15 in Athens, using the slogan ‘Alexander has entered hospital’, the head of Greek military forces in Cyprus Brigadier M Georgitsis announced to the leadership of the Greek junta the start of the coup against Makarios.

Between 8am and 9am, the coup leaders, after taking over the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation, proclaimed victory saying “The national guard intervened in order to solve the problematical situation. […]. Makarios is dead.” However, being whisked off by the Brits, Makarios announced that he was alive from a private broadcast in Paphos.

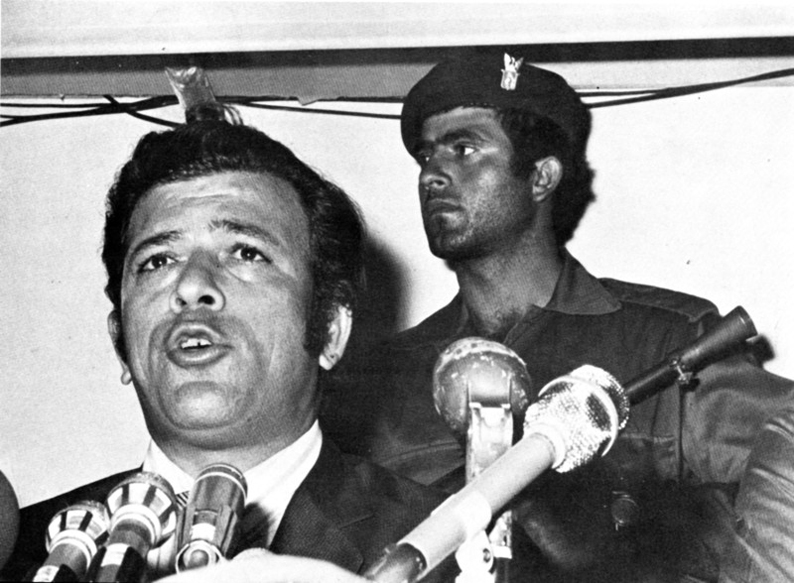

On the afternoon of July 15, Nicos Sampson, a divisive former Eoka fighter and journalist who was feared by the Turkish Cypriots, was installed as president by the coup leaders, but only after the offer of the top job had been rejected by several others including House president Glafcos Clerides. Sampson’s presidency only lasted eight days, earning him the moniker Oktaimeros, which roughly translates to “the eight-day man”.

The new regime heavily censored the press and Sampson focused on suppressing any support for Makarios. According to official government data, 98 people were killed during the coup.

Only Sampson stood trial and was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 1977. Three years into his sentence he was allowed to go to France for medical reasons and remained there in exile until 1990 when he returned to prison in Cyprus but was freed again a few months later.

In the 1960s, he led armed groups in fierce battles between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot irregulars and was dubbed ‘The butcher of Omorfita” by Turkish Cypriots.

The Cyprus Mail was one of the last interviews he gave the year before his death from cancer at age 66 in May 2001. He did not have anything memorable to say other than: “I swear to you, I never killed a Turk… in cold blood”. Despite his role in the division of Cyprus for 50 years now, hundreds of people attended the funeral. Many believe he was a scapegoat for the real engineers of the coup.

The coupist government collapsed on July 23, on the third day after the invasion began, and along with it ended the reign of the military junta in Greece, which had ruled with an iron fist since April 21, 1967.

Makarios himself was not in Cyprus on July 20. He was in New York where he had gone to denounce the Greek junta before the UN Security Council and to hold meetings with US officials following talks in London. Clerides, as House president, took over as acting president until Makarios’ return in December 1974.

According to the book ‘Britain and the Cyprus Crisis of 1974: Conflict, Colonialism and the Politics of Remembrance’ by John Edward Burke, “prior to the Turkish invasion the US administration gave partial recognition to the Sampson regime, whilst post-invasion American military action against Turkey was categorically ‘ruled out’ despite Britain wanting to take action which it felt it could not do alone. “It was abundantly clear that Britain would not intervene under the provisions of the Treaty of Guarantee. As such Turkey was effectively given freedom to manoeuvre on Cyprus.”

While the politics of the coup and strategic interests occupied officials in far-flung capital cities, on the morning of Saturday July 20 on the ground in Cyprus, British journalist Michael Nicholson was one of the first to see the Turkish planes and parachutists.

In an interview with the Cyprus Mail in 2014, he recounted how he stood on the dusty plains outside Nicosia pointing to the sky and announcing to the world on camera: “It’s 4 minutes past 6 and the first of the Turkish troops have landed in Cyprus. About five of these aircraft passed over in the last five minutes, they were guided in by jet fighters and the very first paratroopers are now hitting Cyprus soil.” The footage remains the most famous visual document of the moment the invasion was launched.

Over the years the footage by Alan Downes and the reporting of Michael Nicholson have become a crucial part of countless documentaries and remain a haunting reminder of that day 50 years ago.

As Cyprus fell into chaos, death and destruction, then British Foreign Secretary James Callaghan spearheaded efforts aimed at brokering a ceasefire, which was achieved on July 22. The Turks had already established a foothold in Kyrenia which they managed to link to the Turkish Cypriot enclave in Nicosia, accounting for around 10 per cent of territory.

The UN Security Council also met on the day of the invasion and adopted resolution 353 by which it called upon all parties to cease firing and demanded an immediate end to foreign military intervention.

However, despite the ceasefire, fighting resumed on July 23, especially in the vicinity of Nicosia international airport, which, with the agreement of the local military commanders of both sides, was declared a United Nations protected area and occupied by Unficyp troops under whose control it remains to this day.

Eventually, at a conference of the guarantor powers (Greece, Britain and Turkey) in Geneva from July 26 to 30, agreement was reached on establishing a security zone between the now occupied areas and the territories still under the control of the Republic of Cyprus. It was also agreed to hold another conference in early August, again in Geneva, with the participation of President Clerides and Rauf Denktash, representing the Turkish Cypriots in order to discuss the new constitutional regime for Cyprus.

But Turkey wasn’t done yet.

The Geneva conference on August 10 failed, collapsing on August 14. The Turkish army immediately moved forward on two fronts, going on to capture close to 37 per cent of the island’s territory.

Callaghan had thought he could foil the second wave. Subsequently, however, he came to realise that the Geneva conference was always going to fail. “At that point, I did not suspect, as I do now, that the Turks regarded the conference as little more than an opportunity to secure more time and diplomatic cover to prepare for a second attack.” he wrote in a memoir.

Two weeks earlier in a meeting with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Washington, Makarios had tried desperately to persuade the American official to rein in the Turks, warning them of Ankara’s continued push to gain more ground.

Kissinger replied: “Turkey is not advancing any further” to which Makarios countered: “What disturbs me is that the Turks will not be in for settlement. As time passes they will be consolidating their position there. The talks will take months or years…”

The archbishop, who eventually returned to a broken Cyprus in December 1974, and died on a now-divided island in August 1977, probably didn’t imagine that those “years of talks” he spoke of would turn into at least half a century of failed negotiations.

Click here to change your cookie preferences