A pioneering trial in Cyprus aims to find out

A new initiative is testing the use of underwater drones and artificial reefs in marine conservation at the Ayia Napa marina.

Set to launch at the end of the year, the project, led by the Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute (CMMI), will explore new ways to monitor marine ecosystems to address issues of pollution, habitat destruction and the impact of human activity by implementing a system called Eonios.

CMMI aims to use this approach to support sea repopulation efforts while easing the pressure on protected areas. By creating new underwater sites rich in biodiversity, the initiative seeks to attract swimmers and divers away from ecologically sensitive zones, reducing the impact of overtourism.

“We have protected areas all over the world – but nobody is protecting them and that’s a big issue,” says CMMI research director Daniel Hayes.

“For the Cypriot ecosystem – particularly the sea – it is very important to keep human pressure through tourism or emissions to a minimum.”

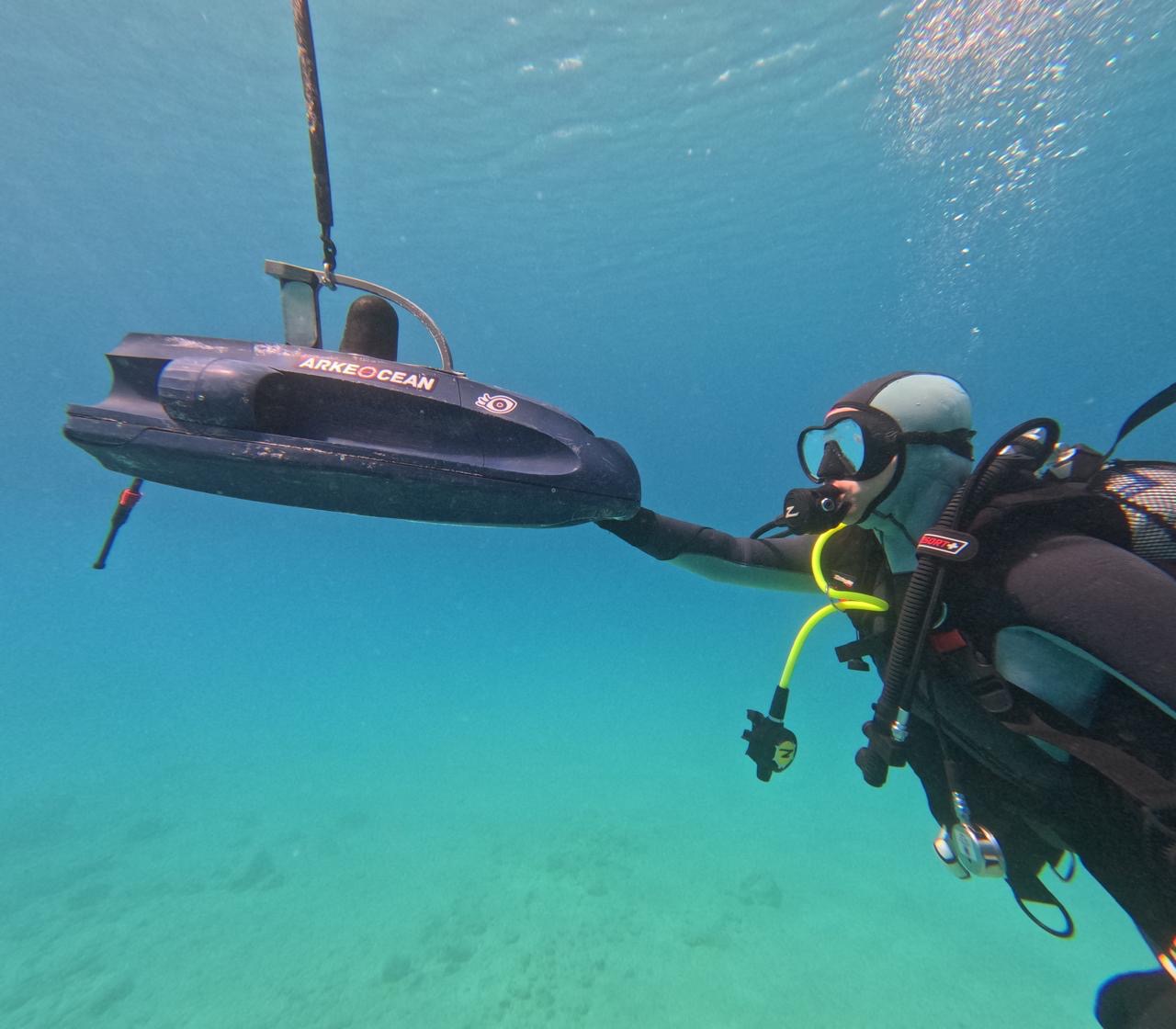

The project combines underwater drone technology with artificial reefs designed to ease human pressure on fragile underwater habitats with two drones.

“The reefs are made in Cyprus, created by our own ‘recipe’,” explains Hayes. They are constructed from a special type of concrete that, according to CMMI, not only avoids harming the underwater ecosystem but may even benefit it.

The structures are then 3D-printed, using scans of natural reefs to replicate features like cracks and holes to encourage marine life. “Sometimes, we even create exact copies of real reefs,” Hayes adds, visibly excited about the “gigantic 3D printer” used in the process. Once printed, the reefs are placed at depths of 10 to 20 metres as any deeper, would be too dark for the drones to monitor effectively.

“The big problem with studying the sea is that it is hard and expensive,” says Hayes. “If we didn’t have the drones, we would have to go by ship.”

Beyond programming, the drones are equipped with sensors and emit a ping sound every few seconds to measure depth, so they can navigate without collisions.

The drones are produced by a company in France that specifically designed and customised them for their intended use in Ayia Napa. As of now, CMMI plans to work with two drones measuring approximately one metre high and 60-70cm wide which will be left underwater.

Since the drones will remain underwater, they require charging which can turn into a challenging task below the surface. They will park in charging stations, that Hayes refers to as industrial-looking “underwater garages”, on top of which the artificial reefs will be placed to avoid disruption to the natural marine environment.

To charge the drones, the garages need to be connected to electricity. This is one reason why the project will initially take place at the Ayia Napa marina, where existing infrastructure for power and internet makes operations easier for scientists.

Other locations, including Limassol, are being considered, but no final decision has been made.

“The further we go, the more expensive it gets, as we would have to provide access to the internet and other infrastructure,” Hayes explains.

CMMI aimed to minimise or not cause harm to any natural habitats. However, if the project proves successful, similar initiatives could be launched in other areas in the future, potentially even near – but never in – protected zones in order to help revive biodiversity.

“We only place reefs and drones in areas that are not vulnerable,” Hayes assures, meaning no installations will be made in sensitive ecosystems such as coral reefs or seagrass meadows.

Operating with sound instead of light or phone signals – as this is very difficult to impossible this deep in the sea – the drones could serve as an extra layer of protection in marine habitats. If placed in protected areas, they could detect illegal motorboats and alert authorities, helping to enforce regulations where constant patrolling is impossible.

Beyond security, they could also offer valuable insights into marine life, tracking the movements of dolphins and orcas on their way between Cyprus and Greece.

“We will be able to hear so many things happening,” Hayes says, emphasising the drones’ potential for observation and conservation efforts.

In Cyprus, artificial reefs have long sparked controversy among environmentalists, fishermen, and those generally passionate about Cyprus’ seaside.

As of now, six artificial reefs have been created as part of a project by the department of fisheries and marine research. These so-called Marine Protected Areas (MPA) were created by sinking several old vessels into the seabed which will supposedly be absorbed by the environment over time.

“Not only are we looking at ways to increase biodiversity, but also to possibly boost non-intrusive tourism,” Hayes says.

While the artificial reefs are designed to support marine life recovery, tourism is also a factor. By creating vibrant underwater habitats filled with corals, fish, and other species, the project aims to attract divers to these areas, offering a less intrusive alternative to touristic activities like jet skiing.

“Artificial reefs will serve as the foundation for the entire food chain,” Hayes explains. “It will build up from the smallest species and eventually attract others.” But with the fish gathering, the reefs could also turn into an attractive location for fishermen, potentially turning the reefs into an unintended fishing hotspot something the project seeks to avoid.

“Most likely the artificial reefs will create a spillover effect leading to fish to spread to other areas which then could also benefit the fishermen,” Hayes says, emphasising that CMMI aimed to work closely with them to ensure a fair balance for both sides.

While artificial reefs aim to support marine life recovery, they are also a response to the growing threats facing Cyprus’ marine ecosystems. Coral reefs exist in both shallow and deep waters, particularly around Paphos.

However, they are under threat due to climate change, mass tourism, hotel and marina construction, and agricultural runoff. Without intervention, they could soon disappear. The CMMI project could help monitor and restore marine life while easing human pressure on vulnerable areas.

Signed in June 2024, the project is set to begin at the end of the year, with the first prototype expected by late 2025. It is funded by the Centre of Excellence, the EU Commission, and the Republic of Cyprus’ Ministry of Innovation.

“This can be a next step in understanding our oceans,” says Hayes.

Click here to change your cookie preferences