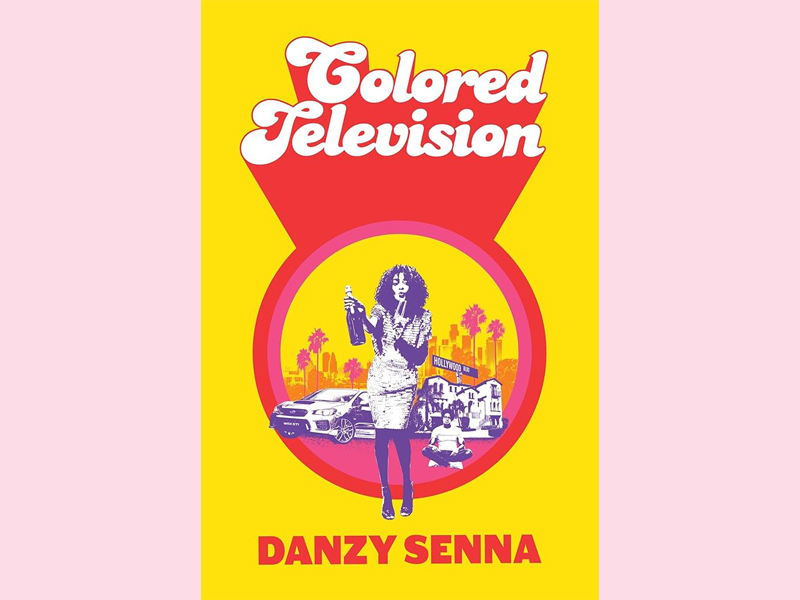

There are times in life when what you really need is an expensive psychic to tell you ‘This is bigger than you and your silly heteronormative daydreams, Jane. This is about the universe. And trust me, you don’t want to fuck with the universe because that bitch has no mercy.’ Sadly, Danzy Senna’s latest novel is set in LA, which makes sense because if you could imagine the kind of expensive psychic who might say that existing anywhere, it couldn’t really be anywhere else. The good news is that Colored Television lets you live vicariously in this world, for better and for worse, in a book whose dialogue is regularly as sharp and funny as Wesley the psychic’s cutting directive.

The Jane receiving Wesley’s spiritual guidance is Jane Gibson, a mulatto novelist and lecturer nine years into her writer’s sophomore slump, and the ‘this’ that she is so forcefully told not to ignore is Lenny, a black painter who refuses to paint ‘black themes’ and consequently sells no paintings. Jane listens to Wesley, marries Lenny, has two children, and ends up leading an itinerant life around LA due to lacking the money to settle down. A child of bohemian, artistic parents herself, Jane simultaneously takes pride in her own creative goals, working on a vast trans-historical novel following the mulatto throughout the life of America, and yearns for ‘a real middle-class home the way only a half-caste child of seventies-era artistic squalor wants a home’.

Lenny, having been born into affluence, takes artistic poverty differently. He disdains all sell-outs and assumes that if America won’t buy his paintings, the problem is with America. So, while Jane dreams of a house in ‘Multicultural Mayberry’, Lenny wants to move the family to Tokyo, site of his upcoming show. It is this clash of pasts and ideal futures that drives the family drama and leads Jane to lie when she seems to be making headway on securing their future by turning herself into a screenwriter.

What Senna does so well in this novel is never lose sight of her biting, comic talents that cut hilariously into LA society, TV, race, millennials, and even her own career as a writer whose subject matter is invariably biracial American existence. The dialogue is poised and memorable, and there is always a smile, occasionally a laugh, to offset the precariousness of Jane’s life and aspirations. The one disappointment is that while Senna gains the reader’s emotional investment, she never quite pushes that side of the book home, and the ending lacks the heft that would make a reader carry the novel with them after they put it down. You’ll enjoy it while you’re reading it, though.

Click here to change your cookie preferences