“You can’t talk about ESG and invest in a really bad actor – and more and more companies are afraid of the reputational risk,” warns one fund manager.

When Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko intensified his crackdown on protesters in February, activists turned their attention to one of the country’s sources of funds: international bond markets.

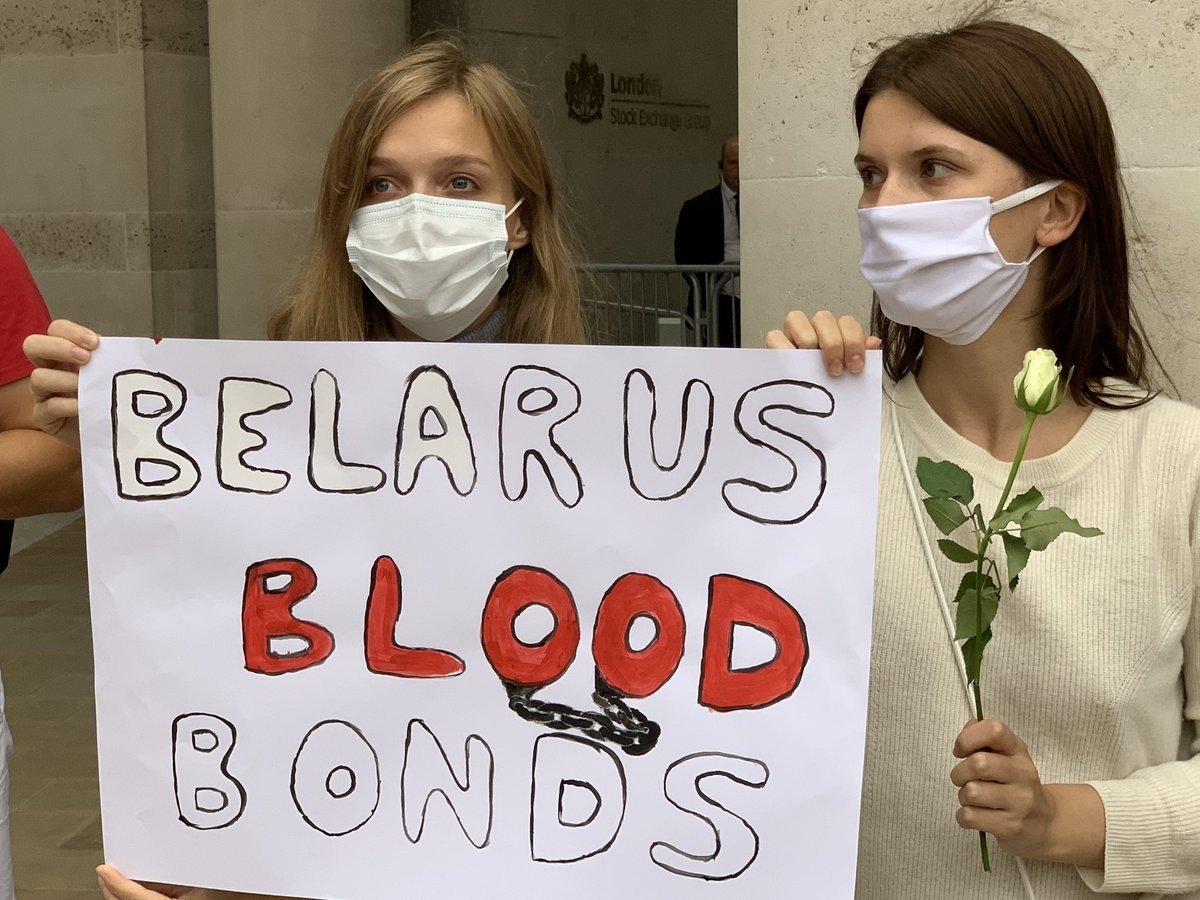

Hashtag #BelarusBloodBonds – which had first emerged around the country’s disputed 2020 elections – gathered steam again on Twitter, targeting big banks and funds, reminding them of their sustainable investment pledges and calling on them to shun Minsk’s debt.

One portfolio manager at a major global asset management company which had bought into Belarus’ most recent bond in June 2020, said their clients saw the social media chatter in February and pressed them to sell.

The manager, who requested anonymity, said, at the time their fund – having come to the conclusion that Lukashenko’s regime had taken a turn for the worse on human rights – was already in the process of selling.

Belarus has some $5.5 billion in hard-currency bonds outstanding, and counts fund managers, including BlackRock (BLK.N), PIMCO, NN IP, UBS (UBSG.S), Aberdeen Standard and JPMorgan

BlackRock, PIMCO, NN IP and JPMorgan declined to comment for this story.

“At a very minimum, we are linked to action of states through our investments in these bonds, because we are providing them with capital,” he said.

ESG is the buzzword these days, with hundreds of billions of dollars of investment chasing sustainable assets. In the world of sovereign debt, however, how a country’s record on human rights is handled is a grey area.

Some of the world’s largest asset managers remain heavily invested in regimes with questionable rights records.

The 2018 killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi did little to dampen the kingdom’s investor allure. China debt markets have sucked in billions despite European and U.S. criticism over alleged human rights abuses, denied by Beijing.

“The extreme description of these kind of assets is that these are blood bonds where the regime oppresses or tortures its citizens,” said Aberdeen Standard Investments’ portfolio manager Viktor Szabo, whose company holds Belarus bonds and has been targeted by the social media campaign.

“The question is where the threshold is, and that is all qualitative.”

Within days of the issue, protests against Lukashenko swelled, sparking an increasingly harsh response from authorities ahead of the August 9 elections.

Hard-currency sovereign bonds make up nearly a third of Belarus’ $18.5 external debt burden. But Lukashenko has increasingly relied on long-time ally, Russia for funding.

This Russian backstop and Belarus’s low debt-to-GDP ratios could also mean any new sanctions would pack less of a punch.

Russia is moving ahead with a second $500 million loan tranche for Belarus and has pledged more financial support in case of EU curbs.

“EU leaders will decide on sanctions so we will see what they do in the end,” Kaune said, pointing to both the Russia-style option of bans on buying new bonds, or the more extreme Venezuela-style option of a bond trading ban.

Once the extent of sanctions are known, “we will have to reassess whether access to those markets is something we want to have,” Kaune added.

Click here to change your cookie preferences