At a museum recently, I caught myself focusing rather intently on a very specific spot on a statue of Zeus and thinking, “That’s… it?!” But the longer I stood there, the clearer it became that the ultimate alpha male of Greek mythology seemed impressively unbothered by his small “package”. Within seconds, my mind drifted inevitably to modern power men, especially those in politics.

A short walk through the sculptures of classical Greek reinforced the same realisation: Gods and heroes were depicted with muscular bodies but a remarkably modest physical attribute, a pattern that scholars have long explained. In that era, a small penis signalled discipline, rationality and self-control, though whether their poor wives were happy with that is another matter altogether. Exaggerated endowments, meanwhile, were reserved for satyrs, comedic figures and other avatars of chaos, always depicted with huge phalluses – lucky creatures in theory.

Because, as researchers like Alan McKee point out, size does matter in certain contexts. McKee, an Australian media scholar who studied cultural anxieties around penis size in his paper ‘Does Size Matter?’, notes that many men worry about their measurements and many women say it can make a difference in intimacy. But that is another conversation entirely. Biology has its rules, while modern politics has its own version of masculinity.

Macho politics thrives on loudness in contemporary Western democracies, and Cyprus is no exception. Here too, raised voices, thundering declarations and a parliament heavy with airborne testosterone often pass for leadership. Men perform strength, confuse aggression with authority and treat nuance as weakness.

In such a landscape, shouting passes for conviction and posturing for competence. A quick glance at international shirtless photo ops shows how eagerly some political wannabe alphas cling to theatrical masculinity when substance fails them.

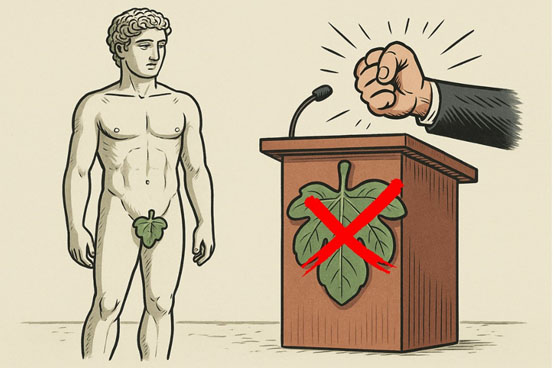

But this style of politics does not appear out of nowhere. It flourishes because it comfortably sits within a broader system that centres male authority and excuses its excesses as “strength”. This male-dominated order rewards dominance over competence and treats machismo as evidence of leadership. Cyprus, unsurprisingly, is also familiar with these rituals: the fist-on-the-table moments, the macho patriotic warnings and the testosterone-fuelled statements issued long before anything of substance is attempted.

And in such a system, it is hardly surprising that the only macho centimetres that actually matter – the ones inside the skull – remain tragically undervalued in modern leadership both abroad and at home. Strategic thinking is far scarcer than televised bravado, a pattern scholars call political masculinity, where performance is mistaken for authority and the phallus becomes shorthand for power.

Across cultures and eras, symbols of power have shifted, and the phallus has often been one of their central markers. Psychoanalytic theory likewise treats it as symbolic rather than biological, a reminder that phallic power is, in the end, imaginary – a performance we mistake for authority. In politics, that symbolism often appears in leaders who are more performative than confident, acting out a power they were never meant to possess.

Against this current backdrop of performative masculinity, the alpha-male leaders of antiquity look unexpectedly topical. Perhaps that is why the statues, with their famously small ‘anatomy’, still draw our gaze. Their calm presence reminds us that masculinity was not always a spectacle of competition and that power was not always performed at full volume. However, for anxious macho modern men in Cypriot public life, still unsure whether they meet society’s unspoken standards, there is always one convenient escape: claiming that their centimetres are rooted in the ancient Greek ideal.

Alas, we still move within the quiet logic of penis politics, a system in which egos expand as ideas contract. The statues have already issued their verdict. What remains to be seen is whether our male politicians can step beyond the phallocratic ideals they have built around themselves – size very much included.

Click here to change your cookie preferences