In a veteran war correspondent, THEO PANAYIDES finds a man capable of being precise and meticulous in the midst of chaos, aware of how quickly it can all go wrong

The house, in a quiet residential part of Nicosia, is “falling to pieces,” admits Jim Muir affably; there’s scaffolding outside the front door. The inside is cluttered, the balcony strewn with stray bits of board. Books line a couple of low shelves, a broad selection: William Blake, Nancy Mitford, Asimov, a journal called Palestinian Studies, a handful of National Geographics with their distinctive yellow spines. A giant poster of Saddam Hussein (the kind that must’ve been ubiquitous in 90s Iraq) adorns the corridor, torn into three pieces and reassembled; “I found him in Kirkuk,” explains Jim, at an army base taken over by the Kurds after Saddam’s fall. One room is entirely given over to piles of photos and old notebooks, which he’s in the process of sorting. Is he planning to write his memoirs? He shrugs, as if to say ‘Isn’t that what war correspondents always do?’.

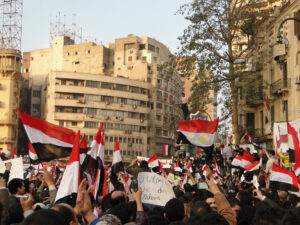

He’s been renting this house since the 90s, but the work was never in Cyprus; it was in Lebanon, later in Iraq and Afghanistan, later still in Syria, seeing war up close – it was usually war, though he covered the Arab Spring too – in the most war-torn region on the planet during the course of 40 years as a journalist and correspondent (he was freelance for 20 years, then joined the BBC in 1995). One might say he’s semi-retired – though he hates that word – these days, a few weeks from his 74th birthday, though he still writes “bits and pieces” and occasional features, shuttling between increasingly beleaguered Beirut (where he’s lived, on and off, since the mid-70s) and the rather dishevelled house in Nicosia.

He too seems a bit dishevelled, on first impression, with his thin white beard and worn white T-shirt, serving my espresso in an eggcup because the cups have gone missing (he also brings a plate of Medjool dates, in the Arab style) – but in fact that’s deceptive. He does have a rather distracted air, like a genial academic, but his conversation is precise and meticulous. He spells out names and places, to prevent inaccuracies. He shows me a page from the notebooks and I marvel at the neat, careful writing. I ask about hobbies and he mentions – of all things – birdwatching, which he’s done since childhood; a solitary, very orderly hobby. (A journalist is also an observer, like a birdwatcher.) Jim wields precision like a scalpel – and indeed like a shield, a way of distancing himself from the awful things we talk about. “His right foot was blown off complete – no, his left foot was blown off completely, and his right leg was just hanging by a piece of the flesh at the thigh,” he recalls, as if correctly ascertaining which foot it was could somehow lessen the horror of the scene.

Jim’s damaged bedroom

The luckless man in that story was Kaveh Golestan, Jim’s cameraman and close friend, who lost his life near the village of Kifri in April 2003. “That was the worst day of my life, professional or otherwise,” he says, “the last day of [Kaveh’s] and probably the worst of Stuart’s, because he eventually had to have an amputation halfway up the leg.” ‘Stuart’ was BBC producer Stuart Hughes, who accidentally stepped on a landmine as the crew got out of their car, having unwittingly been led into a minefield by their Peshmerga (Kurdish) guide. The mine exploded, shearing his foot in half – but the others, hearing the explosion, thought they were being shelled (it had happened before) so “Kaveh jumped out and ran down the hill, not realising he was running into a minefield. He stepped on one mine, fell on another – two more explosions. All in the space of about two seconds, this whole story”.

It’s an awful story, for all kinds of reasons – including what it says about how quickly and randomly it can all go wrong. Two seconds, a momentary lapse, was enough to destroy a man’s life, and indeed a man with years of experience in staying alive (Kaveh’s “bullshitting” skills had probably saved their skin when they were captured by the Taliban two years earlier; that’s a story in itself) – and not even really in a war zone, two seconds on a day when Jim and his crew were actually hanging around “waiting for the American invasion”. It was Sizdah Bedar, he recalls, the 13th day of the Iranian New Year, a day when Iranians traditionally go on a picnic – so they’d actually stopped for a picnic en route to the Peshmerga, since the war hadn’t really started yet. “Kaveh was in a very philosophical kind of mood,” recalls his friend. “He said ‘I only feel I’m really myself when I’m in war’… He was living his dream, really.”

There’s a fitting epitaph: ‘I only feel I’m really myself when I’m in war’. It’s unclear if the same holds true for Jim Muir – though he’s always been “a bit adventurous,” as he puts it. He’s the second of four brothers, born in England to a Scottish family. He lost his dad at 14, while in boarding school in Yorkshire; his mother took the rest of the family back to Scotland (Dad had left them with crippling debts) but Jim’s school agreed to keep him on “out of charity, basically”. On the one hand, his life continued much as before (he went on to study Arabic at Cambridge); on the other, he became estranged from his family and felt very lonely when he visited them in Scotland, like the expat he later became – “so I started going on night walks and things like that, and doing stupid things like walking across the Forth Rail Bridge”. He also started hitchhiking – “a bit of escapism” – saving up money from odd jobs and wandering around Europe from the age of 16. Like he says, adventurous.

Not macho, though – or at least it doesn’t seem that way. Jim has his tales of narrow escapes and hairy moments, to be sure – but the trouble always seems to come from bad luck or bad intel, not from taking risks or being reckless. The swashbuckling Hemingway mould isn’t really for him; his personal style is mild, accessible, almost diffident. “I’m not terribly good at self-promotion and that kind of thing,” he notes at one point. The trick with interviewing ordinary people in the Middle East, he says later (apart from speaking Arabic, which has always stood him in good stead), is to try and exude an unthreatening, trustworthy air – and he even gives ‘exude’ a little spin (‘exuuude’) as he sometimes does with slightly fancy words, as if reflexively embarrassed to be speaking them. Has he never done anything reckless in the line of work? “Well, I mean going to war is reckless, isn’t it?” he replies, not unreasonably.

He also covered the Arab Spring

War, let’s be clear, is horrendous; “There’s no such thing as a nice war, or a clean war”. We talk a bit about Ukraine, and he’s too much of a veteran reporter not to question the black-and-white narrative – but that’s not to excuse the war, war is inexcusable. “I mean, barbarity comes out,” he sighs, offering a story by way of illustration. Back in 1976, near the start of his time in Lebanon – he arrived in January 1975, just before the outbreak of civil war – a Palestinian camp called Tel al-Zaatar was overrun by Phalangist (right-wing Christian) forces and there was a terrible massacre, all the more unequal in that Palestinian fighters had earlier been withdrawn from the camp, as part of a deal. “And I was shown around the camp the next day by a young student with a party called the NLP, and he seemed a very nice young guy – he was a student, had been studying in Italy and stuff – and he was showing me around.

“So I got out of my car – and I thought I was standing on some old rags, but I was standing on a human body that had just been crushed into the parking area”. At the entrance to the camp was “a body that was half on the pavement and half on the road, and it was just being crushed like a rat. Inside the camp there were old men who’d had their heads smashed like eggshells, pregnant women disembowelled…” On the way back, Jim crossed a bridge across the Beirut river and noticed that three bodies which he’d spotted on the way there – the bodies of young Palestinian men, shot during the withdrawal – were nowhere to be seen: “So I got out and looked over the parapet – and there I saw a sight that I never wish anybody to see. Local butchers had been throwing their offal off this bridge, but bodies had also been thrown across – so you had piles of rotting offal but with human limbs, and heads and things, sticking out of it. And these young men had just been thrown over there to rot, along with the offal”. And meanwhile the student – a perfectly nice young chap, studying in Italy – was showing him around, unfazed and un-horrified.

“War triggers a sort of animalistic – well, that’s unfair to animals, because they don’t do that,” he concludes grimly. “A switch gets thrown, and people do unimaginable things – which may haunt them later, I don’t know. I hope so.”

Is it human nature to do these things?

“Regrettably, I think so.” Everyone’s shocked by the spectre of war ‘in Europe’ at the moment, but Srebrenica wasn’t that long ago. “I saw people coming out of concentration camps – I did Bosnia for several years, in the early 90s – looking literally like skeletons. So I don’t think Europeans are any more inherently civilised than other people.”

How can he see such awful things, and not be traumatised?

“Because I guess you sort of objectify it,” he replies carefully. “I mean, your job is to tell the world about it.”

There’s a distance in what Jim does – a necessary distance, but perhaps it also fits his temperament. It’s quite telling that he’s “sociable, but up to a point”: he’ll go to a party for a couple of hours, then “my feet heat up”, as he puts it, and he’s overwhelmed by a burning need to run off into the night. (He and his girlfriend in the 70s had a signal: if Jim tugged at his right earlobe it meant ‘Get me out of here right now!’, and she’d make their excuses.) There’s a solitary introverted side, the birdwatcher side, the meticulous side – but he needs the buzz too, the adventurous side. He moved to Cyprus in 1980, fleeing Beirut after being placed on a Syrian hit list, “and I’ve had a footprint here ever since” – and he’s fond of the place, viewing it as a kind of oasis from the regional mayhem, got married here (he’s been married twice and has four kids, two sons from the first marriage and two daughters from the second), readily agrees that it’s “much less ridiculous than Lebanon”; but Beirut has “a lot of electricity in the air” – albeit not in the actual electrical sockets, at least these days – “whereas Cyprus has a slightly more – agricultural flavour and pace of life… So I used to get a bit depressed here, actually, coming back in the 80s” (he was going back and forth for a while), “because in Beirut you’d be living on adrenaline, and I used to say that in Cyprus all the adrenaline would fit into a small bottle.”

What drives a war correspondent? The buzz, obviously. Maybe a certain gambler’s glee at the randomness of everything (Jim’s bedroom was hit by an Israeli naval shell around 7.30 one morning, during the siege of Beirut; just as well he’d gotten up early that day). Maybe some weird inner calculus that gets a kick from remaining precise and meticulous, even in the midst of chaos. But there must be something more.

What makes him do it? His faith in human nature, after all, was severely tested by the work (he’s notably pessimistic about climate change); family life was blighted by it. “I remember Shona my older daughter, when she was about three or four, when I’d be going off she’d literally cling to my leg,” he admits with an uncomfortable chuckle. “But I did feel that I had a sort of calling, you know? I felt a sort of duty. Compulsion, almost… I just felt I had to be there and witness things and tell the story, tell the world what was going on.” He recalls his friend and colleague Marie Colvin reading in the paper about Syria, and literally slamming her fist down on Jim’s kitchen table: “Terrible things are happening. We have to be there.” Marie Colvin was killed in Homs in 2012.

Jim Muir’s own politics are very BBC: “Liberal-left-ish,” he offers. “I’m not an ideologue.” Yet there is an ideology there, a near-religious zeal to witness and testify, a need to make sense of senseless war – and to help, if possible. Journalists can be vultures, extracting the story and moving on – but you also get “the occasional test,” he tells me, sharing one last memory. In 1977 there was a protest outside the Egyptian embassy in Beirut; shots were fired, people were fleeing. A guy on crutches tried to run away, but fell over – and Jim surprised himself by being reckless for once, running to the man amid a hail of bullets and helping him to safety. Sometimes “you’d despise yourself if you didn’t do the right thing,” he notes with a shrug. One for the memoirs, obviously.

Click here to change your cookie preferences