Casting words of praise into the bureaucratic abyss

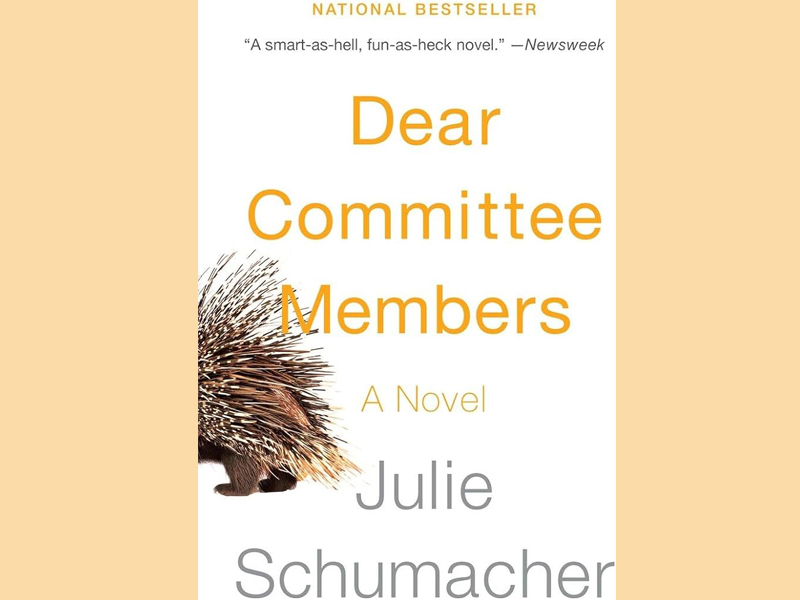

In a recent review, I committed a sin. I referenced a novel that I had not read. As so often, one’s first step into the mire of corruption leads to immersion rather than retreat. On to sin number two: reviewing a novel old enough to have been widely read and widely reviewed. I confess, but I do not repent. Because this short catalogue of error (it would be longer, no doubt, but if there is a reviewers’ catechism, I have not studied it) led me to reading Julie Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members, and I do not have it in me to regret a literary pleasure.

The first in a trilogy focusing on the misadventurous life of Jason – Jay – Fitger, professor of English and Creative Writing at Payne University, Dear Committee Members is an epistolary novel made up of the letters of recommendation that Fitger writes over the course of a single academic year. How many reference letters can one man have to write? Fitger explains it best: ‘I haven’t written a novel in six years; instead, I fill my departmental hours casting words of praise into the bureaucratic abyss.’ And we’re so very glad he does because Schumacher uses the letters to give us unadulterated Jay-time, as he earnestly promotes a protégé, wages futile war on the electronic recommendation form, clumsily alienates an ex-girlfriend, yearns for an ex-wife, pleads for an opportunity that might just get a gifted colleague back on track, and rails against the Economics department whose renovation of the floor above condemns English to ‘intermittent water supply, semioperational light fixtures, mephitic odors, and corridors foggy with toxins’. Not to worry, though, Fitger is ‘sure our foreshortened life-spans will be made worthwhile on the day when the economists, in their jewel-encrusted palanquins, are reinstalled in their palazzo over our heads.’

The central, ironic perfection of the novel is that the letter of recommendation, at least as shaped by Fitger, is simultaneously selfless and wildly egocentric. He goes to enormous lengths for others, while being unable and unwilling to suppress himself, as we see from the asides, the rants, and the astonishing range of valedictions (can you name a better one than: ‘With candor, regret, and a whiff of vengeance’?). And through it all, we see a man who, despite his own professed and evident misanthropy and dysfunction, emerges as not just hilarious, but tender and wise. Indeed, here is a character, and an author, who powerfully manages to convince us that, just as Fitger believes the world would be a better place ‘If every member of the human race evinced a fondness for literature’, the world would also be better if it had more Fitgers in it.

Click here to change your cookie preferences