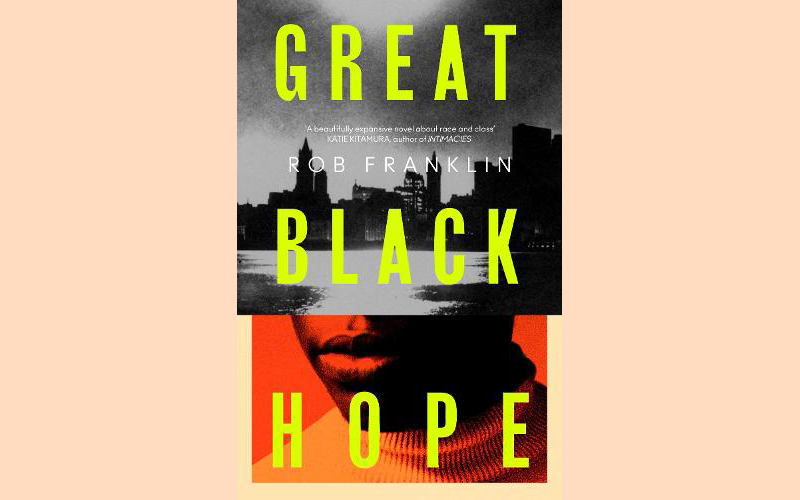

Book review: Great Black Hope by Rob Franklin

By Simon Demetriou

Ideally, I would sit down to write a review the day after I finished reading a book, having had time to ruminate and plan, and for impressions to settle and form themselves in my mind. Often, life and/or laziness get in the way, and I find myself – as on this occasion – with about a week having lapsed since I put down Rob Franklin’s debut novel. Upon sitting down to plan the review, I realised that I barely remembered anything about the book other than that it took me longer to read than a novel of its length should. The conclusion is a sad one, but Great Black Hope is both tedious and forgettable.

The novel’s inciting incident is its protagonist, Smith, getting arrested for snorting cocaine at a party in The Hamptons. The unfolding plot that leads through auditioning and hiring lawyers, a stint in ‘discount, virtual rehab’ with an entertainingly caricatured psychologist whose incompetence vies with his eccentricity and makes Dr Meyers Mancini the most memorable character in the novel, and the final court hearing, runs concurrently with a story that began prior to the novel’s opening: the mysterious death and dumped body of Smith’s best friend and roommate, Elle.

The reader’s great hope is that either of these stories will lead somewhere. Will Smith’s blackness weigh more heavily than his money and privilege in how he is judged? Will the unknown man last seen with Elle and suspected of disposing of her body and, potentially, murdering her, be found? Will Smith be the one to find him? Unfortunately, while all three of these questions are answered, the answers feel hollow because Franklin does not do enough to bring the characters to life, or to make the plot(s) compelling or surprising.

It might be said that these disappointments are part of the point. That the novel is suggesting the mundane tragedy of daily failures to fulfil potential, as Smith’s dreamed-of life in New York simply seems to sag itself into a lame uselessness that undermines the hopes that come of being the Stanford-educated eldest son of an eminent Atlanta power couple. But this feels like a bit of a cop-out. And it certainly doesn’t excuse the over-reliance on sentences that walk a line between elegant and florid, of which far too many tip over into the dark realm of the latter, especially when Franklin seems to try and stick them at the end of almost every paragraph.

Ultimately, I am left with a different hope: that as this is the first debut novel of a successful poet to disappoint me, it ends up being the exception that proves the rule, and not the beginning of my disillusionment.

Click here to change your cookie preferences