They were planning to put on a play written by an artificial intelligence programme in Prague this month, to mark the invention of robots (or at least the idea of robots) in the same city exactly one hundred years ago. Covid-19 got in the way of that, and it will now only be available free online late next month. Kind of symbolic, really: the future is quite different than they expected.

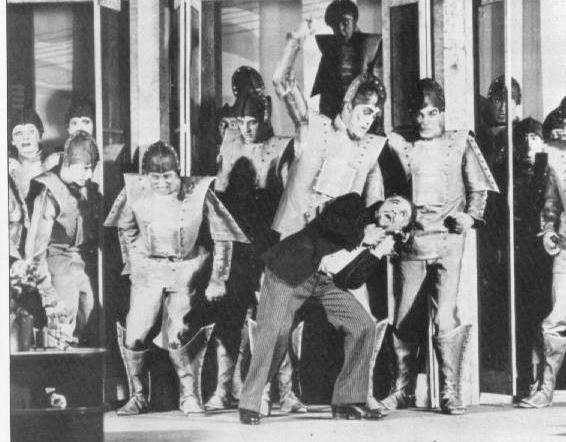

Karel Čapek’s play, ‘Rossum’s Universal Robots (RUR)’, was an instant hit in 1921. The imaginary ‘robots’ (a Czech word meaning serfs or slave labourers) were developed to spare human beings hard work on assembly lines and death on battlefields, but in the end they rebelled and wiped out the human race.

The play was on Broadway by 1922, starring a young Spencer Tracy, and it was in London’s West End the following year. By 1938 it was the first science-fiction drama ever broadcast on TV, live on the BBC.

Whereas in the real world of a century later, robots still can’t even dance. The Čapek brothers’ vision (it was Josef who came up with the name) hasn’t come true except in the movies.

It was the humanoid fallacy. In more recent movies human-seeming robots are even tragic figures, like Arnold Schwarzenegger’s version of the ‘Terminator’, or Roy Batty, the android anti-hero of ‘Blade Runner’, reminiscing sadly as he dies…

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

Great stuff, but robot arms and self-driving vehicles don’t talk like that. Those are the real robots, and generally they don’t talk at all. And obviously they don’t wipe out the human race. Just the jobs.

Automation 1.0 replaced most of the workers on assembly lines with machines that didn’t make Monday-morning mistakes, didn’t join trade unions, didn’t even have to be paid. The factories are mostly still there, churning out goods, but the well-paid jobs are largely gone and the big industrial cities are decaying into ‘rust belts’.

Automation 2.0 is mostly online, and it’s focussed on retail. The department stores were mostly gone even before Covid and the smaller shops are going now, swallowed up by Amazon and its many smaller rivals.

At least this time some new jobs are being created as well: minimum-wage, zero-hours jobs, mostly in warehouses, distribution centres and delivery services. The proportion of the population who are classed as ‘working poor’ is growing in every developed countries, with political radicalisation the predictable result, so far mostly to the right.

Automation 3.0 is almost here, and the new targets this time will be managerial and professional jobs – not all of them, of course, but whole layers of middle management in business and lesser-skilled positions in medicine, law, accountancy and allied trades. Killer algorithms are rampaging through the community, and there’s not a Robocop in sight.

In fact, this pattern is familiar to those who study the history of the original industrial revolution in England. The goods – shoes, tools, woven and knitted clothing – that were produced by independent and skilled craftsmen and women with reasonable incomes in 1750 were being made in factories by low-skilled wage slaves with almost no bargaining power by 1850.

Three generations after that trade unions and the welfare state began to narrow the yawning gap between the rich and the rest again, and the latter half of the 20th century was the best time in a long time for ordinary people in most places. Now the human skills are once more being usurped by the machines and the gaps are opening up again.

We are not doomed to simply recapitulate the past. Knowing what worked and what didn’t last time could help us to avoid the worst outcomes this time. That’s why we are hearing a lot about ‘basic income’ and expansions of the welfare state to ease the transition this time. But there’s not much actually happening – and we’re not even at ‘true’ AI yet.

We call anything that can do ‘machine-learning’ AI, but so far it’s just creating pseudo-cognitive skills in single quite narrow domains. The kind of broad-spectrum intelligence human beings have (or even dolphins, chimpanzees and crows) is not yet available in any machine, nor is the ‘Singularity’ about to sweep us all away into irrelevance next week.

Real AI will arrive in some form in the not-too-distant future, but predicting its social and political impact is hard. As hard as it would have been for the Čapek brothers and their audience to foresee in 1921 what robotics would really mean for people in 2021.

Gwynne Dyer’s new book is ‘Growing Pains: The Future of Democracy (and Work)’

Click here to change your cookie preferences