The latest of many plans for the peninsula would protect a tiny part of it but with visitor access made all-too-easy, and development sprouting up all over the rest of this precious area

I stopped the car. I had to get a better look. It was a long row of two-foot-tall metal posts, painted a dull brown. The row of closely spaced posts extended along one side of the dirt track that runs along the back of Toxeftra beach. Amazing. Wonderful.

It was, to the best of my recollection, the first tangible, targeted and (potentially) effective habitat protection I had seen on the Akamas peninsula for many a year. Ok, so one of the posts had already been knocked over, but I was not going to let that cloud my delight. The little posts, which I first saw this past January, were a wonder. A statement of intent from a state so chronically disinclined to state intent when it comes to protecting this wonderful corner of Cyprus. ‘You cannot drive on the foreshore and beach’ the little posts stated. Halleluiah.

The dune plants that once adorned the wide sandy stretch behind the turtle-nesting beach could now slowly return, no longer flattened by tyres. Plus the barriers represented added guarding for the turtle beach too, even if this so very important beach has long been strictly protected.

In fact, Toxeftra and Lara beaches, on the western Akamas coastline, are a conservation success story with little parallel elsewhere in Cyprus. But the same simply cannot be said for Akamas as a whole, even after all these long years of green effort and campaigning. I know you will have heard such cries before when it comes to Akamas, but right now really is ‘zero hour’ for this precious place.

For a while there though, I was able to bask in the joy of the little row of protecting posts, before reality forced me to ‘zoom out’ to focus on the deeply worrying big picture of what the future holds for Akamas. (I think it is true to say, based on talking with many a veteran of the struggle, that there is a bit of ‘negative conditioning’ that afflicts all who have fought to protect Akamas, which perhaps explains my great joy at the sight of a row of little posts…).

What is so special about the Akamas peninsula is that it can still be described as ‘wild’. A rare corner of Cyprus where a sizeable coastal area remains untouched by tarmac roads and development. A place you can walk for hours through juniper scrub and where you can still find a deserted cove. Where the colourful local characters you meet are not mildly inebriated tourists but rather free-roaming, grizzly Akamas goats. Where a flock of migrating herons or egrets can rest in peace by the sea.

No one can really dispute the unique importance of the peninsula in terms of landscape and nature: varied and rare habitats shaped by those characterful goats, nesting beaches for Green and Loggerhead turtles, amazing plant-life (much of it found only in Cyprus or only on the peninsula), migrant and breeding birds in varied abundance. And so much history too; so much man-made character, including in the surviving local communities.

Everyone, from politicians to developers to local communities and environmentalists, always line up to extol the virtues of the area (much as I have just done!). Yet agreement on a formula for protecting the Akamas while allowing sustainable economic development remains as elusive as ever. Plans and designs come and go, and nothing much happens; the area remains in limbo.

Bad news for the locals and bad news for the local environment, which cries out for sympathetic management. For the Akamas has always been a managed landscape, with farming and grazing key among the uses that have shaped what we know and love today. Fencing it off, even if it were possible, would in no way be desirable. Low-intensity farming and grazing need to continue, maintaining a rich landscape mosaic and reducing fire risk.

More modern-day uses such as tourism do not get the management they need either. Unmanaged tourism has a growing impact on the conservation status of the area. The roaming quad bikes and the dust and disturbance they bring with them are the most obvious – and galling – example of this.

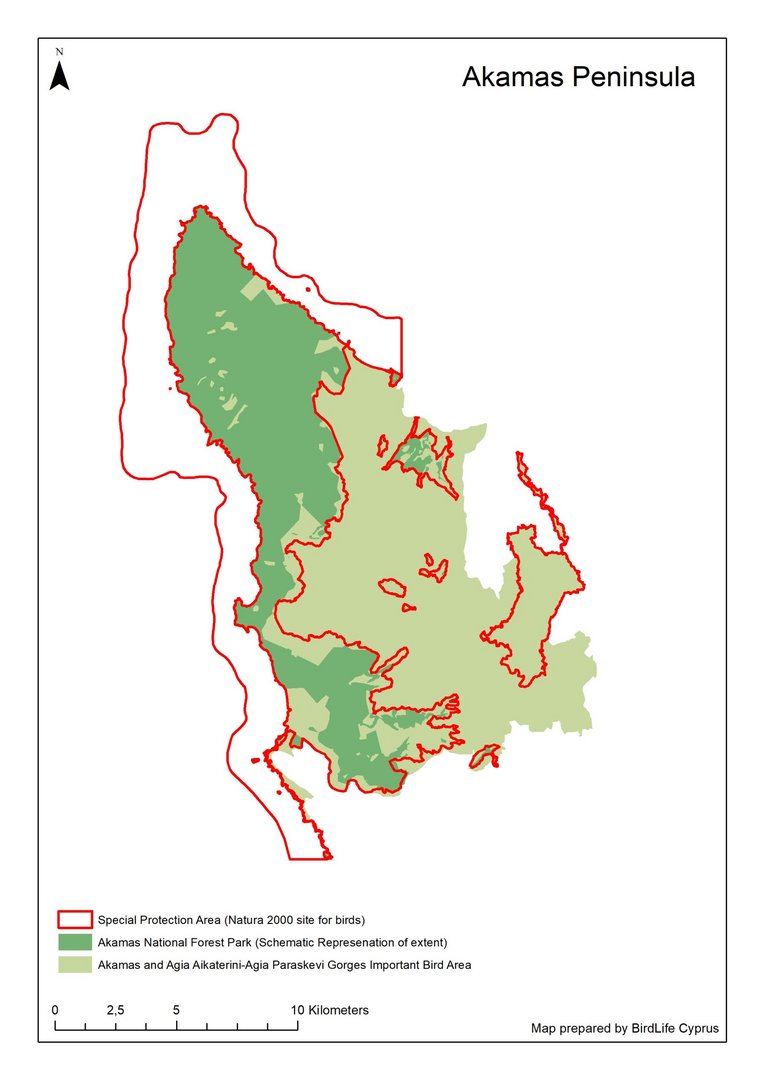

Based on scientific, ecological criteria recognised across the EU, the Akamas area enjoying the protection of Natura 2000 status should follow the boundaries of the Akamas Important Bird Area (IBA), which includes the entire peninsula plus the Laona plateau with its villages. The IBA covers the habitat that the eagles, rollers, migrating herons and other key birds of Akamas need, an excellent baseline for what should be kept safe.

However, the area Cyprus has designated as Akamas Natura 2000 is much smaller. It is also broken up into a series of hard-to-manage satellite protected ‘islands’. Management plans drawn up for this reduced Natura 2000 area have never made it off the pages and onto the ground. To add insult to the injury of inadequate designation, the state is now pushing ahead with implementation of a management plan for a sub-section of the designated Natura 2000 site: the Akamas State Forest area.

The row of new protecting posts at Toxeftra is part of the State Forest management effort, which is great. There is plenty else that is good in the forest management plan, such as targets for limiting visitor numbers. There are, however, dire risks in there too: road ‘improvements’ (including with tarmac) and visitor facilities sited deep in the Akamas heartland. How will these help keep Akamas wild?

And the real bugbear is this: new planning proposals, covering all of Akamas outside the narrow State Forest area, make room for an ‘alternative’ development in the form of ‘visitor farmsteads’. These farmsteads can include accommodation for up to 16 people, shops and entertainment. A fancy, rustic-sounding name for a Trojan horse opening the gates for development across most of the Akamas. Combined, the improved roads, visitor facilities and ‘visitor farmsteads’ spell the end of Akamas as an untouched area.

Yet the sustainable alternative is easy to see (and very much still worth fighting for). Dangerous tracks should be fixed where really necessary, but visitors should be drawn to the local villages, to find there their Akamas visitor passes, information, sustenance and post-visit meals and accommodation. This model would ensure visitors leave their cash in local communities.

Akamas is a big area by Cyprus standards, but a small one compared to protected wild areas elsewhere. It is nowhere near big enough to survive the impact of visitor kiosks, surfaced roads and ‘visitor farmsteads’ and still retain any essence of the wild, the element that makes Akamas special.

Martin Hellicar works as director of local nature conservation NGO BirdLife Cyprus. A PhD ecologist and former journalist, he is fortunate enough to work for an organisation whose positions closely match his, though the opinions expressed here are entirely his own…

Click here to change your cookie preferences