By Dimitri Gonis

Friedrich Nietzsche once quipped that ‘God learnt Greek when he wanted to become an author’.

On the April 14, 2025 Unesco agreed with him, formally recognising Greek as “the longest continuously spoken language in Europe… Occupying a key position in intellectual thought, in the linguistic expression and formulation of fundamental concepts and key words of European and wider, almost universal intellectual thought which are conveyed, understood or traced in words/concepts of the Greek language.”

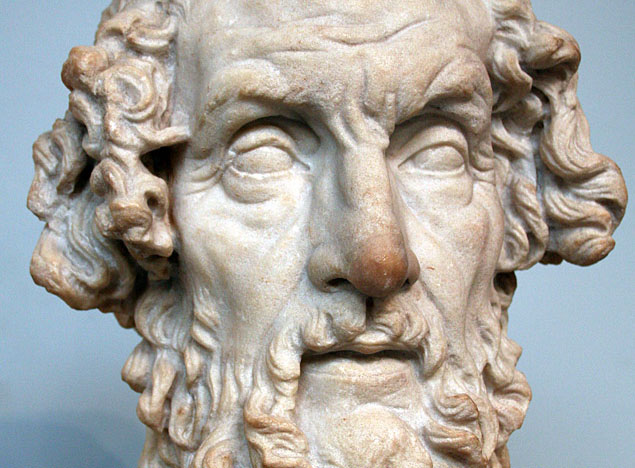

The Unesco declaration befitted the mother tongue of western civilisation, which has left its ubiquitous marks in all fields of our lives. Philosophy, astronomy, medicine, geometry, mathematics, biology, geology, archaeology and many more are fundamentally indebted to Greek. English is replete with Greek vocabulary that people take for granted when they take their children to ‘school’ or ‘pause’ for a moment. Greek brought us myths of the gods, of Zeus, Poseidon, the Trojan War and Odysseus (Ulysses) to Hollywood and popular culture. It is the language of the poet Homer, Socrates, Aristotle and Alexander the Great. Roman emperors penned their thoughts in it. Its recognition by Unesco was a particularly momentous occasion for those of us who love and teach it.

The Unesco’s decision was unanimously reached by all 80 countries comprising the executive committee of the organisation and institutionalises the annual celebration of an International Day for the Greek Language by Unesco and the UN each year on February 9, the day Greece’s national poet, Dionysios Solomos passed away, by all 190 countries.

Today Greek is spoken by approximately 20 million people around the world – in Greece, Cyprus and the diaspora. It is also one of the official languages of the EU. Apart from official Greek, other extant varieties can be found in southern Italy Griko, the Black Sea Romeika, the eastern Peloponnese Tsakonika including Cretan and Cypriot dialects. These varieties are intelligible to any Greek speaker with a strong command of the language – something that attests to its transhistorical resilience and organic nature. Unlike Latin, which is considered a dead language, Greek, even though it underwent various phonetic, grammatical and syntactical adaptations, never ‘died’. Modern Greeks still use the vocabulary their ancestors used albeit with an altered syntax and pronunciation.

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great a different form of Greek, known as Koine, emerged into history as the lingua franca. Very soon after that it would enter history as a ‘sacred language’. Scholars would employ it to translate the Hebrew Bible for the large Jewish community living in Alexandria in the third century BCE. Three centuries later it would become the language of the Gospels and of historians. As a ‘sacred language’ its importance only grew throughout the centuries, becoming the language of Orthodoxy, commerce, and scholarship. For one thousand years it was the official language of the Byzantine Empire. To be educated meant to speak Greek and all the civilisational implications that came with the knowledge of that speech.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century Greek had become firmly entrenched amongst the European aristocracy. European, and mainly British, intellectuals clamoured around the Greek revolutionaries to ‘save eternal Greece’. Poets like Byron joined the Greek struggle, investing his wealth and praising Greece in his poetry. Others, like Lord Elgin, became obsessed with it, stealing its antiquities and taking them back to Scotland so he could bask in the light of their glow and be closer to the ancients. Like Byron, the other great English poet Percy Shelley declared: “We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their roots in Greece.”

Today languages are up against an aggressive culture of anti-intellectualism. One of spread sheets and bottom lines that leaves no room for the romantics of language and language teaching. But we need to bring back humanity into the humanities. What better way to do so than by acknowledging the contributions of the language that has left its undeniable and indelible imprint on our universal consciousness and culture. Unesco’s decision is the ultimate acknowledgment of this, and it is a proud day for all of those who tirelessly invest their lives in the preservation and promotion of this truly beautiful language.

The petition commenced in February 2024 and was led by the Greek ambassador to Unesco in Paris Georgios Koumoutsakos. He was supported by an international team of academics led by professors George Babiniotis (Athens University, Greece), Christos Clairis (Sorbonne, France), Ioannis Korinthios (Napoli, Italy), Anastasios M. Tamis (AIHER, Australia), Philip Trevezas (California State University, USA) and Stella Priovolou (Parnassos, Greece).

I’d like to end this piece with a few of verses from Greek Nobel Laureate, Odysseus Elytis:

Greek was the language that they gave me

A humble home by Homer’s shores

My language is my sole concern

On Homer’s shores

Dr Dimitri Gonis is a lecturer in the Greek Studies programme in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at La Trobe University, Melbourne

Click here to change your cookie preferences