The first novel by a Turkish Cypriot author reflects a time on the island when there was sense of peace even though trouble was brewing

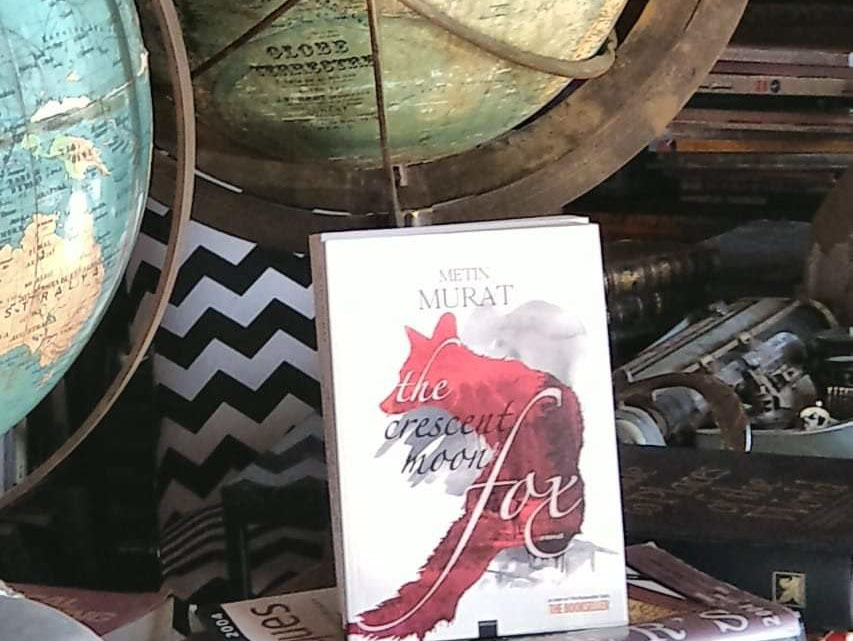

Bamyakoy, a fictional Cypriot village and its tough Turkish Cypriot inhabitants are the subject of the debut novel The Crescent Moon Fox by Metin Murat and just published by the Armida Publishing House.

Dedicated to “all Cypriots, irrespective of ethnicity, religion and political affiliation”, the book owes its inspiration to Murat’s PhD thesis at Aberystwyth University. It tells the story of Zeki, a Turkish Cypriot boy and his educational journey from Cyprus, then a British colony, to the UK and then back to the newly established Republic of Cyprus.

“The book is written for three different audiences — Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots and international,” says Murat, himself a successful British-born businessman now based in France.

“My PhD was in creative writing and actually consisted of two components. One was to create a work of fiction about Turkish Cypriots. The other was to examine colonial literature and look at how Turkish Cypriots were described by others, i.e. by the British or Greek Cypriots… So, having started researching the subject, I realised how little there is about Turkish Cypriots there and how one-sided it is — how Lawrence Durrell was horrible towards us and how most Greek Cypriot writers ignored us.

“Writing this book then was something that followed naturally… keeping in mind the famous quote from Sheakspeare’s Merchant of Venice: ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ I felt it was important to convey our own humanity to the Greek Cypriots, I wanted them to see our pain. You see, I think, a lot of Greek Cypriots are really blocked when it comes to us. There is this wall between us that stops them from seeing us as humans, and I want to break down this wall through literature.Talking about the politics and history is not enough to accomplish this. We can talk for ever and it will never get us anywhere.”

Murat hastens to add that he also wrote his book “for my own people, because I wanted to celebrate them”, just as he wrote the book “for people who don’t know anything about us in order to make them see us and understand us better, and more importantly to realise that we are being something different.”

Metin Murat, his editor Kris Konnaris on the left and his Armida publisher Haris Ioannides on the right

Murat Akiner, his father, was one of the few Turkish Cypriot diplomats in the new Ministry of Foreign Affairs when the independent Republic of Cyprus stepped onto the international stage,and was born in Platanissos [Balalan] village, located at the beginning of the the Karpas penisula. Shirin Akiner, his half-Welsh, half-Bengali mother, was a renowned scholar of Central Asia and Belarus.

His parents met in Moscow where his father had been sent as a diplomat, from where the couple later left, arriving in Ankara in 1965. With his mother seven months pregnant, the couple, with other family members, were involved in a fatal traffic accident, which only Murat’s mother survived.

In the 1980s, Murat went to Turkey to look for his father’s grave only to discover that because at the time of his death his father “no longer had his salary” he and his relatives were all buried in one of Ankara’s pauper graves. “I could not find anything any more,” Murat said, acknowledgeing that “maybe now, with DNA tests available, the situation would be different but at the time that was it.”

Growing up fatherless in London, where his mother moved after the accident, was difficult for a dyslexic boy whose strange foreign name made him a target for other kids.

“My mother sent me to a French lycee. She felt I would feel better in an international environment. I think hers was the right decision when you consider how everything in an English school can be so categorised by the social class system.”

Being dyslexic, he had a horrible time at school, “always getting terrible grades.” He recalls how his teachers were “wretched” towards his mother. They could never figure out “if I was the stupidest student they ever had or the laziest,” and so they kept telling her he should have left school at 16 to “start working in a factory.”

Instead of giving up, a resolute Murat, backed by his mother, defied their predictions and persisted, going on to Aberystwyth University to read history and French. In doing so, he discovered that regardless of what his doubting teachers may have thought, the higher he rose on the educational ladder, the more he enjoyed the challenge and the easier he found it to prevail.

He cites “an amazing art history teacher” who taught him all about the Italian Renaissance and introduced him to the concept of the Medicis as the “original international business people”. The experience turned out to be “the best businees school I could have had”, he exclaims. “The understanding of modern accounting, correspondence banking, customer service – all of these I got from my art history lessons with this man.”

Several years later, when he took a postgraduate course in business studies at the London School of Economics (LSE), knowing that such a diploma would “give me a good brand”, he came to the conclusion that he had “learnt more from the history of the Medicis than at the LSE.”

For many years after graduating, Metin worked for a multi-national company. Then, in 2011, he established his own firm with extensive business links throughout the Gulf, the Levant and North Africa. But he always felt he wanted to do more.

“The one thing I was always good at was writing — I grew up reading a lot,” he admits. “And the time came when I decided to do an MA in literature at Lancaster University and then this PhD and that really triggered this book.”

Having listened to the story of Murat’s father, a talented young man from a very poor family who by dint of intelligence and hard work went all the way to gain a masters degree at New York’s Columbia University, I wonder aloud just how much of his novel is based on past reality and the stories he heard from his own Turkish Cypriot family when visiting them during summers in Platanissos. Murat firmly denies that his novel contains such an abundance of biographical details.

“Yes, part of Zeki’s story is somewhat loosely based on my father’s but most of the stories in the book are made up. Bamyakoy is not Balalan (Platanissos) even though its name is connected with the real story,” he allows laughingly.

“You know, when I was visited Cyprus I was staying with my father’s sister and always on the first day of my stay she would give me okra (bamya in Turkish) to eat. On the first day, it was delicious — also on the second and third. But after a week of it, day after day, one had had enough [a point he also makes in the novel]. However, the point is that I always visited during the okra season and they ate whatever they harvested.”

He pauses to reflect before conceding that while the characters in his book are fictional, they were inspired by and infused with some of the spirit of the people he encountered during those visits to Balalan.

He liked and admired the strength of the villagers. “They were tough guys, tough people. My uncle was a wrestler and the women in the village… my aunt, for example … were very strong. Western intellectuals think these Muslim rural women are weak but there was nothing weak about my aunt. There was no man in the village who wouldn’t give my aunt due respect.”

He remembers another story about how in her 80s his aunt used to complain that her 90-year-old husband, suffering from prostate and lung cancer, must have stopped loving her because he would make love to her only twice a week and not every day.

“She was at ease with her sexuality and she knew what she wanted. And she was the one who would do the family accounts, in charge of buying and selling the crops. She was illiterate but she could do maths in her head. These are the things that we Turkish Cypriots have to remember, that yes, we were poor at that time, but there were also good things in our community, this sense of peace that it is so difficult to find nowadays.”

And this is certainly one of the things this book offers to its reader, regardless of who he or she might be. Murat’s book is a thoughtful and loving assembly of fragments from a vanished world that live on to define our present existence while reminding us of the commonality that marks our rich and varied, sometimes painful, disparate cultural roots.

The Crescent Moon Fox by Metin Murat is available at Moufflon Bookshop in Nicosia

Click here to change your cookie preferences